Improvement implies change, and change implies learningl; so we need to understand how learning works to facilitate change and improvement.

When we learn, we acquire new knowledge, understanding and wisdom. Our ability increases.

Before we can do that we must see the gap between where we are and where we want to be, so that we can focus our attention on filling the gap with the required knowledge, understanding and wisdom. Our awareness must increase before our ability can.

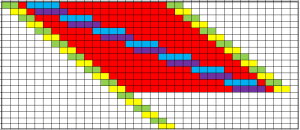

We can sketch a diagram to illustrate the interaction between awareness and ability. The path of learning is shown by the green arrow which starts at the bottom left corner where we are unaware of our inability. Our goal is to master the new knowledge, understanding and wisdom to the point where it becomes second nature. When we can do it without thinking about it.

The first challenge is to see the gap, and to overcome that challenge we need to nurture three traits – willingness, humility and curiosity. We must be willing enough to test our knowledge; we must be humble enough to accept the feedback; and we must be curious enough to ask questions that challenge our assumptions.

Becoming aware of the gap creates an uncomfortable feeling because our awareness increases faster than our ability. But with respect for the ability of others, and with perseverance, discipline and practice we can gradually climb the ability slope to the point where we know how. From that position we can teach how. And over time time our new ability becomes intituive and we become less aware of how we are doing it. That is called “mastery”.

As our ability increases and our awareness decreases (the right hand side of the diagram) we feel a growing sense of confidence and excited anticipation for future learning, change and improvement.

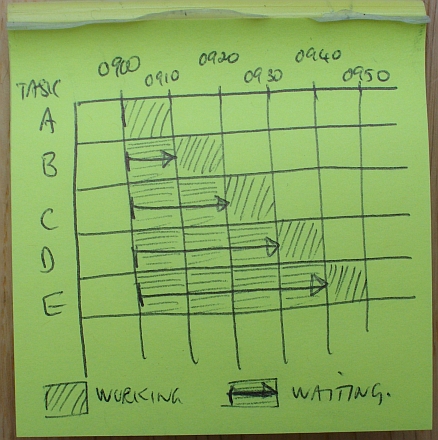

For example, in health care systems it is common to experience what is described as “chronic chaos”. A typical example is a multidisciplinary outpatient clinic that requires the services of a range of specialists to provide specific elements of a patient’s care. The usual experience is a queue of patients waiting (often for hours) and busy staff running around trying to ensure that patients get what they need before the clinic finishes!

The know-how to diagnose and treat the causes of chronic chaos is available, but it is not intuitively obvious (because if it were, we would not have the problematic situation). It starts by making the complex flows within the clinic visible in a way that enables a diagnosis to be established and a plan to be formulated. That visual technique is called a diagnostic Gantt chart and it is over 100 years since it was invented by Henry L Gantt.

One of the most rewarding experiences in health care improvement is to see the surprise and delight on the faces of the staff when they see the behaviour of their clinic as a picture on the wall, and then clearly see a path ahead to a calmer and more productive service.

This is not achieved by someone doing it for them. It is achieved by someone with know-how gently raising a bit of awareness then supporting the clinic team to develop their own ability. This is called the study-plan-do cycle of learning which is the engine of the see-do-teach framework.