About a year ago we looked back at the previous 10 years of NHS unscheduled care performance …

About a year ago we looked back at the previous 10 years of NHS unscheduled care performance …

… and warned that a catastrophe was on the way because we had unintentionally created a urgent care “pressure cooker”.

Did waving the red warning flag make any difference? It seems not.

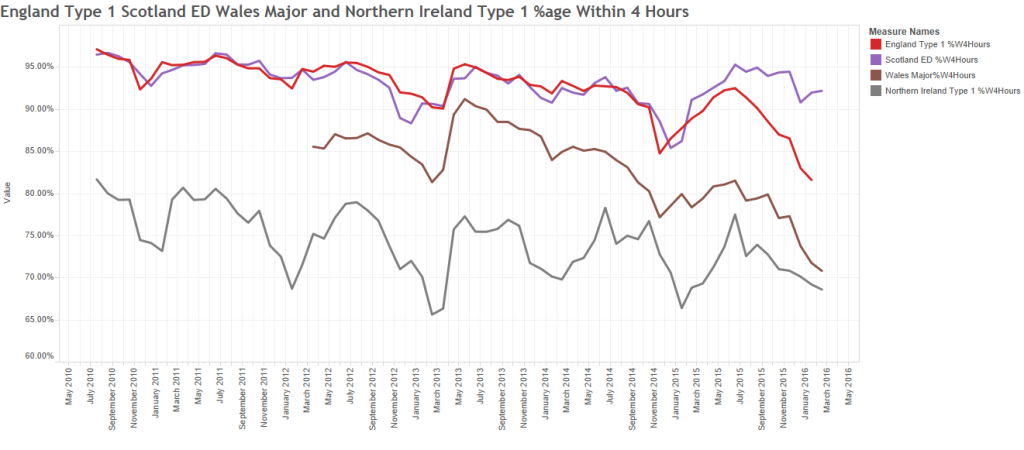

The catastrophe unfolded as predicted … A&E performance slumped to an all-time low, and has not recovered.

A pressure cooker is an elegantly simple self-regulating system. A strong metal box with a sealed lid and a pressure-sensitive valve. Food cooks more quickly at a higher temperature, and we can increase the boiling point of water by increasing the ambient pressure. So all we need to do is put some water in the cooker, close the lid, set the pressure limit we need (i.e. the temperature we want) and apply some heat. Simple. As the water boils the steam increases the pressure inside, until the regulator valve opens and lets a bit of steam out. The more heat we apply – the faster the steam comes out – but the internal pressure and temperature remain constant. An elegantly simple self-regulating system.

Our unscheduled care acute hospital “pressure cooker” design is very similar – but it has an additional feature – we can squeeze raw patients in through a one-way valve labelled “admissions”. The internal pressure will eventually squeeze them out through another one-way pressure-sensitive valve called “discharges”.

But there is not much head-space inside our hospital (i.e. empty beds) so pushing patients in will increase the pressure inside, and it will trigger an internal reaction called “fire-fighting” that generates heat (but no insight). When the internal pressure reaches the critical level, patients are squeezed out; ready-or-not.

What emerges from the chaotic internal cauldron is a mixture of under-cooked, just-right, and over-cooked patients. And we then conduct quality control audits and we label what we find as “quality variation”, but it looks random so it gives us no clues as to the causes or what to do next.

Equilibrium is eventually achieved – what goes in comes out – the pressure and temperature auto-regulate – the chaos becomes chronic – and the quality of the output is predictably unacceptable and unpredictable, with some of it randomly spoiled (i.e. harmed).

And our acute care pressure cooker is very resistant to external influences. It is one of its key design features, it is an auto-regulating system.

Option 1: Admissions Avoidance

Squeezing a bit less in does not make any difference to the internal pressure and temperature. It auto-regulates. The reduced inflow means a reduced outflow and a longer cooking time and we just get less under-cooked and more over-cooked output. Oh, and we go bust because our revenue has reduced but our costs have not.

Option 2: Build a Bigger Hospital

Building a bigger pressure cooker (i.e. adding more beds) does not make any sustained difference either. Again the system auto-regulates. The extra space-capacity allows a longer cooking time – and again we get less under-cooked and more over-cooked output. Oh, and we still go bust (same revenue but increased cost).

Option 3: Reduce the Expectation

Turning down the heat (i.e. reducing the 4 hr A&E lead time target yield from 98% to 95%) does not make any difference. Our elegant auto-regulating design adjusts itself to sustain the internal pressure and temperature. Output is still variable, but least we do not go bust.

This metaphor may go some way to explain why the intuitively obvious “initiatives” to improve unscheduled care performance appear to have had no significant or sustained impact.

And what is more worrying is that they may even have made the situation worse.

Also, working inside an urgent care pressure cooker is dangerous. People get emotionally damaged and permanently scarred.

The good news is that a different approach is available … a health and social care systems engineering (HSCSE) approach … one that we could use to change the fundamental design from fire-fighter to flow-facilitator.

Using HSCSE theory, techniques and tools we could specify, design, build, verify, implement and validate a low-pressure, low-resistance, low-wait, low-latency, high-efficiency unscheduled care flow design that is safe, timely, effective and affordable.

But we are not training NHS staff to do that.

Why is that? Is is because we are not aware that this is possible, or that we do not believe that it can work, or that we lack the capability to do it? Or all three?

The first step is raising awareness … so here is an example that proves it is possible.