Flow improvement-by-design requires being able to see the flows.

We can see movement very easily, but seeing flows is not so easy – particularly when they are mixed-up and unsteady.

One of the most useful tools for visualising flow was invented over 100 years ago by Henry Laurence Gantt (1861-1919).

Henry Gantt was a mechanical engineer from Johns Hopkins University and an early associate of Frederick Taylor. Gantt parted ways with Taylor because he disagreed with the philosophy of Taylorism which was that workers should be instructed what to do by managers (i.e. parent-child transactions according to Eric Berne, inventor of Transactional Analysis). Gantt saw that workers and managers could work together for mutual benefit of themselves and their companies (i.e. adult-adult transactions). At one point Gantt was invited to streamline the production of US munitions for the First World War and his methods were so effective that the Ordinance Department was the most productive department of the armed forces. Gantt favoured democracy over autocracy and is quoted to have said “Our most serious trouble is incompetence in high places. The manager who has not earned his position and who is immune from responsibility will fail time and again, at the cost of the business and the workman“.

Henry Gantt invented a number of different charts – not just the one used in project management which was actually invented 20 years earlier by Karol Adamieki and re-invented by Gantt. It become popularised when it was used in the Hoover Dam project management; but that was after Gantt’s death in 1919.

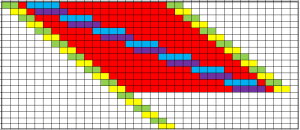

The form of Gantt chart above is called a process template chart and it is designed to show the flow of tasks through a process. Each horizontal line is a task; each vertical column is an interval of time. The colour code in each cell indicates what the task is doing and which resource the task is using during that time interval. Red indicates that the task is waiting. White means that the task is outside the scope of the chart (e.g. not yet arrived or already departed).

The Gantt chart shows two “red wedges”. A red wedge that is getting wider from top to bottom is the pattern created by a flow constraint. A red wedge that is getting narrower from top to bottom is the pattern of a policy constraint. Both are signs of poor scheduling design.

A Gantt chart like this has three primary uses:

1) Diagnosis – understanding how the current flow design is creating the queues and delays.

2) Agnosis – inventing new design options by suspending judgement and lateral thinking.

3) Prognosis – selecting and testing the innovative designs so the ‘fittest for purpose’ can be chosen for implementation.

These three steps are encapsulated in the third “M” of 6M Design® – the Model step.

In this example the design flaw was the scheduling policy. When that was redesigned the outcome was zero-wait performance. No red on the chart at all. The same number of tasks were completed in the same with the same resources used. Just less waiting. Which means less space is needed to store the queue of waiting work (i.e. none in this case).

That this is even possible comes as a big surprise to many people. It feels counter-intuitive. It is however a fact that is easy to demonstrate with a simple table-top game. The lesson we learn from this? Our intuition can trick us.

And the predicted and observed reduction in the size of the queue implies a big cost reduction when the work-in-progress is perishable and needs constant attention [such as patients lying on A&E trolleys and in hospital beds].

So what was the recipe for re-designing this schedule?

A dash of willingness, a splash of humility, a twist of curiosity – plus a few bits of squared paper, some coloured pens, a couple hours, and the assistance of someone who knows how to do it and teach it . The one off cost is peanuts in comparison with the recurring benefit.