The rise in the use of the term “resilience” seems to mirror the sense of an accelerating pace of change. So, what does it mean? And is the meaning evolving over time?

One sense of the meaning implies a physical ability to handle stresses and shocks without breaking or failing. Flexible, robust and strong are synonyms; and opposites are rigid, fragile, and weak.

So, digging a bit deeper we know that strong implies an ability to withstand extreme stress while resilient implies the ability to withstanding variable stress. And the opposite of resilient is brittle because something can be both strong and brittle.

This is called passive resilience because it is an inherent property and cannot easily be changed. A ball is designed to be resilient – it will bounce back – and this inherent in the material and the structure. The implication of this is that to improve passive resilience we would need to remove and to replace with something better suited to the range of expected variation.

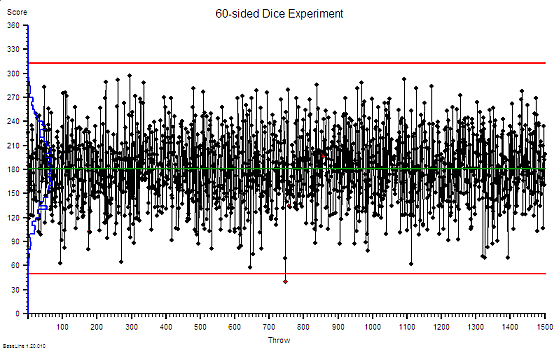

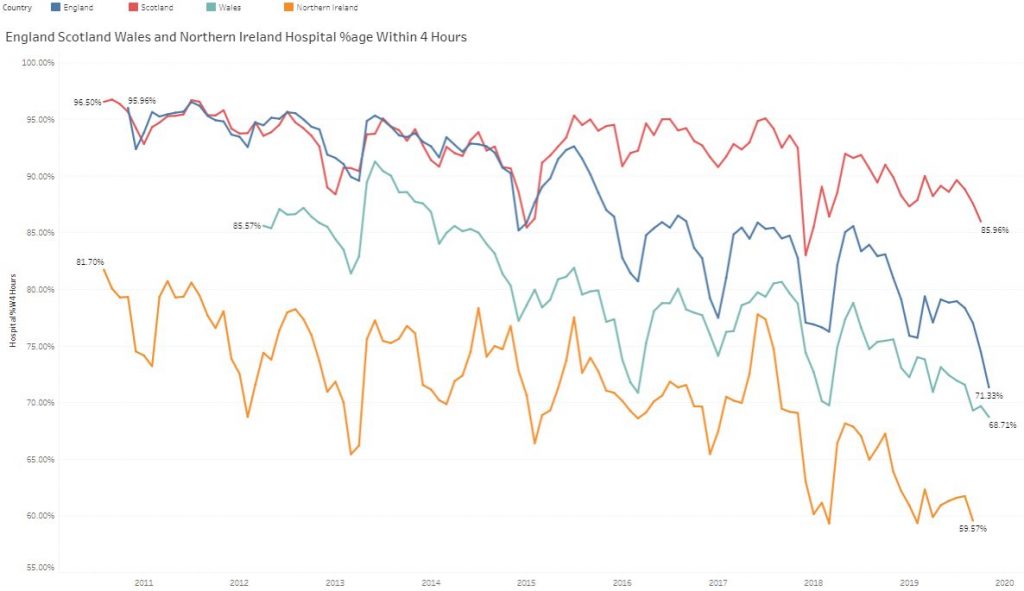

The concept of passive resilience applies to processes as well, and a common manifestation of a brittle process is one that has been designed using averages.

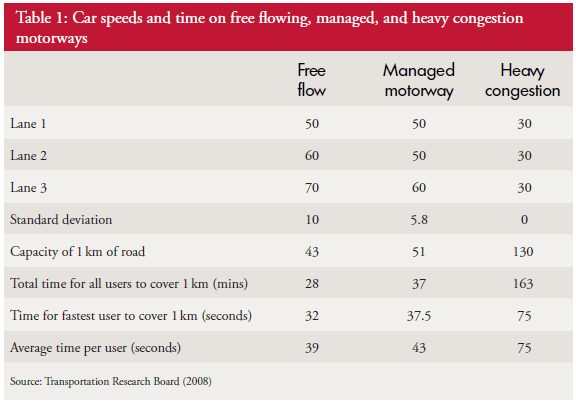

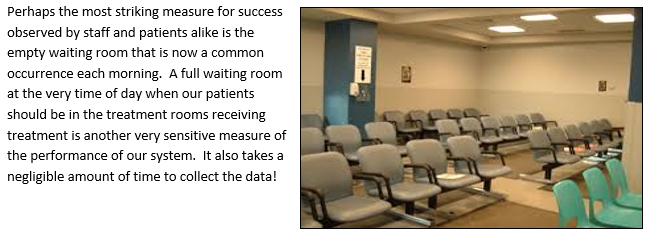

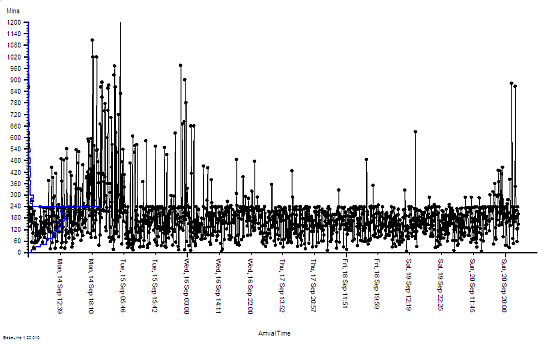

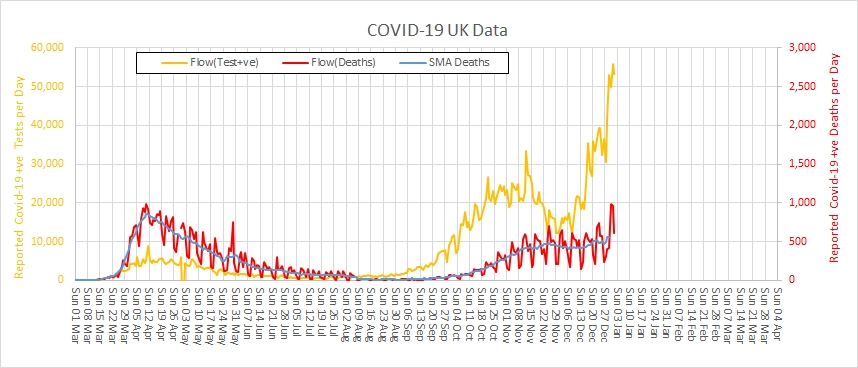

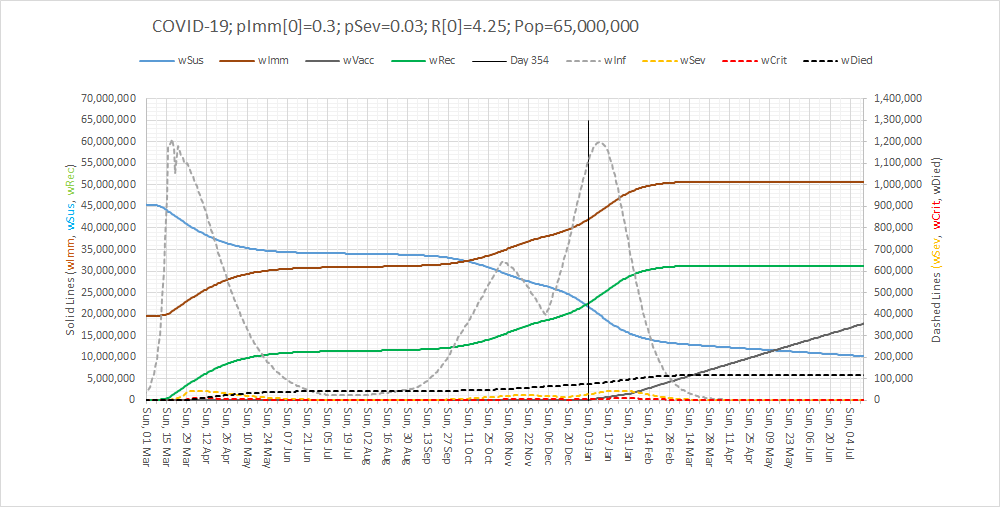

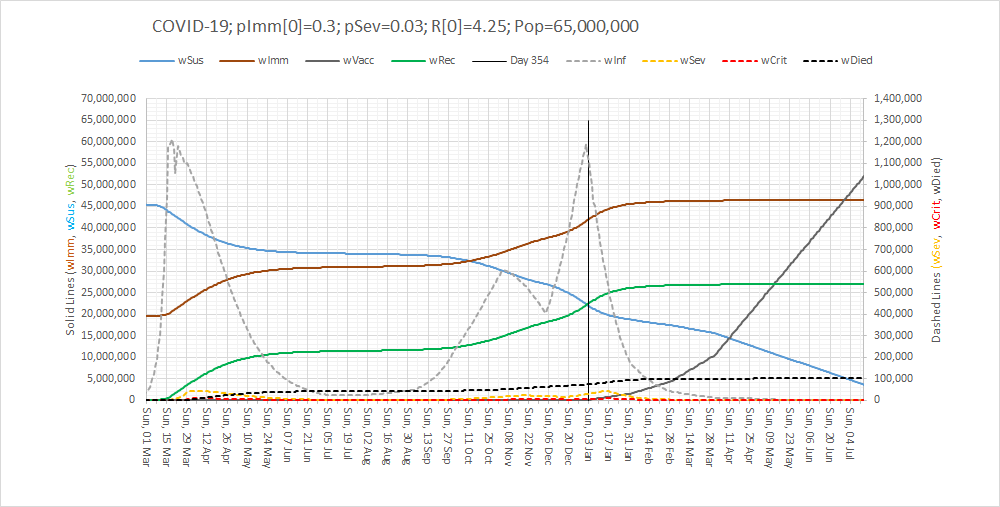

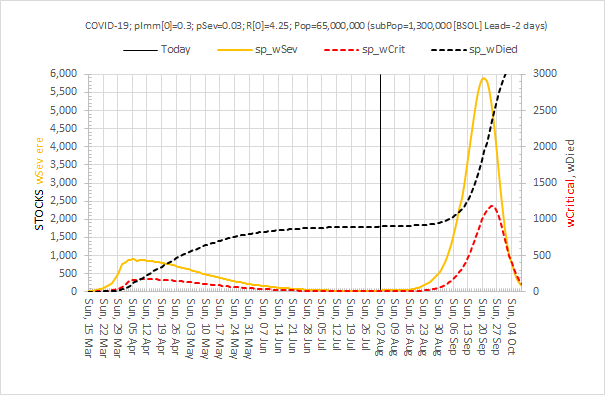

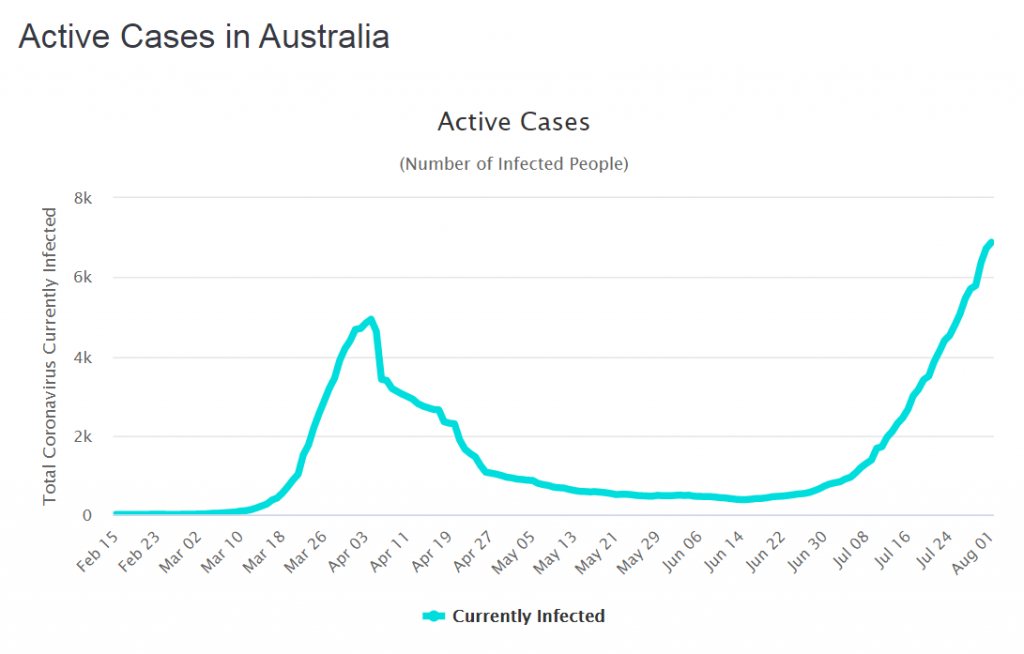

Processes imply flows. The flow into a process is called demand, while the flow out of the process is called activity. What goes in must come out, so if the demand exceeds the activity then a backlog will be growing inside the process. This growing queue creates a number of undesirable effects – first it takes up space, and second it increases the time for demand to be converted into activity. This conversion time is called the lead-time.

So, to avoid a growing queue and a growing wait, there must be sufficient flow-capacity at each and every step along the process. The obvious solution is to set the average flow-capacity equal to the average demand; and we do this because we know that more flow-capacity implies more cost – and to stay in business we must keep a lid on costs!

This sounds obvious and easy but does it actually work in practice?

The surprising answer is “No”. It doesn’t.

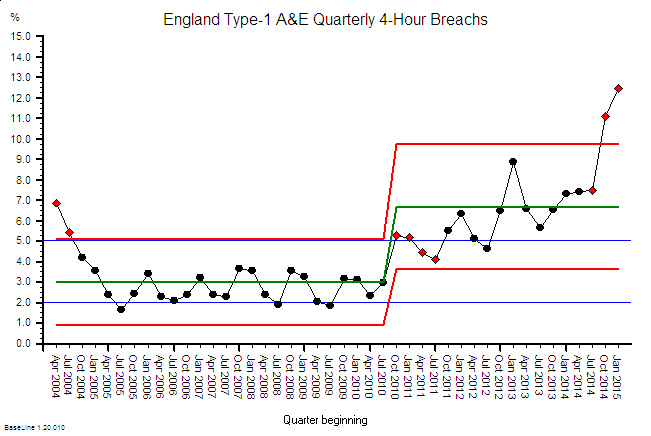

What happens in practice is that the measured average activity is always less than the funded flow-capacity, and so less than the demand. The backlogs will continue to grow; the lead-time will continue to grow; the waits will continue to grow; the internal congestion will continue to grow – until we run out of space. At that point everything can grind to a catastrophic halt. That is what we mean by a brittle process.

This fundamental and unexpected result can easily and quickly be demonstrated in a concrete way on a table top using ordinary dice and tokens. A credible game along these lines was described almost 40 years ago in The Goal by Eli Goldratt, originator of the school of improvement called Theory of Constraints. The emotional impact of gaining this insight can be profound and positive because it opens the door to a way forward which avoids the Flaw of Averages trap. There are countless success stories of using this understanding.

So, when we need to cope with variation and we choose a passive resilience approach then we have to plan to the extremes of the range of variation. Sometimes that is not possible and we are forced to accept the likelihood of failure. Or we can consider a different approach.

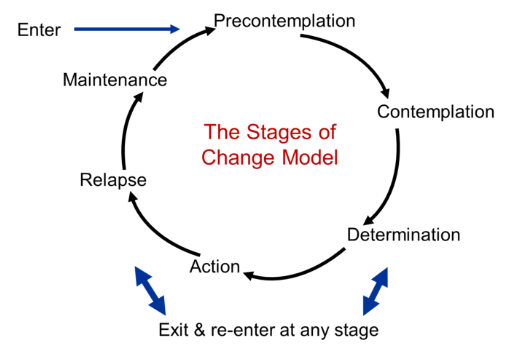

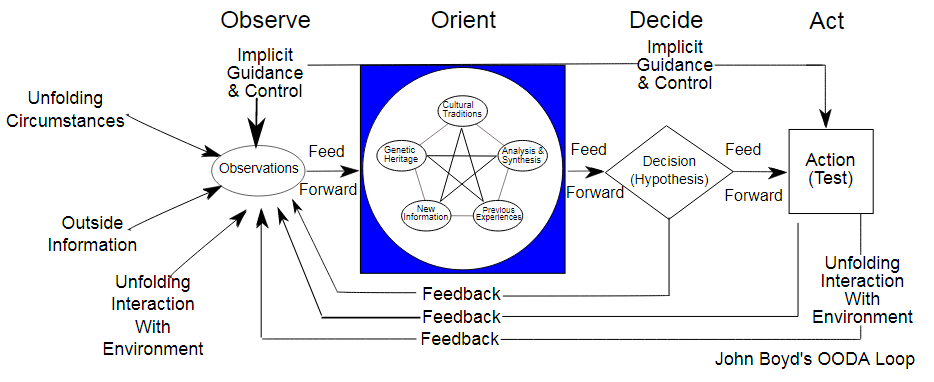

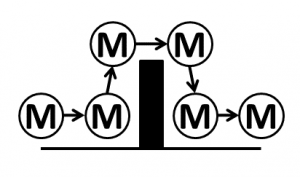

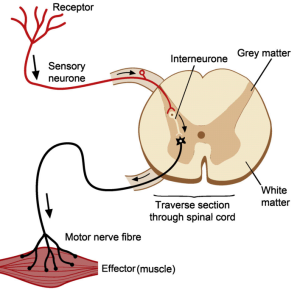

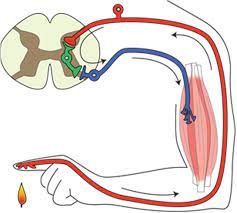

Reactive resilience is one that living systems have evolved to use extensively, and is illustrated by the simple reflex loop shown in the diagram.

A reactive system has three components linked together – a sensor (i.e. temperature sensitive nerves endings in the skin), a processor (i.e. the grey matter of the spinal chord) and an effector (i.e. the muscle, ligaments and bones). So, when a pre-defined limit of variation is reached (e.g. the flame) then the protective reaction withdraws the finger before it becomes damaged. The advantage this type of reactive resilience is that it is relatively simple and relatively fast. The disadvantage is that it is not addressing the cause of the problem.

This is called reactive, automatic and agnostic.

The automatic self-regulating systems that we see in biology, and that we have emulated in our machines, are evidence of the effectiveness of a combination of passive and reactive resilience. It is good enough for most scenarios – so long as the context remains stable. The problem comes when the context is evolving, and in that case the automatic/reflex/blind/agnostic approach will fail – at some point.

Survival in an evolving context requires more – it requires proactive resilience.

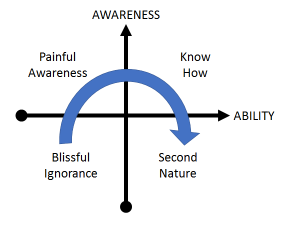

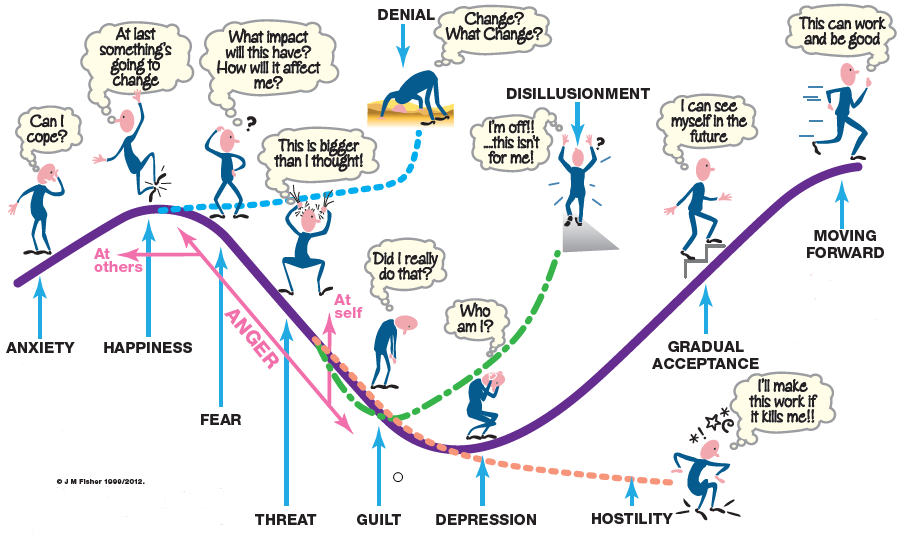

What that means is that the processor component of the feedback loop gains an extra feature – a memory. The advantage this brings is that past experience can be recalled, reflected upon and used to guide future expectation and future behaviour. We can listen and learn and become proactive. We can look ahead and we can keep up with our evolving context. One might call, this reactive adaptation or co-evolution and it is a widely observed phenomenon in nature.

The usual manifestation is this called competition.

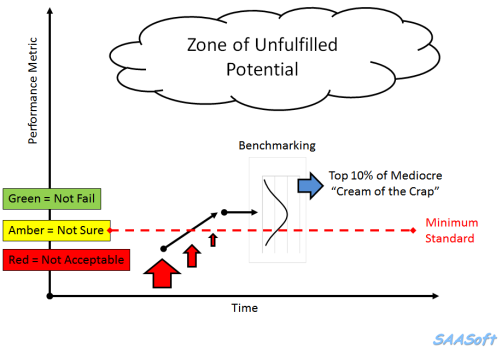

Those who can reactively adapt faster and more effectively than others have a better chance of not failing – i.e. a better chance of survival. The traditional term for this is survival of the fittest but the trendier term for proactive resilience is agile.

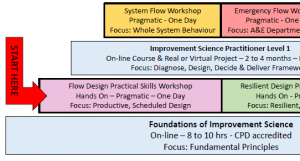

And that is what successful organisations are learning to do. They are adding a layer of proactive resilience on top of their reactive resilience and their passive resilience.

All three layers of resilience are required to survive in an evolving context.

One manifestation of this is the concept of design which is where we create things with the required resilience before they are needed. This is illustrated by the design squiggle which has time running left to right and shows the design evolving adaptively until there is sufficient clarity to implement and possibly automate.

And one interesting thing about design is that it can be done without an understanding of how something works – just knowing what works is enough. The elegant and durable medieval cathedrals were designed and built by Master builders who had no formal education. They learned the heuristics as apprentices and through experience.

And if we project the word game forwards we might anticipate a form of resilience called proactive adaptation. However, we sense that is a novel thing because there is no proadaptive word in the dictionary.

PS. We might also use the term Anti-Fragile, which is the name of a thought-provoking book that explores this very topic.

Abstract

Abstract