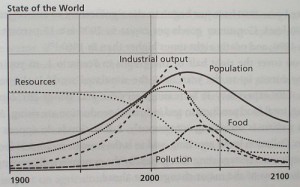

In 1972 a group called the Club of Rome published a report entitled “The Limits to Growth” that examined the possible global impact of our current obsession with competition and growth. They used Jay W Forrester’s computer models described in World Dynamics – models of global stocks and flows of natural resources, capital and people – and explored the range future possibilities based on the best understanding of current reality. Their conclusions were not encouraging – the most likely outcome they predicted if current behaviours continued would be global natural, economic and population collapse before 2100!

In 1972 a group called the Club of Rome published a report entitled “The Limits to Growth” that examined the possible global impact of our current obsession with competition and growth. They used Jay W Forrester’s computer models described in World Dynamics – models of global stocks and flows of natural resources, capital and people – and explored the range future possibilities based on the best understanding of current reality. Their conclusions were not encouraging – the most likely outcome they predicted if current behaviours continued would be global natural, economic and population collapse before 2100!

Their conclusions were discounted by governments, corporations and individuals as doom-preaching but it struck a chord with many and helped to fuel the growth of the global environmental movement.

Thirty years later the original work has been revised, updated and the original predictions compared with actual changes.

The original forecast proved to be prophetic – and revealed an alarming conclusion – that we may already be past the point of no return. It is now forty years since the original work and we have enjoyed the predicted boom years of the 1980’s and ignored the warnings so many options for avoiding a future global collapse have already been squandered. Even if we corrected all the errors of commission and errors of omission today it may be too late because we over-estimate our ability to solve problems and underestimate the effect of “overshoot”.

Suppose you are driving at night in freezing fog and you want to get to your destination as soon as possible so you press on the accelerator and your speed grows. You have not been on this particular road before but you have been driving for years and you trust your experience, skills, and reactions. Suddenly a red light appears out of the gloom – it is a stop light and it is close, too close, so you hit the brakes! You don’t stop immediately though – you are slowing down but not fast enough. The road is slippery, your tyres do not grip as well as usual, and your momentum carries you on. You are burning up the remaining tarmac fast and now you see other lights – white lights – coming from the right. A juggernaut is nearly at the crossroads and it has the green light and is not slowing down. You are on a crash course – and there is nothing you can do – you have no options. The awful realisation dawns that you have made a fatal error of judgement and this is the end as you overshoot the red light and are crushed to a mangled pulp of metal and flesh under the wheels of the juggernaut!

The accident was avoidable – in retrospect. Was it avoidable in prospect? Of course – but only

– IF we were able to challenge our blind trust in our own capability and

– IF we were able to anticipate what could happen and

– IF we had set up trustworthy early warning signals and

– IF we had prepared contingency plans of what we would do if any of the warning bells rang.

Easy enough for an individual to do perhaps – but much more difficult for a group of individuals who have low regard for each other and who are competing to grow bigger and faster. Our mastery of nature has given us the means to change global system dynamics – so our collective fate is sealed by our collective behaviour. We have the ability to achieve mutually assured destruction (MAD) without dropping a single bomb – and we are on course to do so not because we set out to – but because we did not set out not to. The error of omission is the stealth killer.

Is this global disaster scenario realistic? Is there anything that can be done? Are we collectively capable of doing it? The evidence suggests “yes” to all three questions – there is hope – but it will require a paradigm shift in thinking rather than a breakthrough in technology.

The laws of physics will seal our fate unless the laws of people adapt – and it may already be too late to avoid some degree of catastrophic decline – which implies billions of lives will be lost needlessly. Those of us in positions of most influence are already to old to expect to live to see the fruits of our collective error of omission – our children will bear the pain of our ignorance and arrogance. What do you want carved on your gravestone … “Here lies X – who saw but did not act. Sorry.”

Limits to Growth – the 30 year update. ISBN 978-1-84407-144-9