People who work in health care are risk averse. There is a good reason for this. Taking risks can lead to harmed and unhappy patients and that can lead to complaints and litigation.

This principle of “first do no harm” has a long history that dates back to the Greek Physician Hippocrates of Kos who was born about 2500 years ago. The Hippocratic school revolutionised medicine and established it a discipline and as a profession. And with the benefit of 2500 years of practice we now help, heal and do no harm.

Unintended harm is a form of failure and no one likes to feel that they have failed. We feel a sense of anxiety or even fear of failure that can become disabling to the point where we are not even prepared to try.

There are many words associated with failure and three that are commonly used are errors, mistakes and slips. These are often conflated but they are not quite the same thing.

It is important to be aware that failure is an output or outcome, while errors and mistakes are part of the process that lead to the outcome.

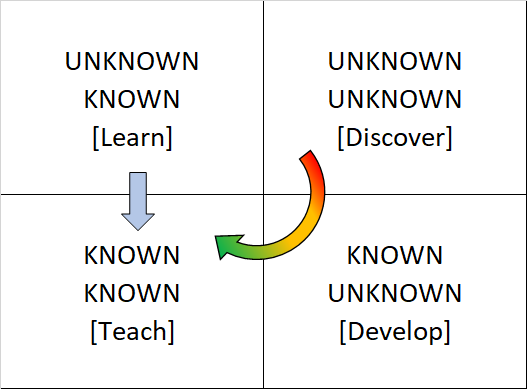

To help illustrate the difference between errors and mistakes it is useful to consider how knowledge is created.

At the start no one knows anything and do not even know what they need to know. This is the zone of Unknown Unknowns. At the end of the knowledge creating process everyone knows everything they need to know. This is the zone of Known Knowns.

Between these end points is a process of learning and development. First we become aware of what we need to know, and then we focus growing that know-how. Finally we focus in how to apply and teach these known knowns. It is not necessary for everyone to discover everything for themselves. We can learn from each other.

The term error is a generic overarching term that includes mistakes and slips, so it is is useful to tease out the nuances.

We make a error when we do not use what is already a known known.

For example, I know how to use a calculator to add up a set of numbers but if I accidentally press a wrong button then I will fail to get the correct result. That is an avoidable failure. I made an error. This type of error is also called a slip.

If I do not read the instructions of how to use the calculator, and I press the wrong buttons deliberately, in the erroneous belief that they are correct, then I will fail to get the correct result. I made an error.

There are two different types of error here. One is an error of commission which is when I do the wrong thing (i.e. I do press the wrong button). The other is an error of omission and is when I do not do the right thing (i.e. I do not read the instructions). Not learning and using what is already known has a name, it is called ineptitude. We could also call it the zone of Unknown Knowns. We escape it by learning what is known.

One observable consequence of a failure that results from a well-intended-but-inept action is surprise, shock and denial. And we often repeat the same action in the hope that the intended outcome happens next time. When it doesn’t we feel a sense of confusion and frustration. That frustration can bubble out as anger and manifest as a behaviour called blame. This phenomenon also has a name, it is called hubris.

Errors of omission often cause more problems because they are harder to see. We are quite literally blind to them. To spot an error of omission we need to know what to look for that is missing, which means we need to know what is known.

Mistakes are different.

We make mistakes when we are working at the edge of our knowledge and we do something that we believe will work but only partly achieves what we intend. We know we are on the right track and we know we do not yet have all the knowledge we need. This is the zone of Known Unknowns. It is the appropriate place for research, experimentation, development, learning and improvement. This is an iterative process of learning from both successes and failures causd by mistakes.

The term mistake implies a cognitive error.

Mistakes are expected in the learning zone and over time they become fewer and fewer as we learn from them and apply that learning. Eventually we know all that we need to achieve our intended outcome and we enter the zone of Known Knowns. This is how we all learned to walk and talk and to do most of the things that, with practice, become second nature.

In a safety-critical system like health care we cannot afford to make errors and mistakes and we need to know which knowledge zone we are in. If we experience a failure we must be able to differentiate an error from a mistake, and an error from a slip. This is because what happens next will be different – especially if the outcome is a harmed, unhappy patient.

An error or slip implies that the harm was avoidable because the know-how was available. In an error situation it becomes a question of ineptitude or negligence or inattention. If appropriate training is available and is not taken up, or taken up and not applied, then that is negligence. This is easily confused with ineptitude that results when appropriate training is not available or not effective. Slips happen when we are not paying attention.

One example of this is where new medical information systems are implemented and the users are not given sufficient time and offered effective training to use them correctly. Errors will inevitably result and patients may be harmed as a consequence. The error here is one of omission – i.e. omitting to ensure users are trained and competent to use the new system correctly. At best it is an example of management ineptitude, at worst it is management negligence. It is a management system failure and is avoidable.

Slips often happen when were are busy, rushing or are interrupted and we are not paying enough attention to what we are doing.

Thus far we have been making a tacit assumption that we have not stated – that all failures are bad and should be avoided. This is certainly true in the zone of Known Knowns, but what about in the zone of Unknown Unknowns? The zone of Discovery and Innovation.

Paradoxically, failures here are expected and welcomed because everything new that we try-and-fail is a piece of useful knowledge. The goal here is to fail fast so that we can try as many times as possible and learn what does-not-work as fast as possible . The Laws of Chance say that the more different attempts we make, the more likely one of them will succeed. Louis Pasteur said “Chance favours the prepared mind” and even random attempts are better than none. Rational attempts are even better. Thomas Edison, the famous inventor and developer of a practical incandescent lamp, failed many times before finding a design that worked.

So, when something does not turn out as intended or expected pause to ponder whether it was an avoidable error, a slip, a well-intended mistake, or just another stab at making a hole the dark cloak of ignorance and letting in some enlightenment.

And just as importantly when something does turn out as expected then pause to ponder whether it was expected, desired or unexpected. Positive surprises happen all the time.

So, it is dangerous to believe that we can only learn by making errors and mistakes. Whatever outcome we get, success or failure, is an opportunity to learn.

And, when we are not sure we can always ask because it is quite likely that our Unknown is someone else’s Known. Humilty and curiosity go together.