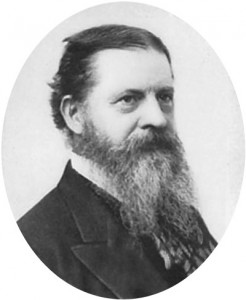

The term Pragmatist is a modern one – it was coined by Charles Sanders Pierce (1839-1914) – a 19th century American polymath and iconoclast. In plain speak he was a tree-shaker and a dogma-breaker; someone who regarded rules created by people as an opportunity for innovation rather than a source of frustration.

The term Pragmatist is a modern one – it was coined by Charles Sanders Pierce (1839-1914) – a 19th century American polymath and iconoclast. In plain speak he was a tree-shaker and a dogma-breaker; someone who regarded rules created by people as an opportunity for innovation rather than a source of frustration.

A tree-shaker reframes the Three Fears that block change and improvement; the Fear of Ambiguity; the Fear of Ridicule and the Fear of Failure. A tree-shaker re-channels their emotional energy from fear into innovation and exploration. They feel the fear but they do it anyway. But how do they do it?

To understand this we first need to explore how we learn to collectively suppress change by submitting to peer-fear.

In the 1960’s there was an experiment done with Rhesus monkeys that sheds light on a possible mechanism: the monkeys appeared to learn from each other by observing the emotional responses of other monkeys to threats. The story of the Five Monkeys and the Banana Experiment first appeared in a management textbook in 1996 but there is no evidence that this particular experiment was ever performed. With this in mind here is a version of the story:

Five naive monkeys were offered a banana but it required climbing a ladder to get it. Monkeys like bananas and are good at climbing. The ladder was novel. And every time any of the monkeys started to climb the ladder all the monkeys were sprayed with cold water. Monkeys do not like cold water. It was a classic conditioning experiment and after just a few iterations the monkeys stopped trying to climb the ladder to get the banana. They had learned to fear the ladder and their natural desire for the banana was suppressed by their new fear: a learned association between climbing the ladder and the unpleasant icy shower. Next the psychologists replaced one of the monkeys with a new naive monkey – who immediately started to climb the ladder to get the banana.

Five naive monkeys were offered a banana but it required climbing a ladder to get it. Monkeys like bananas and are good at climbing. The ladder was novel. And every time any of the monkeys started to climb the ladder all the monkeys were sprayed with cold water. Monkeys do not like cold water. It was a classic conditioning experiment and after just a few iterations the monkeys stopped trying to climb the ladder to get the banana. They had learned to fear the ladder and their natural desire for the banana was suppressed by their new fear: a learned association between climbing the ladder and the unpleasant icy shower. Next the psychologists replaced one of the monkeys with a new naive monkey – who immediately started to climb the ladder to get the banana.  What happened next is interesting. The other four monkeys pulled the new monkey back. They did not want to get another cold shower. After a while the new monkey learned because his fear of social rejection was greater than his desire for the banana. He stopped trying to get the banana. This cycle was repeated four more times until all the original monkeys had been replaced. None of the five remaining monkeys had any personal experience of the cold shower – but the ladder-avoiding behaviour remained and was enforced by the group, even though the original reason for shunning the ladder was unknown.

What happened next is interesting. The other four monkeys pulled the new monkey back. They did not want to get another cold shower. After a while the new monkey learned because his fear of social rejection was greater than his desire for the banana. He stopped trying to get the banana. This cycle was repeated four more times until all the original monkeys had been replaced. None of the five remaining monkeys had any personal experience of the cold shower – but the ladder-avoiding behaviour remained and was enforced by the group, even though the original reason for shunning the ladder was unknown.

Here is the quoted reference to the experiment on which the story is based.

Stephenson, G. R. (1967). Cultural acquisition of a specific learned response among rhesus monkeys. In: Starek, D., Schneider, R., and Kuhn, H. J. (eds.), Progress in Primatology, Stuttgart: Fischer, pp. 279-288.

So it would appear that a very special type of monkey would be needed to break a culturally enforced behavioural norm. One that is curious, creative and courageous, and one that does not fear ridicule or failure. One that is immune to peer-fear.

We could extrapolate from this story and reflect on how peer pressure might impede change and improvement in the workplace. When well-intended, innocent, creativity and innovation are met with the emotional ice-bath of dire warnings, criticism, ridicule and cynicism then the unconfident innovator may eventually give up trying and start to believe that improvement is impossible. The Hans Christian Anderson’s short tale of the Emporer’s New Clothes is a well known example – the one innocent child says what all the experienced adults have learned to deny. A culture of peer-fear can become self-sustaining and this change-avoiding-culture appears to be a common state of affairs in many organisations; in particular ones of an academic and bureaucratic leaning.

At the other end of the change spectrum from Bureaucracy sits Chaos. It is also resisted but the behaviour is fuelled by a different fear – the Fear of Ambiguity. We prefer the known and the predictable. We follow ingrained habits. We prevaricate even when our rationality says we should change. We dislike the feeling of ambiguity and uncertainty because it leaves us with a sense of foreboding and dread. Change is strongly associated with confusion and we appear hard-wired to avoid it. Except that we are not. This is learned behaviour and we learned it when we were very young. As adults we reinforce it; as adults we replicate it; and as adults impose it on others – including our next generation. The generation that will inherit our world and who will look after us when we are old and frail. We will reap what we sow. But if we learned it and teach it then are we able to unlearn it and unteach it?

Enter the Pragmatists. They have learned to harness the Three Fears. Or rather they have unlearned their association of Fear with Change. Sometimes this unlearning came from a crisis – they were forced to change by external factors. Doing nothing was not an option. Sometimes their unlearning came from inspiration – they saw someone else demonstrate that other options were possible and beneficial. Sometimes their insight came by surprise – an unexpected change of perspective exposed the hidden opportunity. An eureka moment.

Whatever the route the Pragmatist discovers a new tool: a tool labelled “Heuristics”. A heuristic is a “rule of thumb” – an empirically derived good-enough-for-now guideline. Heuristics include some uncertainty, some ambiguity and some risk. Just enough uncertainty and ambiguity to build a flexible conceptual framework that is strong enough, resilient enough and modifiable enough to facilitate learning and improvement. And with it a pinch of risk to spice the sauce – because we all like a bit of risk.

The Improvement Scientist is a Pragmatist and a Practitioner of Heuristics – both of which can be learned.