This week I conducted an experiment – on myself.

This week I conducted an experiment – on myself.

I set myself the challenge of measuring the cost of chaos, and it was tougher than I anticipated it would be.

It is easy enough to grasp the concept that fire-fighting to maintain patient safety amidst the chaos of healthcare would cost more in terms of tears and time …

… but it is tricky to translate that concept into hard numbers; i.e. cash.

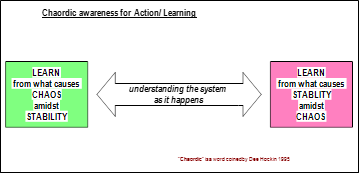

Chaos is an emergent property of a system. Safety, delivery, quality and cost are also emergent properties of a system. We can measure cost, our finance departments are very good at that. We can measure quality – we just ask “How did your experience match your expectation”. We can measure delivery – we have created a whole industry of access target monitoring. And we can measure safety by checking for things we do not want – near misses and never events.

But while we can feel the chaos we do not have an easy way to measure it. And it is hard to improve something that we cannot measure.

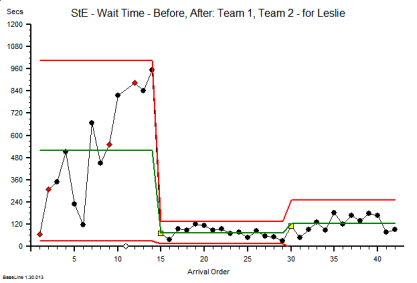

So the experiment was to see if I could create some chaos, then if I could calm it, and then if I could measure the cost of the two designs – the chaotic one and the calm one. The difference, I reasoned, would be the cost of the chaos.

And to do that I needed a typical chunk of a healthcare system: like an A&E department where the relationship between safety, flow, quality and productivity is rather important (and has been a hot topic for a long time).

But I could not experiment on a real A&E department … so I experimented on a simplified but realistic model of one. A simulation.

What I discovered came as a BIG surprise, or more accurately a sequence of big surprises!

- First I discovered that it is rather easy to create a design that generates chaos and danger. All I needed to do was to assume I understood how the system worked and then use some averaged historical data to configure my model. I could do this on paper or I could use a spreadsheet to do the sums for me.

- Then I discovered that I could calm the chaos by reactively adding lots of extra capacity in terms of time (i.e. more staff) and space (i.e. more cubicles). The downside of this approach was that my costs sky-rocketed; but at least I had restored safety and calm and I had eliminated the fire-fighting. Everyone was happy … except the people expected to foot the bill. The finance director, the commissioners, the government and the tax-payer.

- Then I got a really big surprise! My safe-but-expensive design was horribly inefficient. All my expensive resources were now running at rather low utilisation. Was that the cost of the chaos I was seeing? But when I trimmed the capacity and costs the chaos and danger reappeared. So was I stuck between a rock and a hard place?

- Then I got a really, really big surprise!! I hypothesised that the root cause might be the fact that the parts of my system were designed to work independently, and I was curious to see what happened when they worked interdependently. In synergy. And when I changed my design to work that way the chaos and danger did not reappear and the efficiency improved. A lot.

- And the biggest surprise of all was how difficult this was to do in my head; and how easy it was to do when I used the theory, techniques and tools of Improvement-by-Design.

So if you are curious to learn more … I have written up the full account of the experiment with rationale, methods, results, conclusions and references and I have published it here.