Have you ever had the experience of trying to help someone with a problem, not succeeding, and being left with a sense of irritation, disappointment, frustration and even anger?

Have you ever had the experience of trying to help someone with a problem, not succeeding, and being left with a sense of irritation, disappointment, frustration and even anger?

Was the dialog that led up to this unhappy outcome something along the lines of:

A: I have a problem with …

B: What about trying …

A: Yes, but ….

B: What about trying ….

A: Yes, but …

… and so on until you run out of ideas, patience or both.

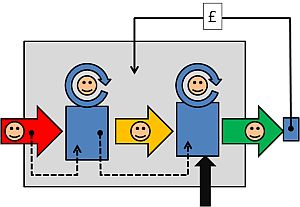

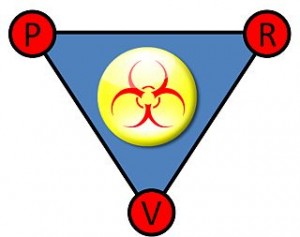

If this sounds familiar then it is likely that you have been unwittingly sucked into a Drama Triangle – an unconscious, habitual pattern of behaviour that we all use to some degree.

This endemic behaviour has a hidden purpose: to feed our belonging need for social interaction.

The theory goes something like this – we are social animals and we need social interaction just as much as we need oxygen, water and food. Without it we become psychologically malnourished and this insight explains why prolonged solitary confinement is such an effective punishment – it is the psychological equivalent to starvation.

The emotional sustenance we want most is unconditional love (UCL) – the sort we usually get from our parents, family and close friends. Repeated affirmation that we are ‘OK’ with no strings attached.

The downside of our unconscious desire for UCL is that it offers a way for others to control our behaviour and those who choose to abuse that power are termed ‘manipulative’. This control is done by adding conditions: “I will give you the affirmation you crave IF you do what I want“. This is conditional love (CL).

When we are born we are completely powerless, and completely dependent on our parents – in particular our mother. As we get older and start to exert our free will we learn that our society has rules – we cannot just follow every selfish desire.

Our parents unconsciously employ CL as a form of behavioural control and it is surprisingly effective: “If you are a good boy/girl then …“. So, as children, we learn the technique from our parents.

This in itself is not a problem; but it can become a problem when CL is the only sort available and when the intention is to further only the interests of the giver. When this happens it becomes … manipulation.

The apparently harmless playground threat of “If you don’t do what I want then I won’t be your friend anymore” is the practice script of a future manipulator – and it feeds on a limiting-belief in the unconscious mind of the child – the belief that there is a limited supply of UCL and that someone else controls it.

And because we make this assumption at the pre-verbal stage of child development, it becomes unconscious, habitual, unspoken and second nature.

Our invalid childhood belief has a knock-on effect; we learn to survive on CL because “No Love” is the worst of all options; it is the psychological equivalent of starvation.

And we learn to put up with second best, and because CL offers inferior emotional nourishment we need a way of generating as much as we want, on-demand.

So we employ the behaviour we were unwittingly taught by our patents – and the Drama Triangle becomes our on-demand-generator-of-second-rate-emotional-sustenance.

The tangible evidence of this “programming” is an observable behaviour that is called “game playing” and was first described by Eric Berne in the famous book “Games People Play“.

Berne described many different Games and they all have a common pattern and a common objective – to generate second-rate emotional food (or ‘transactions’ to use Berne’s language). But our harvest comes at a price – the transactions are unhealthy – not enough to harm us immediately – but enough to leave us feeling dissatisfied and unhappy.

But what choice do we believe we have?

If we were given the options of breathing stale air or suffocating what would we do?

If we assume our options are to die of thirst or drink stagnant pond-water what would we do?

If we believe our only options are to starve or eat rubbish what would we do?

Our survival instinct is much stronger than our belonging need, so we choose unhealthy over deadly and eventually we become so habituated to game-playing that we do not notice it any more.

Excessive and prolonged exposure to the Drama Triangle is the psychological equivalent of alcoholic liver cirrhosis. Permanent and irreversible psychological scarring called cynicism.

It is important to remember that this is learned behaviour – and therefore it can be unlearned – or rather overwritten with a healthier habit.

Just by becoming aware of the problem, and understanding the root cause of the Drama Triangle, an alternative pathway appears.

We can challenge our untested assumption that UCL is limited and that someone else controls the supply. We can consider the alternative hypothesis: that the supply of UCL is unlimited and that we control the supply.

Q: How easy is it for us to offer someone else UCL?

Easy – we see it all the time. How do you feel when someone gives a genuine “Thank You”, cheers you on, celebrates your success, seeks your opinion, and recommends you to others – with no strings attached. These are all forms of UCL that anyone can practice; by making a conscious choice to give with no expectation of a return.

For many people it feels uncomfortable at first because the game-playing behaviour is so deeply ingrained – and game-playing is particularly prevalent in the corridors of power where it is called “politics”.

Game-free behaviour gets easier with practice because UCL benefits both the giver and the receiver – it feels healthier – there is no need for a payback, there is no score to be kept, no emotional account to balance. It feels like a breath of fresh air.

So, next time you feel that brief flash of irritation at the start of a conversation or are left with a negative feeling after a conversation just stop and ask yourself “Was I just sucked into a Drama Triangle?”

Anyone who is able to “press your button” is hooking you into a game, and it takes two to play.

Now consider the question “And to what extent was I unconsciously colluding?“

The tactic to avoid the Drama Triangle is to learn to sense the emotional “hook” that signals the invitation to play the Game; and to consciously deflect it before it embeds into your unconscious mind and triggers an unconscious, habitual, reflex, emotional reaction.

One of the most potent barriers to change is when we unconsciously compute that our previously reliable sources of CL are threatened by the change. We have no choice but to oppose the change – and that choice is made unconsciously. So, we unwittingly undermine the plan.

The symptoms of this unconscious behaviour are obvious when you know what to look for … and the commonest reaction is:

“Yes … but …”

and the more intelligent and invested the person the more cogent and rational the argument will sound.

The most effective response is to provide evidence that disproves the defensive assertion – not the person’s opinion – and before taking on this challenge we need to prepare the evidence.

By demonstrating that their game-playing behaviour no longer leads to the expected payoff, and at the same time demonstrating that game-free behaviour is both possible and better – we demonstrate that the underlying, unconscious, limiting belief is invalid.

And by that route we develop our capability for game-free social interactions.

Simple enough in theory, and it does works in practice, though it can be difficult to learn because game-playing is such an ingrained behaviour. It does get easier with practice and the ultimate reward is worth the investment – a healthier emotional environment. And that is transformational.

There is always more than one way to look at something and each perspective is complementary to the others.

There is always more than one way to look at something and each perspective is complementary to the others.