![]() It had been some time since Bob and Leslie had chatted so an email from the blue was a welcome distraction from a complex data analysis task.

It had been some time since Bob and Leslie had chatted so an email from the blue was a welcome distraction from a complex data analysis task.

<Bob> Hi Leslie, great to hear from you. I was beginning to think you had lost interest in health care improvement-by-design.

<Leslie> Hi Bob, not at all. Rather the opposite. I’ve been very busy using everything that I’ve learned so far. It’s applications are endless, but I have hit a problem that I have been unable to solve, and it is driving me nuts!

<Bob> OK. That sounds encouraging and interesting. Would you be able to outline this thorny problem and I will help if I can.

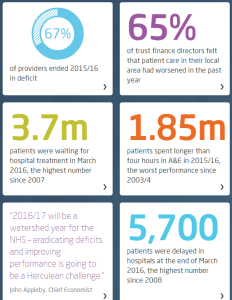

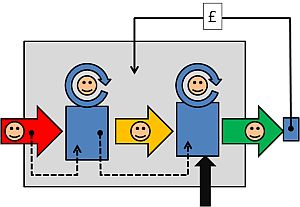

<Leslie> Thanks Bob. It relates to a big issue that my organisation is stuck with – managing urgent admissions. The problem is that very often there is no bed available, but there is no predictability to that. It feels like a lottery; a quality and safety lottery. The clinicians are clamoring for “more beds” but the commissioners are saying “there is no more money“. So the focus has turned to reducing length of stay.

<Bob> OK. A focus on length of stay sounds reasonable. Reducing that can free up enough beds to provide the necessary space-capacity resilience to dramatically improve the service quality. So long as you don’t then close all the “empty” beds to save money, or fall into the trap of believing that 85% average bed occupancy is the “optimum”.

<Leslie> Yes, I know. We have explored all of these topics before. That is not the problem.

<Bob> OK. What is the problem?

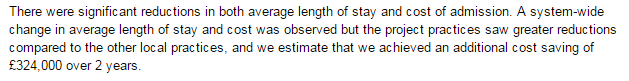

<Leslie> The problem is demonstrating objectively that the length-of-stay reduction experiments are having a beneficial impact. The data seems to say they they are, and the senior managers are trumpeting the success, but the people on the ground say they are not. We have hit a stalemate.

<Bob> Ah ha! That old chestnut. So, can I first ask what happens to the patients who cannot get a bed urgently?

<Leslie> Good question. We have mapped and measured that. What happens is the most urgent admission failures spill over to commercial service providers, who charge a fee-per-case and we have no choice but to pay it. The Director of Finance is going mental! The less urgent admission failures just wait on queue-in-the-community until a bed becomes available. They are the ones who are complaining the most, so the Director of Governance is also going mental. The Director of Operations is caught in the cross-fire and the Chief Executive and Chair are doing their best to calm frayed tempers and to referee the increasingly toxic arguments.

<Bob> OK. I can see why a “Reduce Length of Stay Initiative” would tick everyone’s Nice If box. So, the data analysts are saying “the length of stay has come down since the Initiative was launched” but the teams on the ground are saying “it feels the same to us … the beds are still full and we still cannot admit patients“.

<Leslie> Yes, that is exactly it. And everyone has come to the conclusion that demand must have increased so it is pointless to attempt to reduce length of stay because when we do that it just sucks in more work. They are feeling increasingly helpless and hopeless.

<Bob> OK. Well, the “chronic backlog of unmet need” issue is certainly possible, but your data will show if admissions have gone up.

<Leslie> I know, and as far as I can see they have not.

<Bob> OK. So I’m guessing that the next explanation is that “the data is wonky“.

<Leslie> Yup. Spot on. So, to counter that the Information Department has embarked on a massive push on data collection and quality control and they are adamant that the data is complete and clean.

<Bob> OK. So what is your diagnosis?

<Leslie> I don’t have one, that’s why I emailed you. I’m stuck.

<Bob> OK. We need a diagnosis, and that means we need to take a “history” and “examine” the process. Can you tell me the outline of the RLoS Initiative.

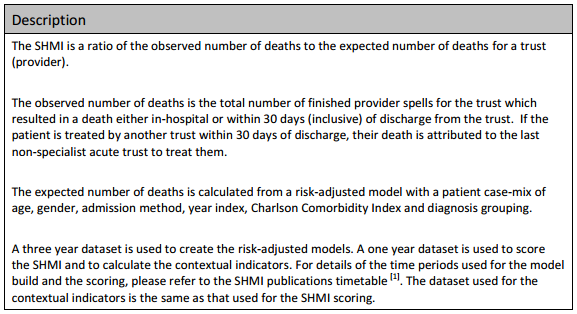

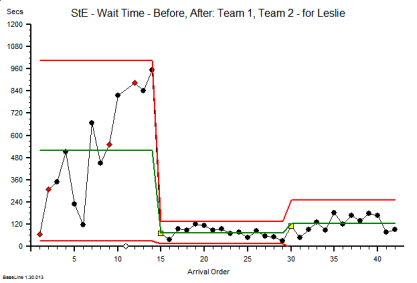

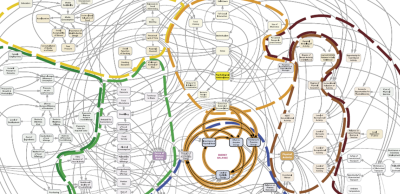

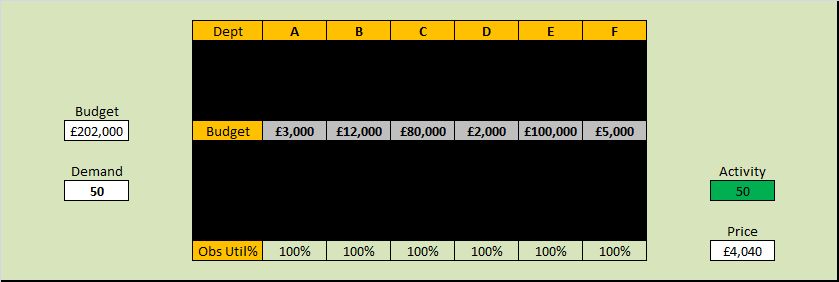

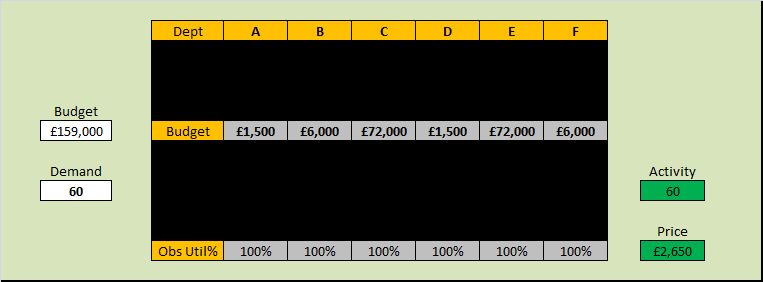

<Leslie> We knew that we would need a baseline to measure from so we got the historical admission and discharge data and plotted a Diagnostic Vitals Chart®. I have learned something from my HCSE training! Then we planned the implementation of a visual feedback tool that would show ward staff which patients were delayed so that they could focus on “unblocking” the bottlenecks. We then planned to measure the impact of the intervention for three months, and then we planned to compare the average length of stay before and after the RLoS Intervention with a big enough data set to give us an accurate estimate of the averages. The data showed a very obvious improvement, a highly statistically significant one.

<Bob> OK. It sounds like you have avoided the usual trap of just relying on subjective feedback, and now have a different problem because your objective and subjective feedback are in disagreement.

<Leslie> Yes. And I have to say, getting stuck like this has rather dented my confidence.

<Bob> Fear not Leslie. I said this is an “old chestnut” and I can say with 100% confidence that you already have what you need in your T4 kit bag?

<Leslie>Tee-Four?

<Bob> Sorry, a new abbreviation. It stands for “theory, techniques, tools and training“.

<Leslie> Phew! That is very reassuring to hear, but it does not tell me what to do next.

<Bob> You are an engineer now Leslie, so you need to don the hard-hat of Improvement-by-Design. Start with your Needs Analysis.

<Leslie> OK. I need a trustworthy tool that will tell me if the planned intervention has has a significant impact on length of stay, for better or worse or not at all. And I need it to tell me that quickly so I can decide what to do next.

<Bob> Good. Now list all the things that you currently have that you feel you can trust.

<Leslie> I do actually trust that the Information team collect, store, verify and clean the raw data – they are really passionate about it. And I do trust that the front line teams are giving accurate subjective feedback – I work with them and they are just as passionate. And I do trust the systems engineering “T4” kit bag – it has proven itself again-and-again.

<Bob> Good, and I say that because you have everything you need to solve this, and it sounds like the data analysis part of the process is a good place to focus.

<Leslie> That was my conclusion too. And I have looked at the process, and I can’t see a flaw. It is driving me nuts!

<Bob> OK. Let us take a different tack. Have you thought about designing the tool you need from scratch?

<Leslie> No. I’ve been using the ones I already have, and assume that I must be using them incorrectly, but I can’t see where I’m going wrong.

<Bob> Ah! Then, I think it would be a good idea to run each of your tools through a verification test and check that they are fit-4-purpose in this specific context.

<Leslie> OK. That sounds like something I haven’t covered before.

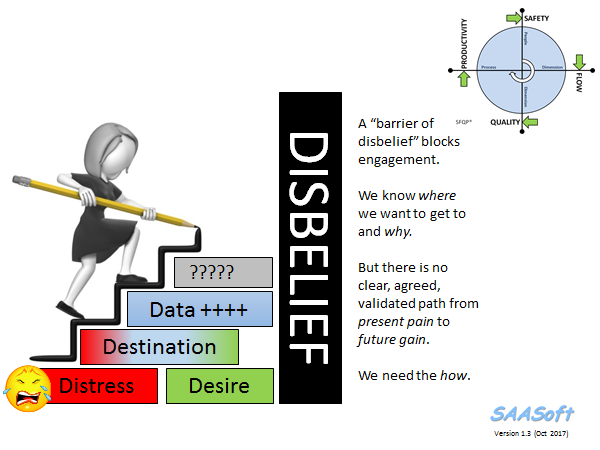

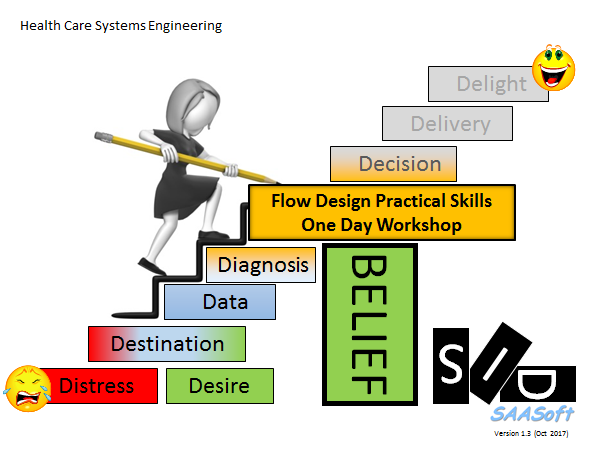

<Bob> I know. Designing verification test-rigs is part of the Level 2 training. I think you have demonstrated that you are ready to take the next step up the HCSE learning curve.

<Leslie> Do you mean I can learn how to design and build my own tools? Special tools for specific tasks?

<Bob> Yup. All the techniques and tools that you are using now had to be specified, designed, built, verified, and validated. That is why you can trust them to be fit-4-purpose.

<Leslie> Wooohooo! I knew it was a good idea to give you a call. Let’s get started.

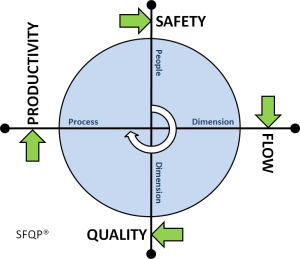

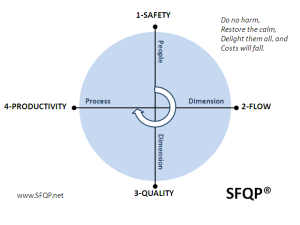

[Postscript] And Leslie, together with the other stakeholders, went on to design the tool that they needed and to use the available data to dissolve the stalemate. And once everyone was on the same page again they were able to work collaboratively to resolve the flow problems, and to improve the safety, flow, quality and affordability of their service. Oh, and to know for sure that they had improved it.