There are two broad approaches to improvement. One is to start with what we have got now and tinker with it in the hope it will get better. When this is done well it is effective albeit slow. When it is done badly it amounts to dangerous meddling. The more interconnected the system we are trying to improve the more likely our well intentioned tinkering will create a bigger problem in the future than we have now.

There are two broad approaches to improvement. One is to start with what we have got now and tinker with it in the hope it will get better. When this is done well it is effective albeit slow. When it is done badly it amounts to dangerous meddling. The more interconnected the system we are trying to improve the more likely our well intentioned tinkering will create a bigger problem in the future than we have now.

Another approach is to start with what-we-want-to-have in the future and then design-to-deliver it. Our starting point is not an aspirational dream vision, also known as an hallucination, it is a clear performance specification with four dimensions: safety, delivery, quality and affordability. This is called a SFQP specification.

The first one to focus on is safety … and what we usually find is that risk of harm is usually a knock-on effect of delivery and quality design problems.

The easiest one is delivery – because it is the application of process physics. The next easiest one is affordability because that is the application of value system accounting.

The tricky one is quality because that implies subjectivity, people, psychology, behaviour and politics. When we add quality to our design challenge we rack up the wickedness score!

So, how do we create a clear and realistic output quality performance specification?

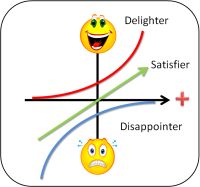

If we draw up a chart with Subjective Quality on the Y-axis and Objective Performance on the X-axis, we can plot all the characteristics of our current and future design on this chart. And when we do that we discover some surprising things.

First – some factors go unnoticed until the performance drops. Said another way we do not notice when it is working – we only only notice when it is not. These factors are called Disappointers. We take for granted that things work 99% of the time – the sun comes up every morning; there is 21% of oxygen in the atmosphere; the air temperature is OK; the electricity is on; the milk, paper and post gets delivered; the car starts and so on. We take it all for granted and we complain when it unexpectedly does not.

First – some factors go unnoticed until the performance drops. Said another way we do not notice when it is working – we only only notice when it is not. These factors are called Disappointers. We take for granted that things work 99% of the time – the sun comes up every morning; there is 21% of oxygen in the atmosphere; the air temperature is OK; the electricity is on; the milk, paper and post gets delivered; the car starts and so on. We take it all for granted and we complain when it unexpectedly does not.

So if we ask our customers what they want from an improved service they do not spontaneously volunteer what is currently working well and that they take for granted – because it is out of their awareness. This is what Henry Ford implied when he said “If I asked the customer what they wanted I would have got a faster horse“. It is also the reason why a Three Wins design starts with The 4N Chart® – and specifically the Nuggets corner. We need to make conscious what works well because when we plan improvement we do not want to unintentionally discard the baby with the bath water!

Second – some factors go unnoticed until performance exceeds a minimum threshold. They are not expected so we do not mind if they are not provided – but if they are unexpectedly provided then we are surprised and Delighted. The first time. Once we know what is possible we come to expect it again, and eventually every time.

A common design error is to try to use a Delighter to compensate for a Disappointer.

Suppose we walked into our hotel room and found a complimentary bottle of wine that we were not expecting and then we discovered that there was no toilet paper and the shower was cold. The bottle of wine would not compensate for our disappointment and it might even irritate us because we conclude that the management does not care about our basic needs. Our trust is eroded and our feedback reflects that.

Effective design for trusted quality starts by eliminating the possibility of disappointment. We design it so the expected essentials are “right first time and every time“. Our measure of success is not praise – it is absence of complaints. A deafening silence. It is what does not happen that is important. Good expected essential design is invisible – because it never intrudes on our awareness. And for this reason it is surprisingly difficult to do. It requires pro-action not re-action.

Effective design for trusted quality starts by eliminating the possibility of disappointment. We design it so the expected essentials are “right first time and every time“. Our measure of success is not praise – it is absence of complaints. A deafening silence. It is what does not happen that is important. Good expected essential design is invisible – because it never intrudes on our awareness. And for this reason it is surprisingly difficult to do. It requires pro-action not re-action.

The third type of factor is the Satisfier – and these are the ones that our customers will volunteer because they are aware of them. Lower performance giving lower perceived quality scores and higher performance giving higher. These are the “you get what you pay for” factors. A better designed car is expected to be more comfortable, quieter, easier to drive, safer, more reliable, more effort-saving gadgets and so on. Price is a satisfier. Cost is not. Cost is an output of the design process. So the better the design the greater the gap can be between cost and price.

This method is called Kano Analysis and an understanding of it is essential for effective quality improvement. And like so much of Improvement Science it appears counter-intuitive at first, common-sense when explained, and blindingly obvious when experienced.