Have you heard the phrase “Pride comes before a fall“?

Have you heard the phrase “Pride comes before a fall“?

What does this mean? That the feeling of pride is the reason for the subsequent fall?

So by following that causal logic, if we do not allow ourselves to feel proud then we can avoid the fall?

And none of us like the feeling of falling and failing. We are fearful of that negative feeling, so with this simple trick we can avoid feeling bad. Yes?

But we all know the positive feeling of achievement – we feel pride when we have done good work, when our impact matches our intent. Pride in our work.

Is that bad too?

Should we accept under-achievement and unexceptional mediocrity as the inevitable cost of avoiding the pain of possible failure? Is that what we are being told to do here?

The phrase comes from the Bible, from the Book of Proverbs 16:18 to be precise.

And the problem here is that the phrase “pride comes before a fall” is not the whole proverb.

It has been simplified. Some bits have been omitted. And those omissions lead to ambiguity and the opportunity for obfuscation and re-interpretation.

![]()

In the fuller New International Version we see a missing bit … the “haughty spirit” bit. That is another way of saying “over-confident” or “arrogant”.

But even this “authorised” version is still ambiguous and more questions spring to mind:

Q1. What sort of pride are we referring to? Just the confidence version? What about the pride that follows achievement?

Q2. How would we know if our feeling of confidence is actually justified?

Q3. Does a feeling of confidence always precede a fall? Is that how we diagnose over-confidence? Retrospectively? Are there instances when we feel confident but we do not fail? Are there instances when we do not feel confident and then fail?

Q4. Does confidence cause the fall or it is just a temporal association? Is there something more fundamental that causes both high-confidence and low-competence?

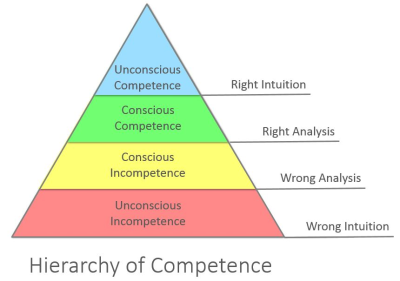

There is a well known model called the Conscious-Competence model of learning which generates a sequence of four stages to achieving a new skill. Such as one we need to achieve our intended outcomes.

We all start in the “blissful ignorance” zone of unconscious incompetence. Our unknowns are unknown to us. They are blind spots. So we feel unjustifiably confident.

In this model the first barrier to progress is “wrong intuition” which means that we actually have unconscious assumptions that are distorting our perception of reality.

What we perceive makes sense to us. It is clear and obvious. We feel confident. We believe our own rhetoric.

But our unconscious assumptions can trick us into interpreting information incorrectly. And if we derive decisions from unverified assumptions and invalid analysis then we may do the wrong thing and not achieve our intended outcome. We may unintentionally cause ourselves to fail and not be aware of it. But we are proud and confident.

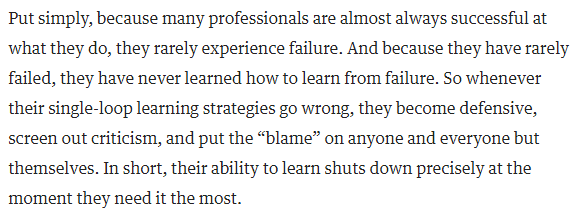

Then the gap between our intent and our impact becomes visible to all and painful to us. So we are tempted to avoid the social pain of public failure by retreating behind the “Yes, But” smokescreen of defensive reasoning. The “doom loop” as it is sometimes called. The Victim Vortex. “Don’t name, shame and blame me, I was doing my best. I did not intent that to happen. To err is human”.

The good news is that this learning model also signposts a possible way out; a door in the black curtain of ignorance. It suggests that we can learn how to correct our analysis by using feedback from reality to verify our rhetorical assumptions. Those assumptions which pass the “reality check” we keep, those which fail the “reality check” we redesign and retest until they pass. Bit by bit our inner rhetoric comes to more closely match reality and the wisdom of our decisions will improve.

And what we then see is improvement. Our impact moves closer towards our intent. And we can justifiably feel proud of that achievement. We do not need to be best-compared-with-the-rest; just being better-than-we-were-before is OK. That is learning.

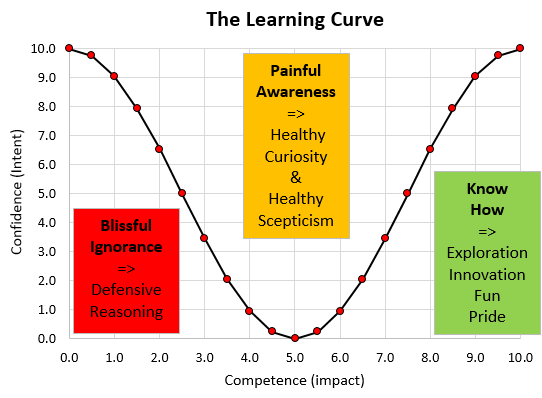

And this is how it feels … this is the Learning Curve … or the Nerve Curve as we call it.

What it says is that to be able to assess confidence we must also measure competence. Outcomes. Impact.

And to achieve excellence we have to be prepared to actively look for any gap between intent and impact. And we have to be prepared to see it as an opportunity rather than as a threat. And we will need to be able to seek feedback and other people’s perspectives. And we need to be to open to asking for examples and explanations from those who have demonstrated competence.

It says that confidence is not a trustworthy surrogate for competence.

It says that we want the confidence that flows from competence because that is the foundation of trust.

Improvement flows at the speed of trust and seeing competence, confidence and trust growing is a joyous thing.

Pride and Joy are OK.

Arrogance and incompetence comes before a fall would be a better proverb.