“There are known knowns; there are things we know we know.

We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know.

But there are also unknown unknowns – the ones we don’t know we don’t know.” Donald Rumsfeld 2002.

This infamous quotation is a humorously clumsy way of expressing a profound concept. This statement is about our collective ignorance – and it hides a beguiling assumption which is that we are all so similar that we just have to accept the things that we all do not know. It is OK to be collectively and blissfully ignorant. But is this OK? Is this not the self-justifying mantra of those who live in the Land of the Blind?

Our collective blissful ignorance holds the promise of great unknown gains; and harbours the potential of great untold pain.

Our collective knowledge is vast and is growing because we have dissolved many Unknowns. For each there must have been a point in time when the first person become painfully aware of their ignorance and, by some means, discovered some new knowledge. When that happened they had a number of options – to keep it to themselves, to share it with those they knew, or to share it with strangers. The innovators dilemma is that when they share new knowledge they know they will cause emotional pain; because to share knowledge with the blissfully ignorant implies pushing them to the state of painful awareness.

We are social animals and we demonstrate empathy and respect for others, so we do not want to deliberately cause them emotional pain – even the short term pain of awareness that must preceed the long term gain of knowledge, understanding and wisdom. It is the constant challenge that every parent, every teacher, every coach, every mentor, every leader and every healer has to learn to master.

So, how do we deal with the situation when we are painfully aware that others are in the state of blissful ignorance – of not knowing what they do not know – and we know that making them aware will be emotionally painful for them – just as it was for us? We know from experience that that an insensitive, clumsy, blunt, brutal, just-tell-it-as-it is approach can cause pain-but-no-gain; we have all had experience of others who seem to gain a perverse pleasure from the emotional impact they generate by triggering painful awareness. The disrespectful “means-justifies-the-ends” and “cruel-to-be-kind” mindset is the mantra of those who do not walk their own talk – those who do not challenge their own blissful ignorance – those who do not seek to gain an understanding of how to foster effective learning without inflicting emotional pain.

The no-pain-no-gain life limiting belief is an excuse – not a barrier. It is possible to learn without pain – we have all been doing it for our whole lives; each of us can think of people who inspired us to learn and to have fun doing so – rare and memorable role models, bright stars in the darkness of disappointment. Our challenge is to learn how to inspire ourselves.

The first step is to create an emotionally Safe Environment for Learning and Fun (SELF). For the leader/teacher/healer this requires developing an ability to build a culture of trust by actively unlearning their own trust-corroding-behaviours.

The second step is to know what we know – to be sure of our facts and confident that we can explain and support what we know with evidence and insight. To deliberately push someone into painful awareness with no means to guide them out of that dark place is disrespectful and untrustworthy behaviour. Learning how to teach what we know is the most effective means to discover our own depth of understanding and it is an energising exercise in humility development!

The third step is for us to have the courage to raise awareness in a sensitive and respectful way – sometimes this is done by demonstrating the knowledge; sometimes this is done by asking carefully framed questions; and sometimes it is done as a respectful challenge. The three approaches are not mutually exclusive: leading-by-example is effective but leaders need to be teachers and healers too.

At all stages the challenge for the leader/teacher/healer is to to ensure they maintain an OK-OK mental model of those they influence. This is the most difficult skill to attain and is the most important. The “Leadership and Self-Deception” book that is in the Library of Improvement Science is a parable that decribes this challenge.

So, how do we dissolve the One-Eyed Man in the Land of the Blind problem? How do we raise awareness of a collective blissful ignorance? How do we share something that is going to cause untold pain and misery in the future – a storm that is building over the horizon of awareness.

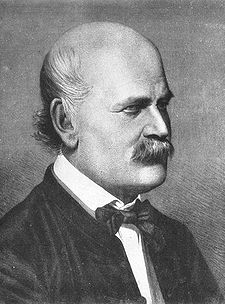

Ignaz Semmelweis (1818-1865) was the young Hungarian doctor who in 1847 discovered the dramatic live-saving benefit of the doctors cleaning their hands before entering the obstetric ward of the Vienna Hospital. This was before “germs” had been discovered and Semmelweis could not explain how his discovery worked – all he could do was to exhort others to do as he did. He did not learn how the method worked, he did not publish his data, and he demonstrated trust-eroding behaviour when he accused others of “murder” when they did not do as he told them. The fact the he was correct did not justify the means by which he challenged their collective blissful ignorance (see http://www.valuesystemdesign.com for a fuller account). The book that he eventually published in 1861 includes the data that supports our modern understanding of the importance of hand hygiene – but it also includes a passionate diatribe of how he had been wronged by others – a dramatic example of the “I’m OK and The Rest of the World is Not OK” worldview. Semmelweis was committed to a lunatic asylum and died there in 1865.

Ignaz Semmelweis (1818-1865) was the young Hungarian doctor who in 1847 discovered the dramatic live-saving benefit of the doctors cleaning their hands before entering the obstetric ward of the Vienna Hospital. This was before “germs” had been discovered and Semmelweis could not explain how his discovery worked – all he could do was to exhort others to do as he did. He did not learn how the method worked, he did not publish his data, and he demonstrated trust-eroding behaviour when he accused others of “murder” when they did not do as he told them. The fact the he was correct did not justify the means by which he challenged their collective blissful ignorance (see http://www.valuesystemdesign.com for a fuller account). The book that he eventually published in 1861 includes the data that supports our modern understanding of the importance of hand hygiene – but it also includes a passionate diatribe of how he had been wronged by others – a dramatic example of the “I’m OK and The Rest of the World is Not OK” worldview. Semmelweis was committed to a lunatic asylum and died there in 1865.

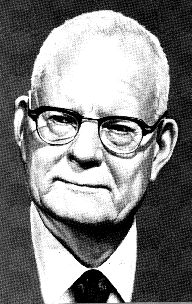

W Edwards Deming (1900-1993) was the American engineer, mathematician, mathematical physicist, statistician and student of Walter A. Shewhart who learned the importance of quality in design. After WWII he was part of the team who helped to rebuild the Japanese economy and he taught the Japanese what he had learned and practiced during WWII – which was how to create a high-quality, high-speed, high-efficiency process which, ironically, was building ships for the war effort. Later Deming attempted, and failed, to influence the post-war generation of managers that were being churned out by the new business schools to serve the growing global demand for American mass produced consumer goods. Deming returned to relative obscurity in the USA until 1980 when his teachings were rediscovered when Japan started to challenge the USA economically by producing higher-quality-and-lower-cost consumer products such as cars and electronics ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/W._Edwards_Deming). Before he died in 1993 Deming wrote two books – Out of The Crisis and The New Economics in which he outlines his learning and his philosophy and in which he unreservedly and passionately blames the managers and the business schools that trained them for their arrogant attitude and disrespectful behaviour. Like Semmelweis, the fact that his books contain a deep well of wisdom does not justify the means by which he disseminated his criticism of poeple – in particular of senior management. By doing so he probably created resistance and delayed the spread of knowledge.

W Edwards Deming (1900-1993) was the American engineer, mathematician, mathematical physicist, statistician and student of Walter A. Shewhart who learned the importance of quality in design. After WWII he was part of the team who helped to rebuild the Japanese economy and he taught the Japanese what he had learned and practiced during WWII – which was how to create a high-quality, high-speed, high-efficiency process which, ironically, was building ships for the war effort. Later Deming attempted, and failed, to influence the post-war generation of managers that were being churned out by the new business schools to serve the growing global demand for American mass produced consumer goods. Deming returned to relative obscurity in the USA until 1980 when his teachings were rediscovered when Japan started to challenge the USA economically by producing higher-quality-and-lower-cost consumer products such as cars and electronics ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/W._Edwards_Deming). Before he died in 1993 Deming wrote two books – Out of The Crisis and The New Economics in which he outlines his learning and his philosophy and in which he unreservedly and passionately blames the managers and the business schools that trained them for their arrogant attitude and disrespectful behaviour. Like Semmelweis, the fact that his books contain a deep well of wisdom does not justify the means by which he disseminated his criticism of poeple – in particular of senior management. By doing so he probably created resistance and delayed the spread of knowledge.

History is repeating itself: the same story is being played out in the global healthcare system. Neither senior doctors nor senior managers are aware of the opportunity that the learning of Semmelweis and Deming represent – the opportunity of Improvement Science and of the theory, techniques and tools of Operations Management. The global healthcare system is in a state of collective blissful ignorance. Our descendents be the recipients of of decisions and the judges of our behaviour – and time is running out – we do not have the luxury of learning by making the same mistake.

Fortunately, there is an growing group of people who are painfully aware of the problem and are voicing their concerns – such as the Institute of Healthcare Improvement in America. There is a smaller and less well organised network of people who have acquired and applied some of the knowledge and are able to demonstrate how it works – the Know Hows. There appears to be an even smaller group who understand and use the principles but do it intuitively and unconsciously – they dem0nstrate what is possible but find it difficult to teach others how to do what they do. It is the Know How group that is the key to dissolving the problem.

The first collective challenge is to sign-post some safe paths from Collective Blissful Ignorance to Individual Know How. The second collective challenge is to learn an effective and respectful way to raise awareness of the problem – a way to outline the current reality and the future opportunity – and a way that illuminates the paths that link the two.

In the land of the blind the one-eyed man is the person who discovers that everyone is wearing a head-torch by accidentally finding his own and switching it on!