It is always rewarding when separate but related ideas come together and go “click”.

And this week I had one of those “ah ha” moments while attempting to explain how the process of engagement works.

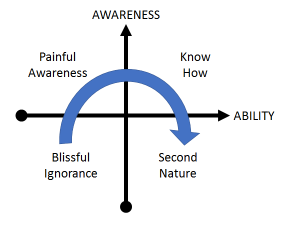

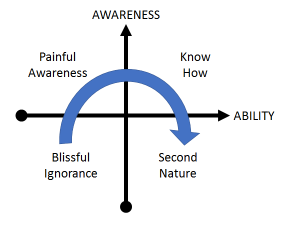

Many years ago I was introduced to the conscious-competence model of learning which I found really insightful. Sometime later I renamed it as the awareness-ability model because the term “incompetent” felt too judgemental.

The idea is that when we learn, we all start from a position of being unaware of our inability. We don’t know what we don’t know.

The idea is that when we learn, we all start from a position of being unaware of our inability. We don’t know what we don’t know.

This state is called blissful ignorance.

And it is only when we try to do something that we become aware of what we cannot do; which can lead to temper tantrums!

As we ask, listen, reflect, learn, and practice our ability improves and we enter the zone of Know How. We become able to demonstrate what we can do, and explain how we are doing it.

The Zone of Known Known.

The final phase comes when our ability becomes so habitual that we forget how we achieve our skill – it has become so intuitive and second nature.

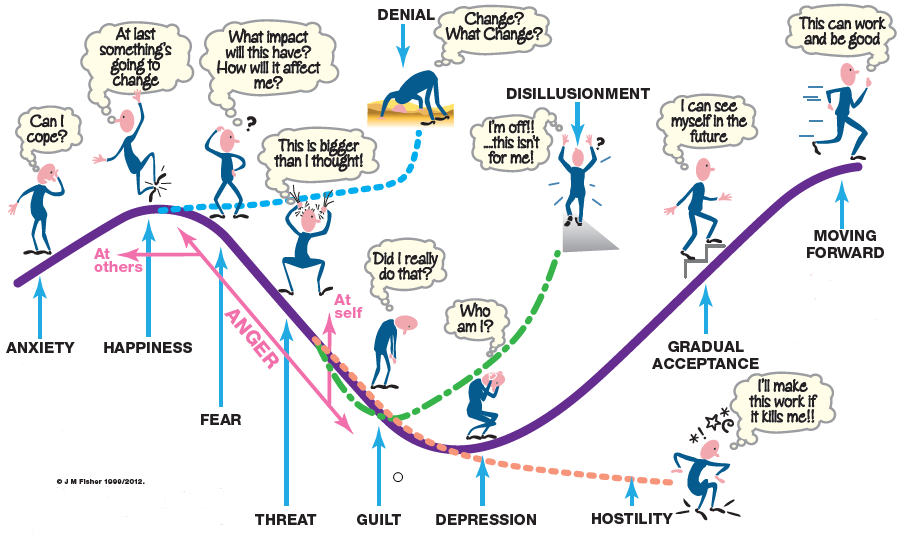

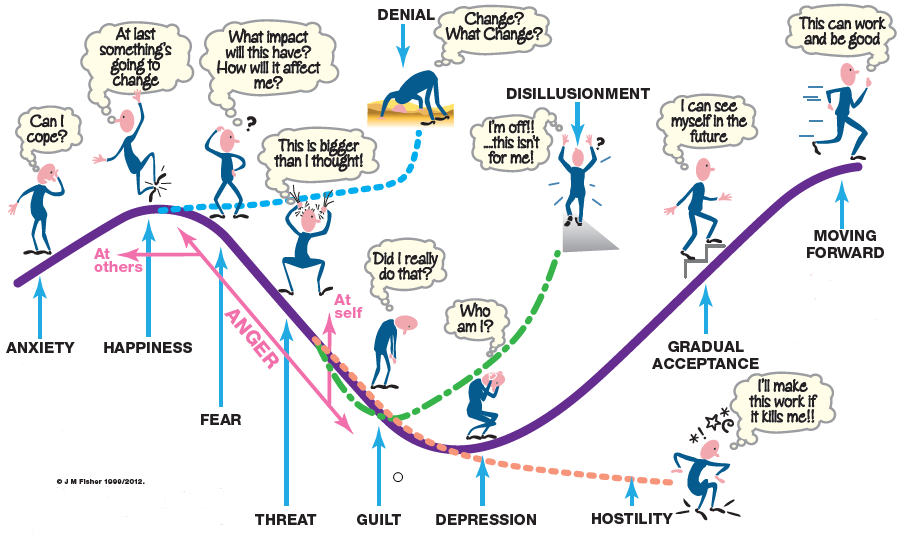

Some years later I was introduced to the Nerve Curve which is the emotional roller-coaster ride that accompanies change. Any form of change.

The multi-step model was described in the context of bereavement by psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross in her 1969 book “On Death & Dying: What the Dying Have to Teach Doctors, Nurses, Clergy and their Families.“

More recently this grief reaction has been extended and applied by authors such as William Bridges and John Fisher in the less emotionally traumatic contexts called transitions.

The characteristic sequence of emotions are triggered by external events are:

- shock

- denial

- frustration

- blame

- guilt

- depression

- acceptance

- engagement

- excitement.

The important messages in both of these models is that (a) this is a normal and expected process and (b) we can get stuck along the path of transition. We can disengage at several points, signalling to others that we have come off the track. When we do that we exhibit behaviours such as denial, disillusionment and hostility.

More recently I was introduced to the work of the late Chris Argyris and specifically the concept of “defensive reasoning“.

The essence of the concept: As we start to become aware of a gap between our intentions and our impact, then we feel threatened and our natural emotional reaction is defensive. This is the essence of the behaviour called “resistance to change”, and it is interesting to note that “smart” people are particularly adept at it.

These three concepts are clearly related in some way. But how?

As a systems engineer I am used to cyclical processes and the concepts of wavelength, amplitude, phase and offset, and I found myself looking at the Awareness-Ability cycle and asking:

“How could that cycle generate the characteristic shape of the transition curve?”

Then the Argyris idea of the gap between intent and impact popped up and triggered another question:

“What if we look at the gap between our ability and our awareness?”

So, I conducted a thought experiment and imagined myself going around the cycle – and charting my ability, awareness and emotional state along the way … and this sketch emerged. Ah ha!

When my awareness exceeded my ability I felt disheartened. That is the defensive reasoning that Chris Argyris talks about, the emotional barrier to self-improvement.

But that sense is, paradoxically, associated with the steepest part of the learning curve. It is almost as it there is a piece of emotional elastic linking the blue and green lines and how we feel is related to how much it is being stretched and in what direction.

This insight suggested to me that the process of building self-engagement requires opening the ability-versus-awareness gap a little-bit-at-a-time, then sensing the emotional discomfort, and then actively releasing the tension by learning a new concept, principle, technique or tool (and usually all four). That makes sense.