The world seems to is getting itself into a real flap at the moment.

The world seems to is getting itself into a real flap at the moment.

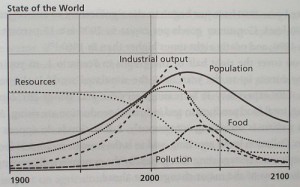

The global economy is showing signs of faltering – the perfect dream of eternal financial growth seems to be showing cracks and is increasingly looking tarnished.

The doom mongers are surprisingly quiet – perhaps because they do not have any new ideas either.

It feels like the system is heading for a big flop and that is not a great feeling.

Last week I posed the Argument-Free-Problem-Solving challenge – and some were curious enough to have a go. It seems that the challenge needs more explanation of how it works to create enough engagement to climb the skepticism barrier.

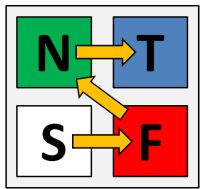

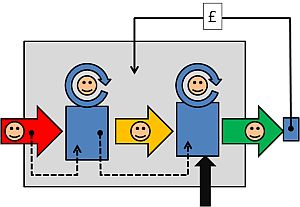

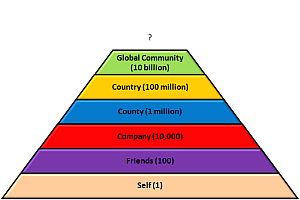

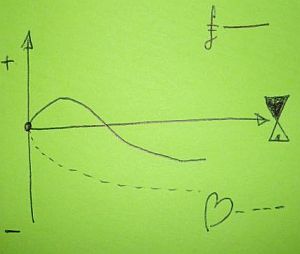

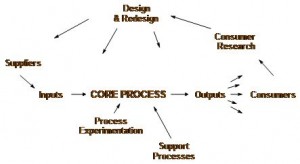

At the heart of the AFPS method is The 4N Chart® – a simple, effective and efficient way to get a balanced perspective of the emotional contours of the change terrain. The improvement process boils down to recognising, celebrating, and maintaining the Nuggets, flipping the Niggles into NoNos and reinvesting the currencies that are released into converting NiceIfs into more Nuggets.

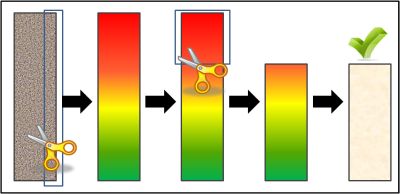

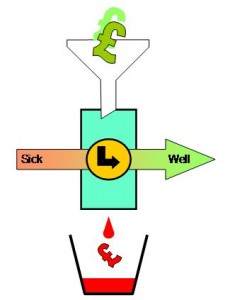

The trick is the flip.

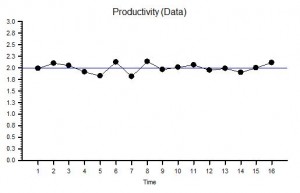

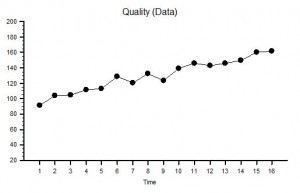

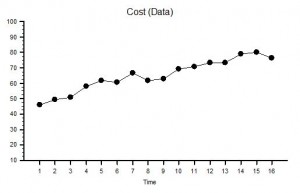

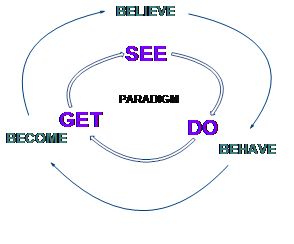

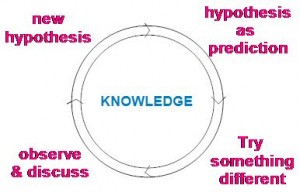

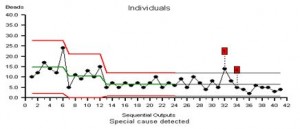

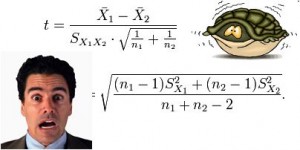

To perform a flip we have to make our assumptions explicit – which means we have to use external reality to challenge our internal rhetoric. We need real data – presented in an easily digestible format – as a picture – and in context which converts the data into information that we can then ingest and use to grow our knowledge and broaden our understanding.

To convert knowledge into understanding we must ask a question: “Is our assumption a generalisation from a specific experience?”

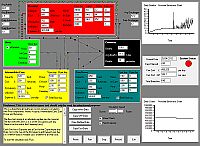

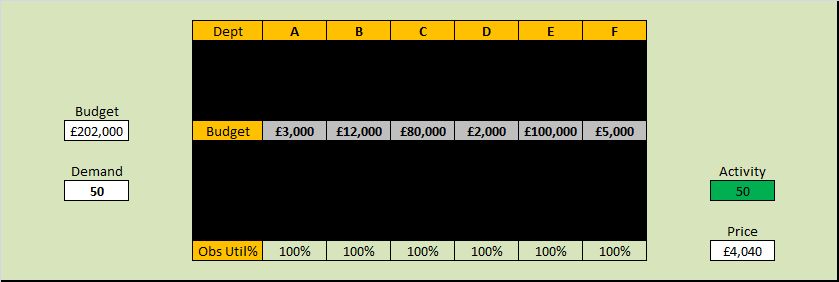

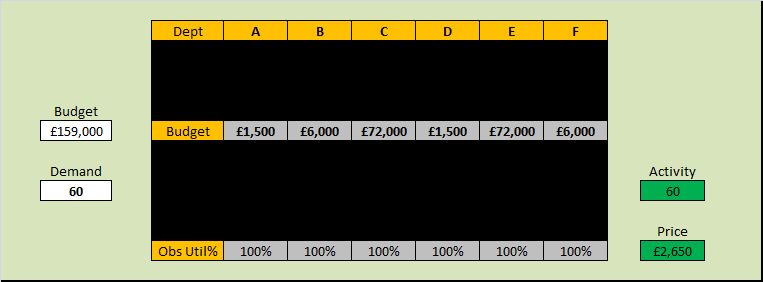

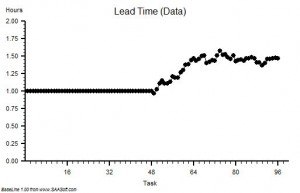

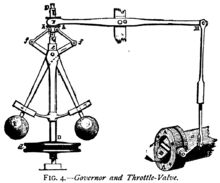

For example – it is generally assumed that high utilisation is associated with high productivity – and we want high productivity so we push for high utilisation. And if we look at reality we can easily find evidence to support our assumption. If I have under-utilised fixed-cost resources and I push more work into the process, I see an increase the flow in the stream, and an increase in utilisation, and an increase in revenue, and no increase in cost – higher outcome: higher productivity.

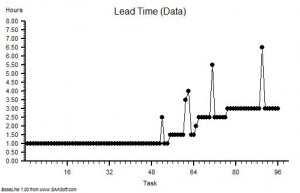

But if we look more carefully we can also find examples that seem to disprove our assumption. I have under-utilised resources and I push more work into the process, and the flow increases initially then falls dramatically, the revenue falls, productivity falls and when I look at all my resources they are still fully utilised. The system has become gridlocked – and when I investigate is discover that the resource I need to unlock the flow is tied up somewhere else in the process with more urgent work. My system does not have an anti-deadlock design.

Our rhetoric of generalisation has been challenged by the reality of specifics – and it only takes one example. One black swan will disprove the generalisation that “all swans are white”.

We now know we need to flip the “general assumption” into “specific evidence” – changing the words “all”, “always”, “none” and “never” into “some” and “sometimes”.

In our example we flip our assumption into “sometimes utilisation and productivity go up together, and sometimes they do not”. This flip reveals a new hidden door in the invisible wall that limits the breadth of our understanding and that unconsciously hinders our progress.

To open that door we must learn how to tell one specific from another and opening that door will lead to a path of discovery, more knowledge, broader understanding, deeper wisdom, better decisions, more effective actions and sustained improvement.

Flap-Flop-Flip.

This week has seen the loss of one of the greatest Improvement Scientists – Steve Jobs – creator of Apple – who put the essence of Improvement Science into words more eloquently than anyone in his 2005 address at Stanford University.

“Your time is limited, so don’t waste it living someone else’s life. Don’t be trapped by dogma – which is living with the results of other people’s thinking. Don’t let the noise of other’s opinions drown out your own inner voice. And most important, have the courage to follow your heart and intuition. They somehow already know what you truly want to become. Everything else is secondary.” Steve Jobs (1955-2011).

And with a lifetime of experience of leading an organisation that epitomises quality by design Steve Jobs had the most credibility of any person on the planet when it comes to management of improvement.