The Nerve Curve is the emotional roller-coaster ride that everyone who engages in Improvement needs to become confident to step onto.

The Nerve Curve is the emotional roller-coaster ride that everyone who engages in Improvement needs to become confident to step onto.

Just like a theme park ride it has ups and downs, twists and turns, surprises and challenges, an element of danger and a splash of excitement. If it did not have all of those components then it would not be fun and there would not be queues of people wanting to ride, again and again. And the reason that theme parks are so successful is because their rides have been very carefully designed – to be challenging, exciting, fun and safe – all at the same time.

So, when we challenge others to step aboard our Improvement Nerve Curve then we need to ensure that our ride is safe – and to do that we need to understand where the emotional dangers lurk, to actively point them out and then avoid them.

A big danger hides right at the start. To get aboard the Nerve Curve we have to ask questions that expose the Elephant-in-the-Room issues. Everyone knows they are there – but no one wants to talk about them. The biggest one is called Distrust – which is wrapped up in all sorts of different ways and inside the nut is the Kernel of Cynicism. The inexperienced improvement facilitator may blunder straight into this trap just by using one small word … the word “Why”? Arrrrrgh! Kaboom! Splat! Game Over.

The “Why” question is like throwing a match into a barrel of emotional gunpowder – because it is interpreted as “What is your purpose?” and in a low-trust climate no one will want to reveal what their real purpose or intention is. They have learned from experience to keep their cards close to their chest – it is safer to keep agendas hidden.

A much safer question is “What?” What are the facts? What are the effects? What are the causes? What works well? What does not? What do we want? What don’t we want? What are the constraints? What are our change options? What would each deliver? What are everyone’s views? What is our decision? What is our first action? What is the deadline?

Sticking to the “What” question helps to avoid everyone diving for the Political Panic Button and pulling the Emotional Emergency Brake before we have even got started.

The first part of the ride is the “Awful Reality Slope” that swoops us down into “Painful Awareness Canyon” which is the emotional low-point of the ride. This is where the elephants-in-the-room roam for all to see and where passengers realise that, once the issues are in plain view, there is no way back.

The next danger is at the far end of the Canyon and is called the Black Chasm of Ignorance and the roller-coaster track goes right to the edge of it. Arrrgh – we are going over the edge of the cliff – quick grab the Wilful Blindness Goggles and Denial Bag from under the seat, apply the Blunder Onwards Blind Fold and the Hope-for-the-Best Smoke Hood.

So, before our carriage reaches the Black Chasm we need to switch on the headlights to reveal the Bridge of How: The structure and sequence that spans the chasm and that is copiously illuminated with stories from those who have gone before. The first part is steep though and the climb is hard work. Our carriage clanks and groans and it seems to take forever but at the top we are rewarded by a New Perspective and the exhilarating ride down into the Plateau of Understanding where we stop to reflect and to celebrate our success.

Here we disembark and discover the Forest of Opportunity which conceals many more Nerve Curves going off in all directions – rides that we can board when we feel ready for a new challenge. There is danger lurking here too though – hidden in the Forest is Complacency Swamp – which looks innocent except that the Bridge of How is hidden from view. Here we can get lured by the pungent perfume of Power and the addictive aroma of Arrogance and we can become too comfortable in the Zone. As we snooze in the Hammock of Calm from we do not notice that the world around us is changing. In reality we are slipping backwards into Blissful Ignorance and we do not notice – until we suddenly find ourselves in an unfamiliar Canyon of Painful Awareness. Ouch!

Being forewarned is our best defense. So, while we are encouraged to explore the Forest of Opportunity, we learn that we must also return regularly to the Plateau of Understanding to don the Habit of Humility. We must regularly refresh ourselves from the Fountain of New Knowledge by showing others what we have learned and learning from them in return. And when we start to crave more excitement we can board another Nerve Curve to a new Plateau of Understanding.

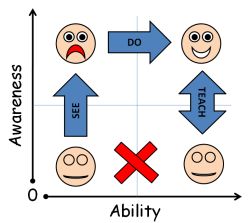

The Safety Harness of our Improvement journey is called See-Do-Teach and the most important part is Teach. Our educators need to have more than just a knowledge of how-to-do, they also need to have enough understanding to be able to explore the why-to -do. The Quest for Purpose.

The Safety Harness of our Improvement journey is called See-Do-Teach and the most important part is Teach. Our educators need to have more than just a knowledge of how-to-do, they also need to have enough understanding to be able to explore the why-to -do. The Quest for Purpose.

To convince others to get onboard the Nerve Curve we must be able to explain why the Issues still exist and why the current methods are not sufficient. Those who have been on the ride are the only ones who are credible because they understand. They have learned by doing.

And that understanding grows with practice and it grows more quickly when we take on the challenge of learning how to explore purpose and explain why. This is Nerve Curve II.

All aboard for the greatest ride of all.