You develop some non-specific symptoms.

You see your GP who refers you urgently to a 2 week clinic.

You are seen, assessed, investigated and informed that … you have cancer!

The shock, denial, anger, blame, bargaining, depression, acceptance sequence kicks off … it is sometimes called the Kübler-Ross grief reaction … and it is a normal part of the human psyche.

But there is better news. You also learn that your condition is probably treatable, but that it will require chemotherapy, and that there are no guarantees of success.

You know that time is of the essence … the cancer is growing.

And time has a new relevance for you … it is called life time … and you know that you may not have as much left as you had hoped. Every hour is precious.

So now imagine your reaction when you attend your local chemotherapy day unit (CDU) for your first dose of chemotherapy and have to wait four hours for the toxic but potentially life-saving drugs.

They are very expensive and they have a short shelf-life so the NHS cannot afford to waste any. The Aseptic Unit team wait until all the safety checks are OK before they proceed to prepare your chemotherapy. That all takes time, about four hours.

Once the team get to know you it will go quicker. Hopefully.

It doesn’t.

The delays are not the result of unfamiliarity … they are the result of the design of the process.

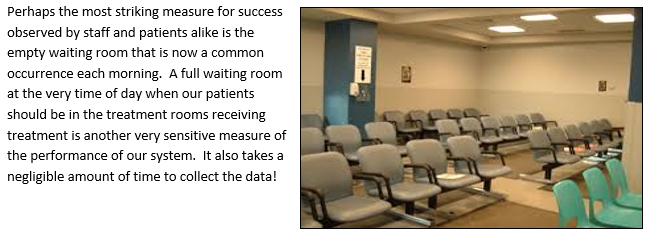

All your fellow patients seem to suffer repeated waiting too, and you learn that they have been doing so for a long time. That seems to be the way it is. The waiting room is well used.

Everyone seems resigned to the belief that this is the best it can be.

They are not happy about it but they feel powerless to do anything.

Then one day someone demonstrates that it is not the best it can be.

It can be better. A lot better!

And they demonstrate that this better way can be designed.

And they demonstrate that they can learn how to design this better way.

And they demonstrate what happens when they apply their new learning …

… by doing it and by sharing their story of “what-we-did-and-how-we-did-it“.

If life time is so precious, why waste it?

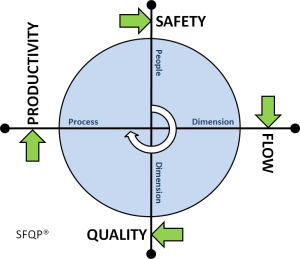

And perhaps the most surprising outcome was that their safer, quicker, calmer design was also 20% more productive.