One of the most surprising aspects of systems is how some big changes have no observable effect and how some small changes are game-changers. Why is that?

The technical name for this phenomenon is leverage points.

When a nudge is made at a leverage point in a real system the impact is amplified – so a small cause can have a big effect.

When a nudge is made at a leverage point in a real system the impact is amplified – so a small cause can have a big effect.

And when a big kick is made where there is no leverage point the effort is dissipated. Like flogging a dead horse.

Other names for leverage points are triggers, buttons, catalysts, fuses etc.

The fact that there is a big effect does not imply it is a good effect.

Poking a leverage point can trigger a catastrophe just as it can trigger a celebration. It depends on how it is poked.

Perhaps that is one reason people stay away from them.

But when our heath care system performance is in decline, if we do nothing or if we act but stay away from leverage points (i.e. flog the dead horse) then we will deny ourselves the opportunity of improvement.

So, we need a way to (a) identify the leverage points and (b) know how to poke them positively and know how to not poke them into delivering a catastrophe.

Here is a couple of real examples.

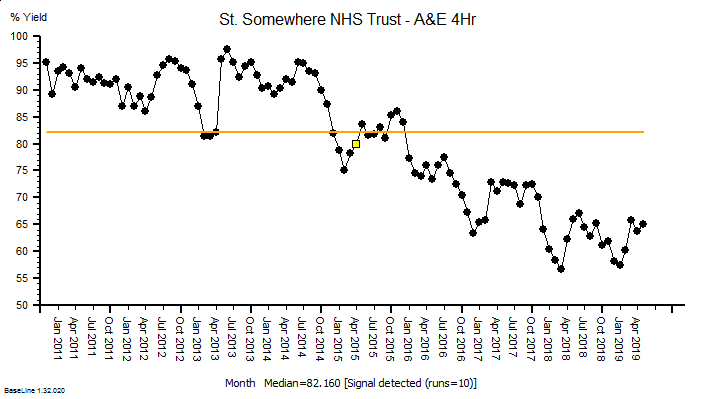

The time-series chart above shows the A&E performance of a real acute trust. Notice the pattern as we read left-to-right; baseline performance is OKish and dips in the winters, and the winter dips get deeper but the baseline performance recovers. In April 2015 (yellow flag) the system behaviour changes, and it goes into a steady decline with added winter dips. This is the characteristic pattern of poking a leverage point in the wrong way … and the fact it happened at the start of the financial year suggests that Finance was involved. Possibly triggered by a cost-improvement programme (CIP) action somewhere else in the system. Save a bit of money here and create a bigger problem over there. That is how systems work. Not my budget so not my problem.

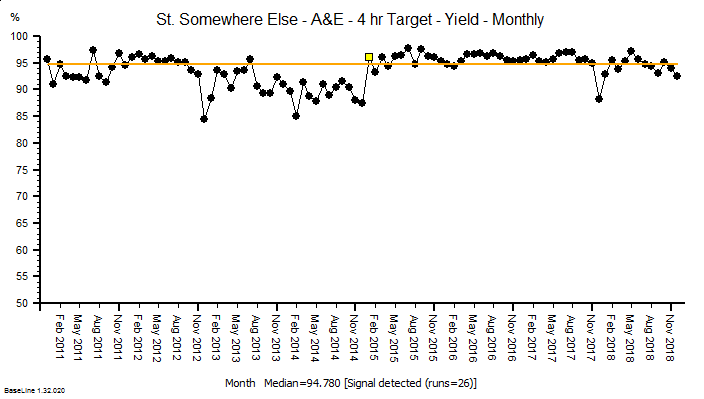

Here is a different example, again from a real hospital and around the same time. It starts with a similar pattern of deteriorating performance and there is a clear change in system behaviour in Jan 2015. But in this case the performance improves and stays improved. Again, the visible sign of a leverage point being poked but this time in a good way.

In this case I do know what happened. A contributory cause of the deteriorating performance was correctly diagnosed, the leverage point was identified, a change was designed and piloted, and then implemented and validated. And it worked as predicted. It was not a fluke. It was engineered.

So what is the reason that the first example much more commonly seen than the second?

That is a very good question … and to answer it we need to explore the decision making process that leads up to these actions because I refuse to believe that anyone intentionally makes decisions that lead to actions that lead to deterioration in health care performance.

And perhaps we can all learn how to poke leverage points in a positive way?