Learning how to manage is as vital as learning how to lead.

by Julian Simcox

Recently I blogged to introduce the re-publication of my 10 year old essay:

“Intervening into Personal and Organisational Systems by Powerfully Leading and Wisely Managing”

The key ideas in that essay were seven fold:

- Aiming to develop Leadership separately from Management is likely to confuse anyone targeted by a separatist training programme, the reality being that everyone in organisational life is necessarily and simultaneously both Managing and Leading (M/L) and often desperately trying to integrate them as two very different action-logics.

- Managing and Leading are not roles but ways of thinking and acting that need to be intently chosen, according to the particular learning context (one of three) that any Managerial Leader (12) is facing.

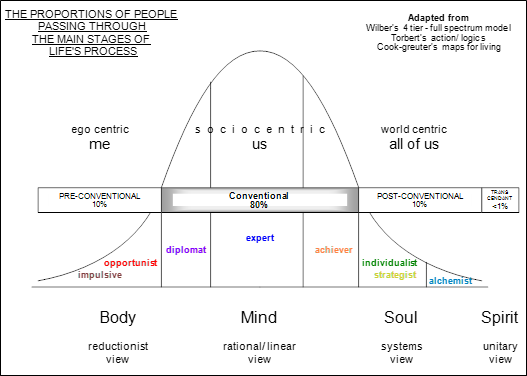

- Like in Stephen Covey’s “Maturity Continuum” (8) M/L capability evolves over time (see the diagram below) and makes possible a transformational outcome, if supported in one’s organisation by sufficient and timely post-conventional thinking.

- Such an outcome (9,10,11,14,17,19,20,21,23) occurred in Toyota from 1950, making it possible for the organisation to evolve into what Peter Senge (18) calls a “Learning Organisation” – one in which improvement science (4) ensues continually from the bottom-up, within a structure that has evolved top-down.

- In Toyota’s case it was W. Edwards Deming who is most credited with having been the catalyst. Jim Collins (6) evidences eleven other examples of an organisational transformation sparked by an individual with a post-conventional world view that transcended a pre-existing conventional one.

- Deming talked a lot about ways of thinking – paradigms – that, like Euclidian geometry, make sense in their own world, but not outside it. When speaking with anyone in a client organisation he always aimed at being empathic to a person’s individual frame of reference. He was interested in how individuals make their own common sense because he had learned that it is this that often negatively impacts an individual’s decision-making process and hence their impact on an organisational system that needs to continually learn – a phenomenon he called “tampering”.

- The diagram seeks to capture the ways in which paradigms (world views) collectively and sequentially evolve. It combines the research of several practitioners (2,7,15,16) who sought to empirically trace the archetypal evolution of individual sense-making.

In 2013, Don Berwick (5) recommended to the UK government that, in order to prioritise quality and safety, the National Health Service must become a Deming-style learning organisation. The NHS however is not one single organisation, it is a thousand organisations – both privately and publically owned. Yet if structured with “Liberating Disciplines” (22) via appropriately set central standards (e.g. tools that prompt thinking that is scientifically methodical), each can be invited as a single organisation to transform themselves into a body with learning its core value. Berwick seems to appreciate that out of the apparently sufficient conventional thinking, enough post-conventional managerial leadership will then have a chance to take root, and in time bloom.

The purpose of this blog is to introduce a second essay:

“Managerial Leadership: Five action-logics viewed via two developmental lenses.”

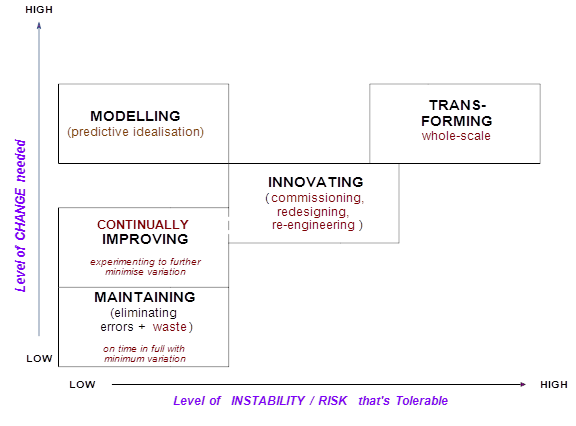

In the first essay I used P-D-S-A as the integrative link between Managing and Leading – offering a total of just three learning contexts, but this always felt a little over-simplistic and in 2005 when coaching my daughter Josie – then in her sandwich year as an undergraduate trainee in the hospitality industry – I was persuaded by her to further sub-divide the two M/L modes – replacing two with four:

- maintaining

- continually improving

- innovating

- transforming.

Applying this new 4 action-logic model, Josie succeeded in transforming the fortunes of her hotel – winning a national award for her efforts – and this made me wonder if she might be on to something important?

I decided to use the new version of the model to explore what it would look like through first a “conventional” lens, and then second a “post-conventional” lens – illustrating the kinds of paradigm shifts that one might see in action when inside a learning organisation, in particular the way that accountabilities for performance are handled.

It is hard to describe a post-conventional way of seeing things to someone who developmentally has discovered only the conventional way – about 85% of adults. It is as if the instructions about how to get out of the box are on the outside. It is hoped that this essay may help some individuals unlock this conundrum. In a learning organisation for example it turns out that real-time data and feedback are essential for continually prompting individuals and organisations to rapidly evolve a new way of seeing.

BaseLine® for example is a tool that has been designed with this in mind. It allows conventional organisations and individuals, even those considering themselves relatively innumerate, to develop post-conventional habits; simply by using the time-series data that in many cases is already being collected – albeit usually for reasons of top-down accountability rather than methodical improvement. In this way, healthy developmental conversation gets sparked – and at all organisational levels: bottom, middle and top.

It also turns out that Continuous Improvement when seen though the second lens is not the same as Continual Improvement (mode 2) – and this is another one of the paradigm shifts that in the essay gets explained. Here is the model as it then appears:

Note that a fifth action-logic mode, modelling, is also now included. This emerged out of conversations I was having with Simon Dodds when writing the final draft in 2011. The essence of this mode is embodied in a phrase coined by the late Russell Ackoff – “idealized design” (1) – using modern computing technology to facilitate transformative change within tolerable levels of risk.

People often readily admit to spending much of their life in mode 1 (maintaining), whilst really preferring to be in mode 3 (innovating) – even admitting to seeing mode 1 as relatively boring, or at best as overly bureaucratic. Such individuals are especially prone to tampering, and may even shun regimes in which they feel overly controlled. What the post-conventional worldview offers however is not the prospect of being controlled, but the prospect of being in control – whilst simultaneously letting go – a paradox that is not easy to get unless developmentally ready – hence the 2005 essay. This goes for the tools too – especially when being deployed with the full cultural support that can flow from an organisation imbued with sufficient post-conventional design.

If the organisation can be designed to sufficiently support the right people to take control of each critical process or sub-system, who at the right level (usually the lowest point in the hierarchy that accountability may be accepted), may feel safely equipped to make sound decisions, genuine empowerment then becomes possible. Essentially, people then feel safe enough to self-empower and take charge of their system.

Toyota are an exemplar “learning organisation” – actually a system of organisations that work so harmoniously as a whole that by continually adapting to its changing environment, risk can be smoothly managed. Their preoccupation from bottom to top is understanding in real time what is changing so that changes (to the system) can then be proactively and wisely made. Each employee at each organisational level is educated to both manage and lead.

This approach has enabled them to grow to become the largest volume car maker in the world – and largely via organic growth alone. They have achieved this simply by constantly delivering what the customer wants with low variation (hence high reliability) and by continually studying that variation to uncover the real causes of problems. Performance is continually assessed over time and seen largely as pertaining to the system rather than being down to any one individual. Job hoppers – who though charismatic may also be practiced at being able to avoid having to live with the longer-term consequences of their actions – are not appointed to key roles.

Some will read the essay and say to themselves that little of this applies to me or my organisation – “we’re not Toyota, we’re not a private company, and we’re not even in manufacturing”. That however is likely to be a conventional view. The post-conventional principles described in the essay apply as much to service industries as to the public sector – both commissioners and providers – some of whom would intentionally evolve a post-conventional culture if given the space to do so.

At the very least I hope to have succeeded in convincing you, even if you don’t buy in to the notion of a Berwick-style learning system, that schooling people in management or leadership separately, or without a workable definition of each, is likely to be both cruel to the individual and to court dysfunction in the organisation.

References

- Ackoff R. Why so few organisations adopt systems thinking – 2007

- Beck D.E & Cowan C.C. – Spiral Dynamics – Mastering Values, Leadership, and Change – 1996

- Berwick D. – The Science of Improvement – 2008 : http://www.allhealth.org/BriefingMaterials/JAMA-Berwick-1151.pdf

- Berwick D. – The Science of Improvement – 2008 : http://www.allhealth.org/BriefingMaterials/JAMA-Berwick-1151.pdf

- Berwick Donald M. – Berwick Review into patient safety – 2013

- Collins J.C. – Level 5 Leadership: The triumph of Humility and Fierce Resolve – HBR Jan 2001

- Cook-Greuter. S. – Maps for living: ego-Development Stages Symbiosis to Conscious Universal Embeddedness – 1990

- Covey. S.R. – The 7 habits of Highly Effective People – 1989 (ISBN 0613191455)

- Delavigne K.T & Robertson J. D. – Deming’s profound changes – 1994

- Deming W. Edwards – Out of the Crisis – 1986 (ISBN 0-911379-01-0)

- Deming W.Edwards – The New Economics – 1993 (ISBN 0-911379-07-X) First edition

- Jaques. E. – Requisite Organisation: A Total System for Effective Managerial Organisation and Managerial Leadership for the 21st Century 1998 (ISBN 1886436045)

- Kotter. J. P. – A Force for Change: How Leadership Differs from Management – 1990

- Liker J.K & Meier D. – The Toyota Way Fieldbook – 2006

- Rooke D and Torbert W.R. – Organisational Transformation as a function of CEO’s Development Stage 1998 (Organisation Development Journal, Vol. 6.1)

- Rooke D and Torbert W.R. – Seven Transformations of Leadership – Harvard Business Review April 2005

- Scholtes Peter R. The Leader’s Handbook: Making Things Happen, Getting Things Done – 1998

- Senge. P. M. – The Fifth Discipline 1990 ISBN 10 – 0385260946

- Spear. S and Bowen H. K- Decoding the DNA of the Toyota Production System – Harvard Business Review Sept/Oct 1999

- Spear. S. – Learning to Lead at Toyota – Harvard Business Review – May 2004

- Takeuchi H, Osono E, Shimizu N. The contradictions that drive Toyota’s success. Harvard Business Review: June 2008

- Torbert W.R. & Associates – Action Inquiry – The secret of timely and transforming leadership – 2004

- Wheeler Donald J. – Advanced Topics in Statistical Process Control – the power of Shewhart Charts – 1995