Knowledge is not the same as Understanding.

Knowledge is not the same as Understanding.

We all know that the sun rises in the East and sets in the West; most of us know that the oceans have a twice-a-day tidal cycle and some of us know that these tides also have a monthly cycle that is associated with the phase of the moon. We know all of this just from taking notice; remembering what we see; and being able to recognise the patterns. We use this knowledge to make reliable predictions of the future times and heights of the tides; and we can do all of this without any understanding of how tides are caused.

Our lack of understanding means that we can only describe what has happened. We cannot explain how it happened. We cannot extract meaning – the why it happened.

People have observed and described the movements of the sun, sea, moon, and stars for millennia and a few could even predict them with surprising accuracy – but it was not until the 17th century that we began to understand what caused the tides. Isaac Newton developed enough of an understanding to explain how it worked and he did it using a new concept called gravity and a new tool called calculus. He then used this understanding to explain a lot of other unexplained things and suddenly the Universe started to make a lot more sense to everyone. Nowadays we teach this knowledge at school and we take it for granted. We assume it is obvious and it is not. We are no smarter now that people in the 17th Century – we just have a deeper understanding (of physics).

Understanding enables things that have not been observed or described to be predicted and explained. Understanding is necessary if we want to make rational and reliable decisions that will lead to changes for the better in a changing world.

So, how can we test if we only know what to do or if we actually understand what to do?

If we understand then we can demonstrate the application of our knowledge by solving old and new problems effectively and we can explain how we do it. If we do not understand then we may still be able to apply our knowledge to old problems but we do not solve new problems effectively or efficiently and we are not able to explain why.

But we do not want the risk of making a mistake in order to test if we have and understanding-gap so how can we find out? What we look for is the tell-tale sign of an excess of knowledge and a dearth of understanding – and it has a name – it is called “bureaucracy”.

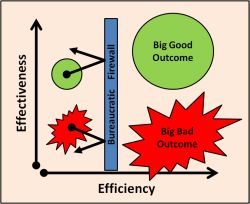

Suppose we have a system where the decisions-makers do not make effective decisions when faced with new challenges – which means that their decisions lead to unintended adverse outcomes. It does not take very long for the system to know that the decision process is ineffective – so to protect itself the system reacts by creating bureaucracy – a sort of organisational damage-limitation circle of sand-bags that limit the negative consequences of the poor decisions. A bureaucratic firewall so to speak.

Unfortunately, while bureaucracy is effective it is non-specific, it uses up resources and it slows everything down. Bureaucracy is inefficiency. What we get as a result is a system that costs more and appears to do less and that is resistant to any change – not just poor decisions – it slows down good ones too.

The bureaucratic barrier is important though; doing less bad stuff is actually a reasonable survival strategy – until the cost of the bureaucracy threatens the systems viability. Then it becomes a liability.

So what happens when a last-saloon-in-town “efficiency” drive is started in desperation and the “bureaucratic red tape” is slashed? The poor decisions that the red tape was ensnaring are free to spread virally and when implemented they create a big-bang unintended adverse consequence! The safety and quality performance of the system drops sharply and that triggers the reflex “we-told-you-so” and rapid re-introduction of the red-tape, plus some extra to prevent it happening again. The system learns from its experience and concludes that “higher quality always costs more” and “don’t trust our decision-makers” and “the only way to avoid a bad decision is not to make/or/implement any decisions” and to “the safest way to maintain quality is to add extra checks and increased the price”. The system then remembers this new knowledge for future reference; the bureaucratic concrete sets hard; and the whole cycle repeats itself. Ad infinitum.

So, with this clearer insight into the value of bureaucracy and its root cause we can now design an alternative system: to develop knowledge into understanding and by that route to improve our capability to make better decisions that lead to predictable, reliable, demonstrable and explainable benefits for everyone. When we do that the non-specific bureaucracy is seen to impede progress so it makes sense to dismantle the bits that block improvement – and keep the bits that block poor decisions and that maintain performance. We now get improved quality and lower costs at the same time, quickly, predictably and without taking big risks, and we can reinvest what we have saved in making making further improvements and developing more knowledge, a deeper understanding and wiser decisions. Ad infinitum.

The primary focus of Improvement Science is to expand understanding – our ability to decide what to do, and what not to; where and where not to; and when and when not to – and to be able to explain and to demonstrate the “how” and to some extent the “why”.

One proven method is to See, then to Do, and then to Teach. And when we try that we discover to our surprise that the person whose understanding increases the most is the teacher! Which is good because the deeper the teachers understanding the more flaxible, adaptable and open to new learning they become. Education and bureaucracy are poor partners.