There is a Catch-22 in health care improvement and it goes a bit like this:

Most people are too busy fire-fighting the chronic chaos to have time to learn how to prevent the chaos, so they are stuck.

There is a deeper Catch-22 as well though:

The first step in preventing chaos is to diagnose the root cause and doing that requires experience, and we don’t have that experience available, and we are too busy fire-fighting to develop it.

Health care is improvement science in action – improving the physical and psychological health of those who seek our help. Patients.

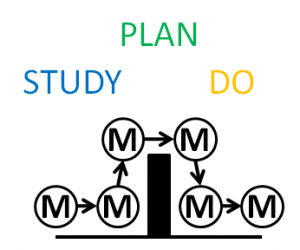

And we have a tried-and-tested process for doing it.

First we study the problem to arrive at a diagnosis; then we design alternative plans to achieve our intended outcome and we decide which plan to go with; and then we deliver the plan.

Study ==> Plan ==> Do.

Diagnose ==> Design & Decide ==> Deliver.

But here is the catch. The most difficult step is the first one, diagnosis, because there are many different illnesses and they often present with very similar patterns of symptoms and signs. It is not easy.

And if we make a poor diagnosis then all the action plans that follow will be flawed and may lead to disappointment and even harm.

Complaints and litigation follow in the wake of poor diagnostic ability.

So what do we do?

We defer reassuring our patients, we play safe, we request more tests and we refer for second opinions from specialists. Just to be on the safe side.

These understandable tactics take time, cost money and are not 100% reliable. Diagnostic tests are usually precisely focused to answer specific questions but can have false positive and false negative results.

To request a broad batch of tests in the hope that the answer will appear like a rabbit out of a magician’s hat is … mediocre medicine.

This diagnostic dilemma arises everywhere: in primary care and in secondary care, and in non-urgent and urgent pathways.

And it generates extra demand, more work, bigger queues, longer delays, growing chaos, and mounting frustration, disappointment, anxiety and cost.

The solution is obvious but seemingly impossible: to ensure the most experienced diagnostician is available to be consulted at the start of the process.

But that must be impossible because if the consultants were seeing the patients first, what would everyone else do? How would they learn to become more expert diagnosticians? And would we have enough consultants?

When I was a junior surgeon I had the great privilege to have the opportunity to learn from wise and experienced senior surgeons, who had seen it, and done it and could teach it.

Mike Thompson is one of these. He is a general surgeon with a special interest in the diagnosis and treatment of bowel cancer. And he has a particular passion for improving the speed and accuracy of the diagnosis step; because it can be a life-saver.

Mike Thompson is one of these. He is a general surgeon with a special interest in the diagnosis and treatment of bowel cancer. And he has a particular passion for improving the speed and accuracy of the diagnosis step; because it can be a life-saver.

Mike is also a disruptive innovator and an early pioneer of the use of endoscopy in the outpatient clinic. It is called point-of-care testing nowadays, but in the 1980’s it was a radically innovative thing to do.

He also pioneered collecting the symptoms and signs from every patient he saw, in a standard way using a multi-part printed proforma. And he invested many hours entering the raw data into a computer database.

He also did something that even now most clinicians do not do; when he knew the outcome for each patient he entered that into his database too – so that he could link first presentation with final diagnosis.

Mike knew that I had an interest in computer-aided diagnosis, which was a hot topic in the early 1980’s, and also that I did not warm to the Bayesian statistical models that underpinned it. To me they made too many simplifying assumptions.

The human body is a complex adaptive system. It defies simplification.

Mike and I took a different approach. We just counted how many of each diagnostic group were associated with each pattern of presenting symptoms and signs.

The problem was that even his database of 8000+ patients was not big enough! This is why others had resorted to using statistical simplifications.

So we used the approach that an experienced diagnostician uses. We used the information we had already gleaned from a patient to decide which question to ask next, and then the next one and so on.

And we always have three pieces of information at the start – the patient’s age, gender and presenting symptom.

What surprised and delighted us was how easy it was to use the database to help us do this for the new patients presenting to his clinic; the ones who were worried that they might have bowel cancer.

And what surprised us even more was how few questions we needed to ask arrive at a statistically robust decision to reassure-or-refer for further tests.

So one weekend, I wrote a little computer program that used the data from Mike’s database and our simple bean-counting algorithm to automate this process. And the results were amazing. Suddenly we had a simple and reliable way of using past experience to support our present decisions – without any statistical smoke-and-mirror simplifications getting in the way.

The computer program did not make the diagnosis, we were still responsible for that; all it did was provide us with reliable access to a clear and comprehensive digital memory of past experience.

What it then enabled us to do was to learn more quickly by exploring the complex patterns of symptoms, signs and outcomes and to develop our own diagnostic “rules of thumb”.

We learned in hours what it would take decades of experience to uncover. This was hot stuff, and when I presented our findings at the Royal Society of Medicine the audience was also surprised and delighted (and it was awarded the John of Arderne Medal).

So, we called it the Hot Learning System, and years later I updated it with Mike’s much bigger database (29,000+ records) and created a basic web-based version of the first step – age, gender and presenting symptom. You can have a play if you like … just click HERE.

So what are the lessons here?

- We need to have the most experienced diagnosticians at the start of the improvement process.

- The first diagnostic assessment can be very quick so long as we have developed evidence-based heuristics.

- We can accelerate the training in diagnostic skills using simple information technology and basic analysis techniques.

And exactly the same is true in the health care system improvement.

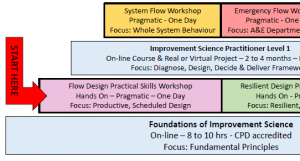

We need to have an experienced health care improvement practitioner involved at the start, because if we skip this critical study step and move to plan without a correct diagnosis, then we will make errors, poor decisions, and counter-productive actions. And then generate more work, more queues, more delays, more chaos, more distress and increased costs.

Exactly the opposite of what we want.

Q1: So, how do we develop experienced improvement practitioners more quickly?

Q2: Is there a hot learning system for improvement science?

A: Yes, there is. It can be found here.