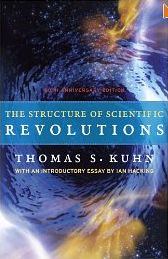

In 1628 a courageous and paradigm shifting act happened. A small 72-page book was published in Frankfurt that openly challenged 1500 years of medical dogma. The book challenged the authority of Galen (129-200) the most revered medical researcher of antiquity and Hippocrates (460 BC – 370 BC) the Father of Medicine.

The writer of the book was a respected and influential English doctor called William Harvey (1578-1657) who was physician to King James I and who became personal physician to King Charles I.

William Harvey was from yeoman stock. The salt-of-the-earth. Loyal, honest and hard-working free men often owned their land – but who were way down the social pecking order. They were the servant class.

William Harvey was from yeoman stock. The salt-of-the-earth. Loyal, honest and hard-working free men often owned their land – but who were way down the social pecking order. They were the servant class.

William was the eldest son of Thomas Harvey from Folkstone who had a burning ambition to raise the station of his family from yeoman to gentry. This implied that the family was allowed to have their own coat of arms. To the modern mind this is almost meaningless – in the 17th Century it was not!

And Thomas was wealthy enough to have William formally educated and the dutiful William worked hard at his studies and was rewarded by gaining a place at Caius College in Cambridge University. John Caius (1510-1573) was a physician who had studied in Padua, Italy – the birthplace of modern medicine. William did well and after graduating from Cambridge in 1597 he too travelled through Europe to study in Padua. There he saw Galenic dogma challenged and defused using empirical evidence. This was at the same time that Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) was challenging the geocentric dogma of the Catholic Church using empirical evidence gained by simple celestial observation with his new telescope. This was the Renaissance. The Rebirth of Learning. This was the end of the Dark Ages of Dogma.

Harvey brought this “new thinking” back to Elizabethan England and decided to focus his attention on the heart. And what Harvey discovered was that the accepted truth from the ancients about how the heart worked was wrong. Galen was wrong. Hippocrates was wrong.

But this was not the most interesting part of the story. It was the how he proved it that was radically different. He used evidence from reality to disprove the rhetoric. He used the empirical method espoused by Francis Bacon (1561-1626): what we now call the Scientific Method. In effect what Harvey said was “If you do not believe or agree with me then all you need to do is repeat the observation yourself. Do an autopsy“. [aut=self and opsy=see]. William Harvey saw and conducted human dissection in Padua, and practiced both it and animal vivisection back in England – and by that means he discovered how the heart actually worked.

Harvey opened a crack in the cultural ice that had frozen medical innovation for 1500 years. The crack in the paradigm was a seed of doubt planted by a combination of curiosity and empirical experimentation:

Q1: If Galen was wrong about the heart then what else was he wrong about? The Four Humours too?

Q2: If the heart is just a simple pump then where does the Spirit reside?

Looking back with our 21st century perspective these are meaningless questions. To a person in the 17th Century these were fundamental paradigm-challenging questions. They rocked the whole foundation of their belief system. The believed that illness was a natural phenomenon and was not caused by magic, curses and evil spirits; but they believed that celestial objects, the stars and planets, were influential. In 1628 astronomy and astrology were the same thing.

And Harvey was savvy. He was both religious and a devout Royalist and he knew that he would need the support of the most powerful person in England – the monarch. And he knew that he needed to be a respectable member of a powerful institution – the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) which he gained in 1604. A remarkable achievement in itself for someone of yeoman stock. With this ticket he was able to secure a position at St Bartholomew’s Hospital in Smithfield, London and in 1615 he became the RCP Lumleian Lecturer which involved lecturing on anatomy – which he did from 1616. By virtue of his position Harvey was able to develop a lucrative private practice in London and by that route was introduced to the Court. In 1618 he was appointed as Physician Extraordinary to King James I. [The Physician Ordinary was the top job].

And even with this level of influence, credibility and royal support his paradigm-challenging message met massive cultural and political resistance because he was challenging a 1500 year old belief.

Over the 12 years between 1616 and 1628 Harvey invested a lot of time sharing his ideas and the evidence with influential friends and he used their feedback to deepen his understanding, to guide his experiments, and to sharpen his arguments. He had learned how to debate at school and had developed his skill at Cambridge so he know how to turn argments-against into arguments-for.

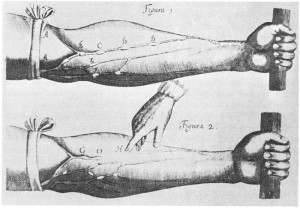

Harvey was intensely curious, he knew how to challenge himself, to learn, to influence others, and to change their worldview. He knew that easily observable phenomemon could help spread the message – such as the demonstration of venous valves in the arm illustrated in his book.

After the publication of De Motu Cordis in 1628 his personal credibility and private practice suffered massively because as a self-declared challenger of the current paradigm he was treated with skepticism and distrust by his peers. Gossip is effective.

After the publication of De Motu Cordis in 1628 his personal credibility and private practice suffered massively because as a self-declared challenger of the current paradigm he was treated with skepticism and distrust by his peers. Gossip is effective.

And even with all his passion, education, evidence, influence and effort it still took 20 years for his message to become widely enough accepted to survive him. And it did so because others resonated with the message; others like a Rene Descartes (1596-1650).

William Harvey is now remembered as one of the founders of modern medical science. When he published De Motu Cordis he triggered a paradim shift – one that we take for granted today. Harvey showed that the path to improvement is through respectfully challenging accepted dogma with a combination of curiosity, humility, hard-work, and empirical evidence. Reality reinforced rhetoric.

Today we are used to having the freedom of speech and we are familiar with using experimental data to test our hypotheses. In 1628 this was new thinking and was very risky. People were burned at the stake for challenging the authority of the Catholic Church and the Holy Roman Inquisition was still active well into the 18th Century!

Harvey was also innovative in the use of arithmetic. He showed that the volume of blood pumped by the heart in a day was far more than the liver could reasonably generate. But at that time arithmetic was the domain of merchants, accountants and money-lenders and was not seen as a tool that a self-respecting natural philosopher would use! The use of mathematics as a scientific tool did not really take off until after Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727) published the Principia in 1687 – 30 years after Harvey’s death. [To read more about William Harvey click here].

William Harvey was an Improvementologist.

So what lessons can modern Improvement Scientists draw from his story?

- The first is that all significant challanges to current thinking will meet emotional and political resistance. They will be discounted and ridiculed because they challenge the authority of experts.

- The second is that challenges must be made respectfully. The current thinking has both purpose and value. Improvements build on the foundation of knowledge and only challenge what is not fit for purpose.

- The third is that the challenge must be more than rhetorical – it must be backed with replicatable evidence. A difference of opinion is just that. Reality is the ultimate arbiter.

- The fourth is that having an idea is not enough – testig, proving, explaining and demonstrating are needed too. It is hard work to change a mental paradigm and it requires an emotionally secure context to do it. People who are under pressure will find it more difficult and more traumatic.

- The fifth is that patience and persistence are needed. Worldview change takes time and happen in small steps. The new paradigm needs to find its place.

And Harvey did not say that Galen and Hippocrates were completely wrong – just partly wrong. And he explained that the reason that Hippocrates and Galen could not test their ideas about human anatomy was because dissection of human bodies was illegal in Greek and Roman societies. Padua in Renaissance Italy was one of the first places where dissection was permitted by Law.

So which part of the Galenic dogma did Harvey challenge?

He challenged the dogma that blood was created continuously by the liver. He challenged the dogma that there were invisible pores between the right and left sides of the heart. He challenged the dogma that the arteries ‘sucked’ the blood from the heart. He challenged the dogma that the ‘vitalised’ arterial blood was absorbed by the tissues. And he challenged these beliefs with empirical evidence. He showed evidence that the blood circulated fom the right heart to the lungs to the left heart to the body and back to the right heart. He showed evidence that the heart was a muscular pump. And he showed evidence that it worked the same way in man and in animals.

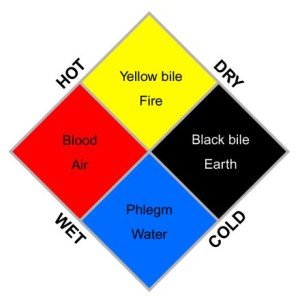

In so doing he undermined the foundation of the whole paradigm of ancient belief that illness was the result of an imbalance between the Four Humours. Yellow Bile (associated with the liver), Black Bile (associated with the Spleen), Blood (as ociated with the heart) and Phlegm (associated with the lungs).

In so doing he undermined the foundation of the whole paradigm of ancient belief that illness was the result of an imbalance between the Four Humours. Yellow Bile (associated with the liver), Black Bile (associated with the Spleen), Blood (as ociated with the heart) and Phlegm (associated with the lungs).

We still have the remnants of this ancient belief in our language. The Four Humours were also associated with Four Temperaments – four observable personality types. The phlegmatic type (excess phlegm), the sanguine type (excess blood), the choleric type (excess yellow bile), and the melancholic type (excess black bile).

We still talk about “the heart of the matter” and being “heartless”, “heartfelt” and “change of heart” because the heart was believed to be where emotion and passion resided. Sanguine is the term given to people who show warmth, passion, a live-now-pay-later, optimistic and energetic disposition. And this is not an unreasonable hypothesis given that we are all very aware of changes in how our heart beats when we are emotionally aroused; and how the color of our skin changes.

So when Harvey suggested that blood flowed in a circle from the heart to the arteries and back to the heart via the veins; and that the heart was just a pump then this idea shook the current paradigm on many levels – right down to its roots.

And the ancient justification for a whole raft of medical diagnoses, prognoses and treatments was challenged. The House of Cards was challenged. And many people owed their livelihoods to these ancient beliefs – so it is no surprise that his peers were not jumping for joy to hear what Harvey said.

But Harvey had reality on his side – and reality trumps rhetoric.

And the same is true today, 500 years later.

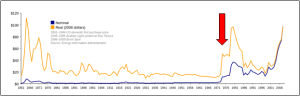

The current paradigm is being shaken. The belief that we can all live today and pay tomorrow. The belief that our individual actions have no global impact and no long lasting consequences. The belief that competition is the best route to contentment.

The evidence is accumulating that these beliefs are wrong.

The difference is that today the paradigm is being challenged by a collective voice – not by a lone voice.

Subscribe: [smlsubform]

L: U

L: U