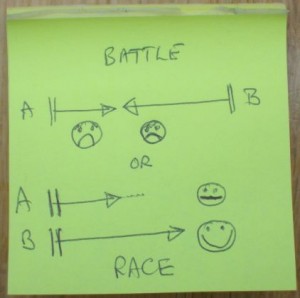

Do you see the challenges that Life presents to you as a series of fight-to-the-death battles or a series of stretch-for-the-finish races? Why does it matter which approach you choose? After all, each has a winner and a loser. Yes, one wins relative to other – but what is the absolute cost for both? The doodle illustrates the point visually. In a Battle you are in opposition and your effort, time and money are spent and dissipated against each other. The strong/angry/big will prevail over the weak/timid/small though when the protagnoists are closely matched the outcome takes longer to decide and costs more in absolute terms for both. One will eventually win while both are weakened from the effort, time and money that is spent. Contrast this with the race; the investment on both sides is in preparing for the race; in learning, training, and improving. On the day of the race the more fit/focussed/skilled competitor will win yet both are strengthened from the invested effort, time and money. In a race the more closely you are matched the more you both improve and get stronger and the quicker the outcome is decided. Exactly the opposite of the battle. It appears that Life will present us with enough new challenges to keep us occupied for the forseeable future; and to rise to those challenges will require that we all learn, train, and practice so that we have the strength, skills and stamina for the challenges we will encounter and cannot yet see. So, it seems to me to be suicidal to choose to battle with each other and to waste our limited resources of effort, time and money to the point where we are all too weak to survive the inevitable challenges that are over the horizon. So how would you know which approach you are using? Well, your feelings are more often sadness, anger or fear then you are probably using the battle metaphor; if in contrast they are feelings of confidence, determination and excitement then you probably see yourself in a race. The choice is yours.

Do you see the challenges that Life presents to you as a series of fight-to-the-death battles or a series of stretch-for-the-finish races? Why does it matter which approach you choose? After all, each has a winner and a loser. Yes, one wins relative to other – but what is the absolute cost for both? The doodle illustrates the point visually. In a Battle you are in opposition and your effort, time and money are spent and dissipated against each other. The strong/angry/big will prevail over the weak/timid/small though when the protagnoists are closely matched the outcome takes longer to decide and costs more in absolute terms for both. One will eventually win while both are weakened from the effort, time and money that is spent. Contrast this with the race; the investment on both sides is in preparing for the race; in learning, training, and improving. On the day of the race the more fit/focussed/skilled competitor will win yet both are strengthened from the invested effort, time and money. In a race the more closely you are matched the more you both improve and get stronger and the quicker the outcome is decided. Exactly the opposite of the battle. It appears that Life will present us with enough new challenges to keep us occupied for the forseeable future; and to rise to those challenges will require that we all learn, train, and practice so that we have the strength, skills and stamina for the challenges we will encounter and cannot yet see. So, it seems to me to be suicidal to choose to battle with each other and to waste our limited resources of effort, time and money to the point where we are all too weak to survive the inevitable challenges that are over the horizon. So how would you know which approach you are using? Well, your feelings are more often sadness, anger or fear then you are probably using the battle metaphor; if in contrast they are feelings of confidence, determination and excitement then you probably see yourself in a race. The choice is yours.

Anyone Heard of Henry Gantt?

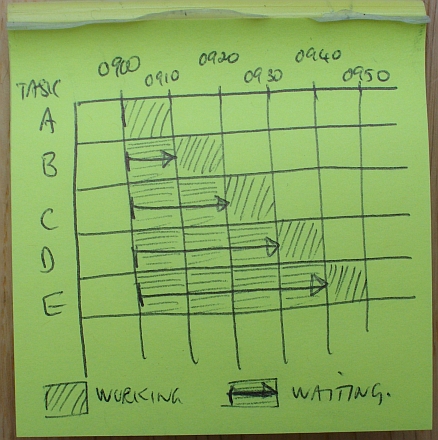

Most managers have heard of Gantt charts and associate them with project management where they are widely used to help coordinate the separate threads of work so that the project finishes on time.

Most managers have heard of Gantt charts and associate them with project management where they are widely used to help coordinate the separate threads of work so that the project finishes on time.

How many know about the man who invented them and why?

Henry Laurence Gantt (1861-1919) was an engineer and he invented the chart for a very different purpose – so that the workers and the managers could see at a glance the progress of the work and to see what was impairing the flow. Decades before the invention of the computer, Henry Gantt created a simple and incredibly powerful visual tool for enabling workers and managers to improve processes together.

I know how simple and powerful the original Gantt chart is because I use it all the time for capturing the behaviour of a process in a visual form that stimulates constructive conversations which result in win-win-win improvements. All you need is some squared paper, a pencil, a clock, a Mark I Eyeball or two, and a bit of practice.

Delusional Ratios and Arbitrary Targets

This week a friend of mine shared an interesting story.

They were told that their recent performance data showed that performance was improving. “That sounds good” they thought as they started to look at the data which was presented as a table of numbers, one number per time period, as a percentage ratio, and colour coded red, amber or green. The last number in the sequence was green; the previous ones were either red or amber. “See! Our performance has improved and is now acceptable“.

But it did not feel quite right to my friend who did not want to dampen the celebration without good reason, so enquired further “What is the ratio measuring exactly?” “H’mm, let me check, the number of failures divided by the number of customer requests.” “And what does the red, amber and green signify?” “Oh that’s easy, whether we are above, near or below our target.” “And how was the target set and by whom?” “Um, I don’t know how it was set, we were just told what the target is and the consequences if we don’t meet it.” “And what are the consequences?” No answer – just a finger-across-the-throat gesture. “Can I see the raw data used to calculate this ratio?” “Eh? I think so, but no one has ever asked us for that before.”

My friend could now see the origin of his niggle of doubt. The raw data showed that the number of customer requests was falling progressively over time while the number of successful requests was not changing. They were calculating failures from the difference between demand and activity and then dividing the result by the demand to give a percentage that was intended to show their performance. And then setting an arbitrary target for acceptability.

The raw data told a very different story – their customers were going elsewhere – which meant their future income was progressively walking away. They were blind to it; their ratio was deluding them.

And by setting an arbitrary target for this “delusional ratio” implied that so long as they were “in the green” they didn’t need to do anything, they could sit back and relax. They could not see the nasty surprise coming.

This story led me to wonder how many organsiations get into trouble by following delusional ratios linked to arbitrary targets? How many never see the storm coming until it is too late to avoid it? Where do these delusional ratios and arbitrary targets come from? Do they have a valid and useful purpose? And if so, how do we know when to use a ratio or a target and when not to?

It also gave me a new acronym – D.R.A.T. – which seems rather appropriate.

Inspired by actual events

This Sunday I was listening the Aled Jones on Radio 2 – as he was interviewing Mark Kermode of BBC.TV’s Culture Show. Mark posed a profound question:

When you visit the cinema, do you like to watch the kind of film that starts with a caption saying “This is a True Story” or maybe you prefer the kind with a caption saying “This is a story inspired by Actual Events”?

He suggested that it’s best to assume that the first kind is largely a fiction, whereas the latter is almost completely so. Personally, I don’t mind which ever kind it is, for sometimes I actually enjoy being fooled as long as it’s good harmless fun and it’s entertaining – AND as long as I don’t think someone is deliberately fooling me. But then I started wondering: How would I know if they were trying to fool me? Or more worryingly, whether I was fooling myself?

Since the 1850s there have been various “Realism” movements in the fields of cinema, art and literature – featuring the search for literal truth and pragmatism – a representation of objects, actions, or social conditions as they actually are without idealisation or presentation in abstract form – each of these movements was based upon a philosophy that universals exist independently of their having been thought up, and that physical objects exist independently of their being perceived. In this age of political and media “spin” maybe there’ll come a return to such a philosophy? In the mean time, as long as we are aware that the film we’ve chosen to watch is intended as fiction, and is billed as such, most of us won’t mind – indeed we might even view it as escapism – yet in many situations wouldn’t it be nice to feel that we are connected to a representation of events that’s more real, rather than just some one else’s imagined story?

When a patient in the healthcare system, I think I’d rather be treated by professionals who check and double check what they’re doing, and are working within a system that someone has designed to be fail safe – and is measured to be so. I’m hoping that the medics, nurses and administrators know the difference between what’s real and what is imagined. On this week’s Panorama (BBC March 8th 2010) it was suggested that some hospitals have much higher mortality than others, so this isn’t an insignificant hope. The three hospitals featured had all been flagged as having high mortality rates, yet had all been rated “Fair” or “Good” by the Care Quality Commission. This left me thinking that their may be more imagination around in the NHS than hard data.

The thing is, most everyone relies on data (via their 5 senses or their intuition) as if pure and unfiltered – under the assumption that this is all there is. But there’s always more to be known, and some of that missing knowledge may literally be the difference between life and death.

Numerical data in particular is actively avoided by many – even by professionals, be they the designers of the system or an individual who works within it. Many people left school determined to avoid numbers for the rest of their lives – when confronted by even the simplest statistic or numerical puzzle they will happily tell you “I don’t do numbers.” Since seeing the Panorama programme I’m now wondering how many people (clinicians, managers, inspectors) working within the health sector take such a view. Or maybe there’s a full-proof test that every prospective healthcare worker must pass before they’re allowed to practice? Can anyone reasure me about this?

A few weeks ago some very powerful yet delightfully accessible software was launched – called BaseLine©. It has been created so that people can have a kind of 3rd eye perception that mitigates the tendency to fictionalise – so that people can together assess what’s really happening. It’s designed to be a kind of dispassionate “fly on the wall” or a well-positioned “security camera” – and has been designed to be so easy to use that even the numerophobic will want to use it.

It’s actually free software, and even the full version costs under £50 – this is deliberate in order to maximize the possibility of it becoming a health sector standard. Having a standard tool will mean that people won’t have to debate the validity of the statistics, and can move directly to discussing the reality of what’s been happening, what’s happening now, and more importantly what’s likely to happen if nothing changes. Let’s see how long it takes clinicians and managers to discover its power?

www.saasoft.co.uk

What is the Dis-Ease?

Do you ever go into places where there is a feeling of uneasiness?

Do you ever go into places where there is a feeling of uneasiness?

You can feel it almost immediately – there is something in the room that no one is talking about.

An invisible elephant in the room, a rotting something under the table.

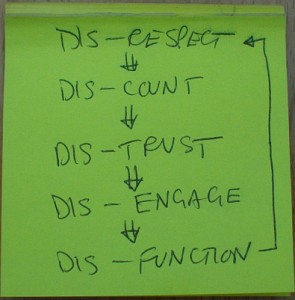

This week I have been pondering the cause of this dis-ease and my eureka moment happened while re-reading a book called “The Speed of Trust” by Stephen R. Covey.

A common elephant-in-the-room appears to be distrust and this got me thinking about both the causes of distrust and the effects of distrust. My doodle captures the output of my musing. For me, a potent cause of distrust is to be discounted; and discounting comes from disrespect. This can happen both within yourself and between yourself and others. If you feel un-trust-worthy then you tend to disengage; and by disengaging the system functions less well – it becomes dysfunctional. Dysfunction erodes respect and so on around the vicious circle.

This then led me to the question: Why haven’t we all drowned in our own distrust by now? I believe what happens is that we reach an equilibrium where our level of trust is stable; so there must be a counteracting trust-building force that balances the trust-eroding force. That trust-building force seem to comes from our day-to-day social interactions with others.

The Achilles Heel of negative-cause-effect circles is that you can break into them at many points to sap their power and reduce their influence. So, one strategy might be to identify the Errors of Commission that create the Disease of Distrust.

Consider the question: “If I have developed a high level of trust then what could I do to erode it as quickly as possible?”.

Disrespectful attitude and discounting behaviour would be all that is needed to start the vicious downward spiral of distrust disease.

Who of us never disrespects or discounts others?

Are we all infected with the same disease?

Is there a cure or can we only expect to hold it in remission?

How can we strengthen our emotional immune systems and neutralise the infective agents of the Disease of Distrust?

Do we just need to identify and stop our trust eroding behaviour?

That would be a start.