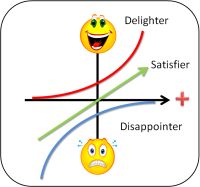

All improvement implies change – some may be incremental elimination of current Niggles; other may be breakthrough achievement of future NiceIfs.

All improvement implies change – some may be incremental elimination of current Niggles; other may be breakthrough achievement of future NiceIfs.

Change is an uphill struggle and the inevitable friction generates heat and sparks which dissipate some of the energy.

People throw spanners into the wheel which may eventually grind to a halt. Experts talk about “oiling the wheels of change” and generating momentum. The mechanical metaphors are numerous and have a common thread – that change requires pushing.

The unstated assumption is that resistance is “bad” and any means to overcome or bypass resistance is therefore justified – but this assumption is one-sided and discounts the possibility that there is a “good” side to resistance.

Suppose a design is proposed that would be effective (it would do the right thing) then resistance-to-change would be counter-improvement. Suppose the proposed design would be ineffective (it would not do the right thing and might even lead to the wrong thing) then resistance-to-change would be protective. The difference is the effectiveness of the design – not the presence of resistance-to-change.

Effectiveness has two components – effective in theory and effective in practice. Demonstrating effectiveness in theory is the purpose of pure research; delivering effectiveness in practice is the purpose of applied research. Both are embraced in Improvement Science.

Who is best placed to decide what will work in theory? An academic.

Who is best placed to decide what can work in practice? A pragmatist.

So we need both doing the parts that they do best. And we need them doing it at the same time … not in sequence … not theory and then practice.

It is a common assumption that novel designs are created sequentially – working from big conceptual chunks in stages of increasing detail to the final blueprints.

Reality is a bit messier than this!

An experienced design team will flip between broad-brush and fine-detail and they know the importance of including both theorists and pragmatists in the team. This is where the practical challenge comes because most people have a preference for one or the other modes of thinking.

Coordinating the effective-design-conversation requires awareness by everyone of the value of both. This is not discussion, instruction, manipulation, or facilitation – it is education. The role of the design team leader is to create the context to allow the learning to flow and the synergy to emerge.

The symptoms and signs associated with inexperienced design teams are:

- Design done behind closed doors by strategists with the assistance of theoretical advisors called management consultants.

- Design decisions are delivered as a “fait accompli” to those expected to “operationalise” them.

- Language such as “herding cats” is used to refer to the influential skeptics who represent the “front line barrier to change”.

These symptoms are harbingers of failure – poor designs that flounder on the Rocks of Don’t Do and good designs that get stuck on the Sands of Won’t Do.

The experienced design team knows these hidden dangers and has learned how to steer around them by demonstrating respect for the theory and for the practice and staying in the Channel to Success. There need to be respected Optics (visionary optimists) and credible Skeptics (respectful pessimists) at both the academic and the pragmatic poles to generate creative resonance. Synergy. An effective design team includes the role of Credible Skeptic.

And there are no chairs at the effective design table for the Politics (egocentric activists) and the Cynics (disrespectful pessimists). Their beliefs, attitudes and behaviours generate dissonance and turbulence which dissipates and wastes the effort, time and money of everyone else.

And we must always remember that effective design comes before efficient design. Doing the wrong thing efficiently makes it wronger! First do the right thing – then do it better. That is a design where everyone benefits.