There is a common, and often fatal, organisational disease called “egomatosis”.

It starts as a swelling of the Egocentre in the Executive Organ that is triggered by a deficiency in the Humility Feedback Loop (HFL), which in turn is linked to underdevelopment or dysfunction of the phonic sensory input system – selective deafness.

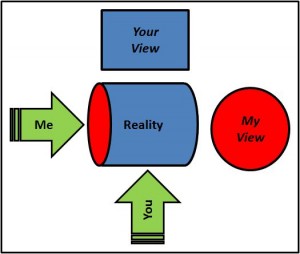

Unfortunately, the Egocentre is located next to other perception centres – specifically insight – so as the egoma develops the visual perception also becomes progressively distorted until a secondary cultural blind-spot develops.

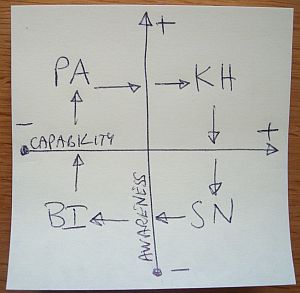

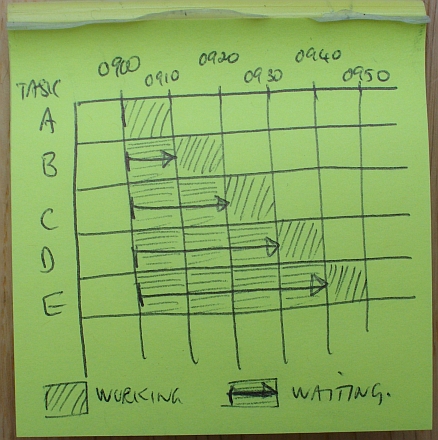

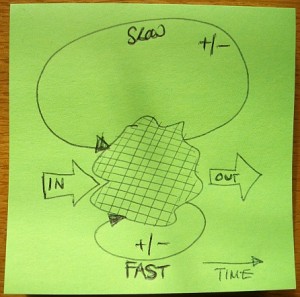

In effect, the Executive organ becomes progressively cut off from objective reality – and this lack of accurate information impairs the Humility Feedback Loop further – accelerating the further enlargement of the egoma.

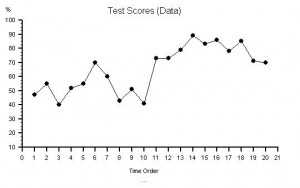

A dangerous positive feedback loop is now created that leads to a self-amplifying spiral of distorted perception and a progressive decline of judgement and effective decision making.

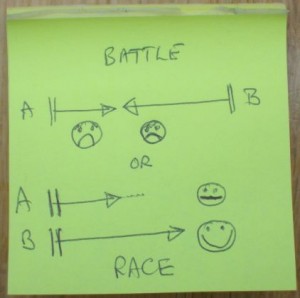

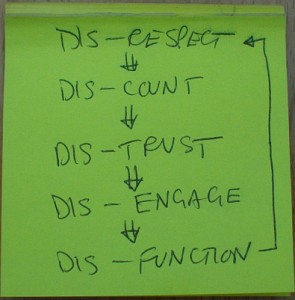

The external manifestation of this state is a characteristic behaviour called “dystrustosis” – or difficulty in extending trust to others combined with a progressive loss of self-trust.

The unwitting sufferer becomes progressively deaf, blind, fearful, delusional, paranoid and insecure – often distancing themselves emotionally and physically and communicating only via intermediaries using One-Way-Directives.

Those who attempt to communicate with the sufferer of this insidious condition often resort to SHOUTING and using BIG LETTERS which, unfortunately, only mirrors the same behaviour. As the sufferer’s perception of reality becomes more distorted their lack of insight and humility blocks them from considering themselves as a contributor to the problem.

The ensuing conflict only serves to accelerate their decline and the sufferer progresses to the stage of “fulminant egomatosis”.

“Fulminant egomatosis” is a condition that is easy to identify and to diagnose. Just listen for the shouting, observe the dystrustosis and feel the fear.

“Fulminant egomatosis” is a condition that is easy to identify and to diagnose. Just listen for the shouting, observe the dystrustosis and feel the fear.

Unfortunately, it is a difficult condition to manage because of the lack of awareness and insight that are the cardinal signs.

Many affected leaders and their organisations now enter a state of Denial – unconsciously hoping that the problem will resolve itself – which is indeed what happens eventually – though not in the way they desperately hope for.

In the interim, the health of the organisation deteriorates and many executives succumb, unaware of, or unwilling to acknowledge the illness that claimed them; meekly accepting the “inevitable fate” and submitting to the terminal option – usually delivered by the Chair of the Board – Retire or Resign!

The circling corporate vultures squabble over the fiscal remains – leaving no tangible sign to mark the passing of the sufferer and their hapless organisation. There are no graveyards for the victims of fulminant egomatosis and the memory of their passing soon fades from the collective memory. Failure is a taboo subject – an undiscussable.

Some organisations become aware of their affliction while they are still alive, but only after they have reached the terminal stage and are too sick to save. The death throes are destructive and unpleasant to watch – and unfortunately fuel the self-justifying delusion of other infected organisations who erroneously conclude that “it could never happen to them” and then unwittingly follow the same path.

Some organisations become aware of their affliction while they are still alive, but only after they have reached the terminal stage and are too sick to save. The death throes are destructive and unpleasant to watch – and unfortunately fuel the self-justifying delusion of other infected organisations who erroneously conclude that “it could never happen to them” and then unwittingly follow the same path.

Unfortunately, egomatosis is an infectious cultural disease. The spores, or “memes” as they are called, can spread to other organisations. Just as Dr Ignaz Semmelweis discovered in 1847, the agents-of-destruction are often carried on the hands of those who perform organisational postmortems. These meme vectors are often the very people brought into assist the ailing organisation, and so become chronically infected themselves and gravitate to others who share their delusions. They are excluded by healthy organisations, but their siren-calls sound plausible and they gain entry to weaker organisations who are unaware that they carry the dangerous memes! Actively employing the services of management consultants in preference to encouraging organisational innovation incurs a high risk of silent infection! Appearance of the symptoms and signs is often delayed and by then it may be too late.

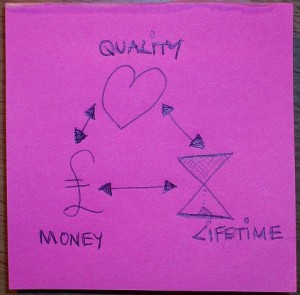

The organisations that are naturally immune to egomatosis were “built to last” because they were born with a well-developed sense of purpose, vision, humility, confidence and humour. They habitually and unconsciously look for, detect, and defuse the early signs of egomatosis. They do not fear failure, and they have learned to leverage the gap between intent and impact. These organisations have a strong cultural immune system and are able to both prevent infection and disarm the toxic-memes they inevitably encounter. They are safe, fun, challenging, exciting, innovative and motivating, places to work – characteristics that serve to strengthen their immunity, boost their resilience, and secure their future.

Some infected organisations are fortunate enough to become aware of their infection before it is too late, and they are able to escape the vicious cycle of decline. These “good to great” organisations have enough natural humility to learn by observing the fate of others and are able to detect the early symptoms and to seek help from someone who understands their illness and can guide their diagnosis and treatment. Such healers facilitate and demonstrate rather than direct and delegate.

All organisations are susceptible to egomatosis, so prevention is preferable to cure.

To prevent the disease, organisations must consciously and actively develop their internal and external feedback loops – using all their senses – including their olfactory organ. Cultural and political bull**** has a characteristic odour!

They also regularly exercise their Humility Feedback Loop to keep it healthy – and they have discovered that the easiest way to do that is to challenge themselves – to actively look for their own gaps and gaffes – to look for their own positive deviants – to search out opportunities to improve – and to practice the very things that they know they are not good at.

They are prepared to be proved lacking and have learned to stop, look, laugh at themselves – then listen, learn, act, improve and share.

There is no known cure for egomatosis – it is a consequence of the 1.3 kg of ChimpWare between our ears that we have inherited from our ancestors – so vigilance must be maintained throughout the life of the organisation.