This week I had the great pleasure of watching Dr Don Berwick sharing the story of his own ‘near religious experience‘ and his conversion to a belief that a Science of Improvement exists. In 1986, Don attended one of W.Edwards Deming’s famous 4-day workshops. It was an emotional roller coaster ride for Don! See here for a link to the whole video … it is worth watching all of it … the best bit is at the end.

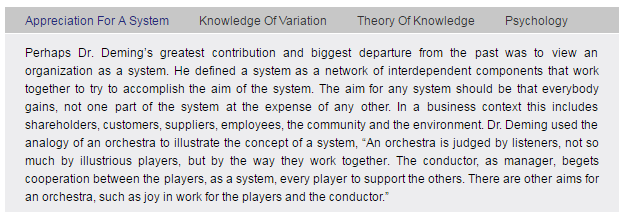

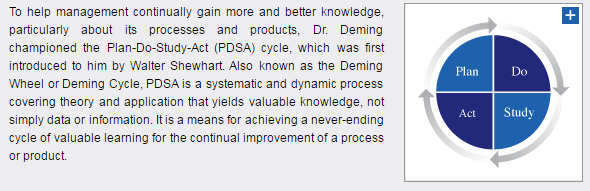

Don outlines Deming’s System of Profound Knowledge (SoPK) and explores each part in turn. Here is a summary of SoPK from the Deming website.

W.Edwards Deming was a physicist and statistician by training and his deep understanding of variation and appreciation for a system flows from that. He was not trained as a biologist, psychologist or educationalist and those parts of the SoPK appear to have emerged later.

Here are the summaries of these parts – psychology first …

Neurobiologists and psychologists now know that we are the product of our experiences and our learning. What we think consciously is just the emergent tip of a much bigger cognitive iceberg. Most of what is happening is operating out of awareness. It is unconscious. Our outward behaviour is just a visible manifestation of deeply ingrained values and beliefs that we have learned – and reinforced over and over again. Our conscious thoughts are emergent effects.

So how do we learn? How do we accumulate these values and beliefs?

This is the summary of Deming’s Theory of Knowledge …

But to a biologist, neuroanatomist, neurophysiologist, doctor, system designer and improvement coach … this does not feel correct.

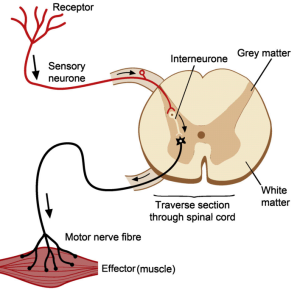

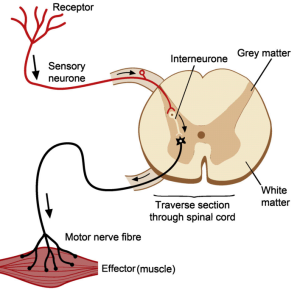

At the most fundamental biological level we do not learn by starting with a theory; we start with a sensory. The simplest element of the animal learning system – the nervous system – is called a reflex arc.

First, we have some form of sensor to gather data from the outside world. Eyes, ears, smell, taste, touch, temperature, pain and so on. Let us consider pain.

First, we have some form of sensor to gather data from the outside world. Eyes, ears, smell, taste, touch, temperature, pain and so on. Let us consider pain.

That signal is transmitted via a sensory nerve to the processor, the grey matter in this diagram, where it is filtered, modified, combined with other data, filtered again and a binary output generated. Act or Not.

If the decision is ‘Act’ then this signal is transmitted by a motor nerve to an effector, in this case a muscle, which results in an action. The muscle twitches or contracts and that modifies the outside world – we pull away from the source of pain. It is a harm avoidance design. Damage-limitation. Self-preservation.

Another example of this sensor-processor-effector design template is a knee-jerk reflex, so-named because if we tap the tendon just below the knee we can elicit a reflex contraction of the thigh muscle. It is actually part of a very complicated, dynamic, musculoskeletal stability cybernetic control system that allows us to stand, walk and run … with almost no conscious effort … and no conscious awareness of how we are doing it.

But we are not born able to walk. As youngsters we do not start with a theory of how to walk from which we formulate a plan. We see others do it and we attempt to emulate them. And we fail repeatedly. Waaaaaaah! But we learn.

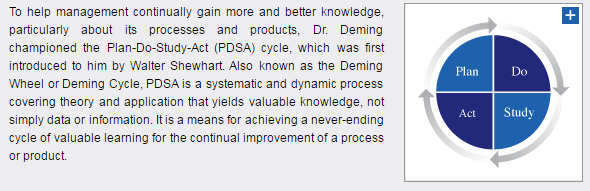

Human learning starts with study. We then process the sensory data using our internal mental model – our rhetoric; we then decide on an action based on our ‘current theory’; and then we act – on the external world; and then we observe the effect. And if we sense a difference between our expectation and our experience then that triggers an ‘adjustment’ of our internal model – so next time we may do better because our rhetoric and the reality are more in sync.

The biological sequence is Study-Adjust-Plan-Do-Study-Adjust-Plan-Do and so on, until we have achieved our goal; or until we give up trying to learn.

So where does psychology come in?

Well, sometimes there is a bigger mismatch between our rhetoric and our reality. The world does not behave as we expect and predict. And if the mismatch is too great then we are left with feelings of confusion, disappointment, frustration and fear. (PS. That is our unconscious mind telling us that there is a big rhetoric-reality mismatch).

We can see the projection of this inner conflict on the face of a child trying to learn to walk. They screw up their faces in conscious effort, and they fall over, and they hurt themselves and they cry. But they do not want us to do it for them … they want to learn to do it for themselves. Clumsily at first but better with practice. They get up and try again … and again … learning on each iteration.

Study-Adjust-Plan-Do over and over again.

There is another way to avoid the continual disappointment, frustration and anxiety of learning. We can distort our sensation of external reality to better fit with our internal rhetoric. When we do that the inner conflict goes away.

We learn how to tamper with our sensory filters until what we perceive is what we believe. Inner calm is restored (while outer chaos remains or increases). We learn the psychological defense tactics of denial and blame. And we practice them until they are second-nature. Unconscious habitual reflexes. We build a reality-distortion-system (RDS) and it has a name – the Ladder of Inference.

And then one day, just by chance, somebody or something bypasses our RDS … and that is the experience that Don Berwick describes.

Don went to a 4-day workshop to hear the wisdom of W.Edwards Deming first hand … and he was forced by the reality he saw to adjust his inner model of the how the world works. His rhetoric. It was a stormy transition!

The last part of his story is the most revealing. It exposes that his unconscious mind got there first … and it was his conscious mind that needed to catch up.

Study-(Adjust)-Plan-Do … over-and-over again.

In Don’s presentation he suggests that Frederick W. Taylor is the architect of the failure of modern management. This is a commonly held belief, and everyone is equally entitled to an opinion, that is a definition of mutual respect.

But before forming an individual opinion on such a fundamental belief we should study the raw evidence. The words written by the person who wrote them not just the words written by those who filtered the reality through their own perceptual lenses. Which we all do.