There is no doubt about it: Change is Difficult. None of us like it. We all prefer the comfort and security of sameness. We are wired that way. Yet, change is inevitable. So, what can we do?

One option is to ignore it. Another is to resist it. And another is to make the best of it. It is even possible to embrace and celebrate it!

And what if we are responsible for managing change that will have an effect on others? That is a whole order of magnitude more difficult. There is an oft quoted statistic that 70% of change initiatives fail – which proves that it must be more difficult than the originators anticipated. Yet, if we look around we can see examples of successful change everywhere – so it must be possible to manage it. How is it done? What are the traps to avoid? What do we need? What don’t we need? Where do we start? Who can we ask for guidance?

If we search the Web or use an AI assistant like ChatGPT, we will discover a multitude of change models such as Kurt Lewin’s Unfreeze-Change-Refreeze model or John Kotter’s Eight Steps. And if we compare and contrast these recipes we will find common themes such as the importance of leadership, and vision and a clear plan. That all makes sense.

What is more difficult to find are root cause analyses of failed changes that we can learn from. No one likes to talk about their failures but we need to compare the successes and failures to find the nuggets of wisdom that we can learn from and use to reduce the risk of failure for our own change initiatives. “Learn to fail or fail to learn” as they say.

And how do we know if we are on track? What are the early warning signs of an impending failure that we could use to get us back on track or give us the confidence to abandon the attempt before too much time, money, blood, sweat and tears are wasted?

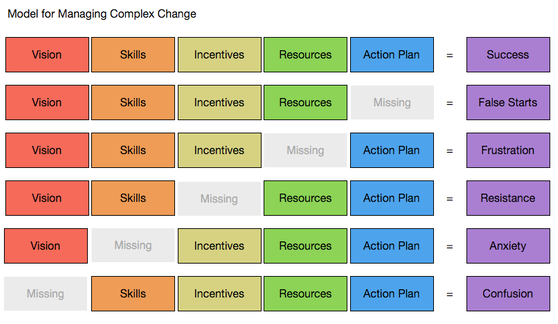

These are questions that have been buzzing around for years and recently I chanced across something that caught my eye. It was diagram that I had not come across before.

Two things immediately struck me. The first was the explicit inclusion of “Skills’ in the recipe for success. That made sense to me. The second was the symptoms of what happens if an ingredient of the complex change recipe is missing. Those made sense to me too because I have experienced them all.

The diagram I found was not attributed so I did a bit of searching – using the five ingredients as a starter. What I discovered was fascinating – a sort of Chinese Whispers story with different names attached to emergent variants of the diagram. I persevered and eventually found the original source – Dr Mary Lippitt who created and copyrighted the diagram in 1987.

The next thing I did was float the Lippitt diagram with other people who are actively working in applying the science of improvement in the health care sector – and who are faced with the challenge of having to manage complex change. The Lippitt diagram resonated strongly with them too – which I saw as a good sign.

I then found Dr Mary Lippitt’s email address and emailed her, out of the blue. And she replied almost immediately, thanked me, and we arranged to have a Zoom chat. It was fascinating. What I learned was that her passion for complex change blossomed when she inherited her father Gordon’s consulting business. He, like his older brother Ronald, worked in the organisational change domain and Gordon wrote a book entitled “Organization Renewal” whose second edition was published in 1982. And I discovered that Ronald Lippitt was a colleague of Kurt Lewin – the Father of Social Psychology. So, the pedigree of the diagram I came across by chance is impeccable!

Changing even a small part of a health care system is a tough sociotechnical challenge and I have learned the hard way that a combination of social and technical skills are required. Many of these skills appear to be missing in health care organisations and that skills gap leads to the most common source of resistance to change that I see: Anxiety.

It also goes some way to explain why we made significant progress in delivering health care service improvements when we focussed on giving the front line staff:

a) the required skills to diagnose the causes of their service issues, and

b) the required skills to redesign their processes to release the improvements they wanted to see.

We now have good evidence that, unwittingly, we also developed the complementary social skills to help spread the word of what is possible and how to achieve it organically across teams, departments and organisations.

So, with her generous permission, we will be using Dr Mary Lippitt’s diagram to tell the story of how to manage complex change. And we will share what we learn as we go.