Previously we have explored “costs” associated with processes and systems – costs that could be avoided through the effective application of Improvement Science. The Cost of Errors. The Cost of Queues. The Cost of Variation.

These costs are large, additive and cumulative and yet they pale into insignificance when compared with the most potent source of cost. The Cost of Distrust.

The picture is of Sue Sheridan and the link below is to a video of Sue telling her story of betrayed trust: in a health care system. She describes the tragic consequences of trust-eroding health care system behaviour. Sue is not bitter though – she remains hopeful that her story will bring everyone to the table of Safety Improvement

View the Video

The symptoms of distrust are easy to find. They are written on the faces of the people; broadcast in the way they behave with each other; heard in what they say; and felt in how they say it. The clues are also in what they do not do and what they do not say. What is missing is as important as what is present.

There are also tangible signs of distrust too – checklists, application-for-permission forms, authorisation protocols, exception logs, risk registers, investigation reports, guidelines, policies, directives, contracts and all the other machinery of the Bureaucracy of Distrust.

The intangible symptoms of distrust and the tangible signs of distrust both have an impact on the flow of work. The untrustworthy behaviour creates dissatisfaction, demotivation and conflict; the bureaucracy creates handoffs, delays and queues. All are potent sources of more errors, delays and waste.

The Cost of Distrust is is counted on all three dimensions – emotional, temporal and financial.

It may appear impossible to assign a finanical cost of distrust because of the complex interactions between the three dimensions in a real system; so one way to approach it is to estimate the cost of a high-trust system. A system in which the trustworthy behaviour is explicit and trust eroding behaviour is promptly and respectfully challenged.

Picture such a system and consider these questions:

- How would it feel to work in a high-trust system where you know that trust-eroding-behaviour will be challenged with respect?

- How would it feel to be the customer of a high-trust system?

- What would be the cost of a system that did not need the Bureaucracy of Distrust to deliver safety and quality?

Trust eroding behaviours are not reduced by decree, threat, exhortation, name-shame-blame, or pleading because all these behaviours are based on the assumption of distrust and say “I do not trust you to do this without my external motivation”. These attitudes behaviours give away the “I am OK but You are Not OK” belief.

Trust eroding behaviours are most effectively reduced by a collective charter which is when a group of people state what behaviours they do not expect and individually commit to avoiding and challenging. The charter is the tangible sign of the peer support that empowers everyone to challenge with respect because they have collective authority to do so. Authority that is made explicit through the collective charter: “We the undersigned commit to respectfully challenge the following trust eroding behaviours …”.

It requires confidence and competence to open a conversation about distrust with someone else and that confidence comes from insight, instruction and practice. The easiest person to practice with is ourselves – it takes courage to do and it is worth the investment – which is asking and answering two questions:

Q1: What behaviours would erode my trust in someone else?

Make a list and rank on order with the most trust-eroding at the top.

Q2: Do I ever exhibit any of the behaviours I have just listed?

Choose just one from your list that you feel you can commit to – and make a promose to yourself – every time you demonstrate the behaviour make a mental note of:

- When it happened?

- Where it happened?

- Who was present?

- What just happened?

- How did you feel?

You do not need to actively challange your motives, or to actively change your behaviour – you just need to connect up your own emotional feedback loop. The change will happen as if by magic!

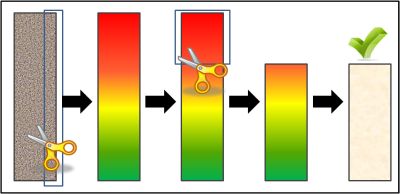

We are in now in cost cake cutting times! We are being forced by financial reality to tighten the fiscal belt until our eyeballs water – and then more so.

We are in now in cost cake cutting times! We are being forced by financial reality to tighten the fiscal belt until our eyeballs water – and then more so.