The recurring theme this week has been safety and risk.

The recurring theme this week has been safety and risk.

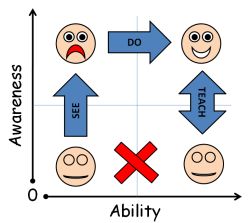

Specifically in a healthcare context. Most people are not aware just how risky our current healthcare systems are. Those who work in healthcare are much more aware of the dangers but they seem powerless to do much to make their systems safer for patients.

The shroud-waving zealots who rant on about safety often use a very unhelpful quotation. They say “Every system is perfectly designed to deliver the performance it does“. The implication is that when the evidence shows that our healthcare systems are dangerous …. then …. we designed them to be dangerous. The reaction from the audience is emotional and predictable “We did not intend this so do not try to pin the blame on us!” The well-intentioned shroud-waving safety zealot loses whatever credibility they had and the collective swamp of cynicism and despair gets a bit deeper.

The warning-word here is design – because it has many meanings. The design of a system can mean “what the system is” in the sense of a blueprint. The design of a system can also mean “how the blueprint was created”. This process sense is the trap – because it implies intention. Design needs a purpose – the intended outcome – so to say an unsafe system has been designed is to imply that it was intended to be unsafe. This is incorrect.

The message in the emotional backlash that our well-intended zealot provoked is “You said we intended bad things to happen which is not correct so if you are wrong on that fundamental belief then how can I trust anything else you say?“. This is the reason zealots lose credibility and actually make improvement less likely to happen.

The reality is not that the system was designed to be unsafe – it is that it was not designed not to be. The double negatives are intentional. The two statements are not the same.

The default way of the Universe is evolutionary (which is unintentional and reactive) and chaotic (which is unstable and unsafe). To design a system to be not-unsafe we need to understand Two Sciences – Design Science and Safety Science. Only then can we proactively and intentionally design safe, stable, and trustable systems. If we do nothing and do not invest in mastering the Two Sciences then we will get the default outcome: unintended unsafety. This is what the uncomfortable evidence says we have.

So where does the Frightening Cost of Fear come in?

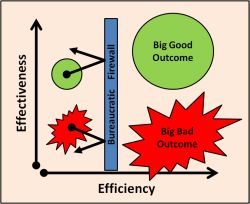

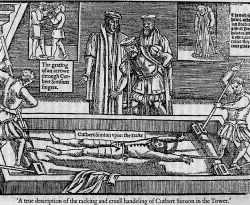

If our system is unintentionally and unpredictably unsafe then of course we will try to protect ourselves from the blame which inevitably will follow from disappointed customers. We fear the blame partly because we know it is justified and partly because we feel powerless to avoid it. So we cover our backs. We invent and implement complex check-and-correct systems and we document everything we do so that we have the evidence in the inevitable event of a bad outcome and the backlash it unleashes. The evidence that proves we did our best; it shows we did what the safety zealots told us to do; it shows that we cannot be held responsible for the bad outcome.

Unfortunately this strategy does little to prevent bad outcomes. In fact it can have has exactly the opposite effect of what is intended. The added complexity and cost of our cover-my-back bureaucracy actually increases the stress and chaos and makes bad outcomes more likely to happen. It makes the system even less safe. It does not deflect the blame. It just demonstrates that we do not understand how to design a not-unsafe system.

And the financial cost of our fear is frighteningly high.

And the financial cost of our fear is frighteningly high.

Studies have shown that over 60% of nursing time is spent on documentation – and about 70% of healthcare cost is on hospital nurse salaries. The maths is easy – at least 42% of total healthcare cost is spent on back-covering-blame-deflection-bureaucracy.

It gets worse though.

Those legal documents called clinical records need to be moved around and stored for a minimum of seven years. That is expensive. Converting them into an electronic format misses the point entirely. Finding the few shreds of valuable clinical information amidst the morass of back-covering-bureaucracy uses up valuable specialist time and has a high risk of failure. Inevitably the risk of decision errors increases – but this risk is unmeasured and is possibly unmeasurable. The frustration and fear it creates is very obvious though: to anyone willing to look.

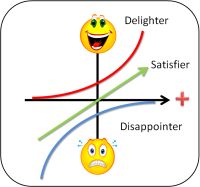

The cost of correcting the Niggles that have been detected before they escalate to Not Agains, Near Misses and Never Events can itself account for half the workload. And the cost of clearing up the mess after the uncommon but inevitable disaster becomes built into the system too – as insurance premiums to pay for future litigation and compensation. It is no great surprise that we have unintentionally created a compensation culture! Patient expectation is rising.

Add all those costs up and it becomes plausible to suggest that the Cost of Fear could be a terrifying 80% of the total cost!

Of course we cannot just flick a switch and say “Right – let us train everyone in safe system design science“. What would all the people who make a living from feeding on the present dung-heap do? What would the checkers and auditors and litigators and insurers do to earn a crust? Join the already swollen ranks of the unemployed?

If we step back and ask “Does the Cost of Fear principle apply to everything?” then we are faced with the uncomfortable conclusion that it most likely is. So the cost of everything we buy will have a Cost of Fear component in it. We will not see it written down like that but it will be in there – it must be.

This leads us to a profound idea. If we collectively invested in learning how to design not-unsafe systems then the cost of everything could fall. This means we would not need to work as many hours to earn enough to pay for what we need to live. We could all have less fear and stress. We could all have more time to do what we enjoy. We could all have both of these and be no worse off in terms of financial security.

This leads us to a profound idea. If we collectively invested in learning how to design not-unsafe systems then the cost of everything could fall. This means we would not need to work as many hours to earn enough to pay for what we need to live. We could all have less fear and stress. We could all have more time to do what we enjoy. We could all have both of these and be no worse off in terms of financial security.

This Win-Win-Win outcome feels counter-intuitive enough to deserve serious consideration.

So here are some other blog topics on the theme of Safety and Design:

Never Events, Near Misses, Not Agains and Nailing Niggles

The One Big Whack can come at the start and is a shock tactic designed to generate an emotional flip – a Road to Damascus moment – one that people remember very clearly. This is the stuff that newspapers fall over themselves to find – the Big Front Page Story – because it is emotive so it sells newspapers. The One Big Whack can also come later – as an act of desperation by those in power who originally broadcast The Big Idea and who are disappointed and frustrated by lack of measurable improvement as the time ticks by and the money is consumed.

The One Big Whack can come at the start and is a shock tactic designed to generate an emotional flip – a Road to Damascus moment – one that people remember very clearly. This is the stuff that newspapers fall over themselves to find – the Big Front Page Story – because it is emotive so it sells newspapers. The One Big Whack can also come later – as an act of desperation by those in power who originally broadcast The Big Idea and who are disappointed and frustrated by lack of measurable improvement as the time ticks by and the money is consumed.