I often hear the comments “I cannot see the wood for the trees”, “I am drowning in an ocean of data” and “I cannot identify the cause of the problem”. We have data, we know there is a problem and we sense there is a soluton; the gap seems to be using the data to find a solution to the problem.

Most quantitative data is presented as tables of columns and rows of numbers; and is indigestable by the majority of people. Numbers are a recent invention on a biological timescale and we have not yet evolved to effortlessly process data presented in that format. We are visual animals and we have evolved to be very good at seeing patterns in pictures – because it was critical to survival. Another recent invention is spoken language and, long before writing was invented, accumulated knowledge and wisdom was passed down by word of mouth as legends, myths and stories. Stories are general descriptions that suggest specific solutions. So why do we have such difficulty in extracting the story from the data? Perhaps it is because we use our ears to hear stories that are communicated in words and we use our eyes to see patterns in pictures. Presenting quantitative data as streams of printed symbols just doesn’t work as well. To see the story in the data we need to present it as a picture and then talk about what we perceive.

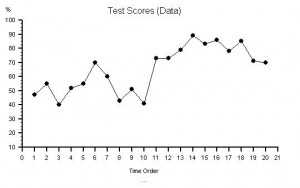

Here are some data – a series of numbers recorded over a period of time – what is the story?

47, 55, 40, 52, 55, 70, 60, 43, 51, 41, 73, 73, 79, 89, 83, 86, 78, 85, 71, 70

Here is the same data converted into a picture. You can see the message in the data … something changed between measurement 10 and 11. The chart does not tell us why it changed – it only tells us when it happened and sugegsts what to look for – anything that is capable of causing the effect we can see. We now have a story and our curiosity is aroused. We want an explanation; we want to understand; we want to learn; and we want to improve. (For source of data and image visit www.valuesystemdesign.com).

A picture can save a thousand words and ten thousand numbers!