When a system reaches the limit of its resilience, it does not fail gradually; it fails catastrophically. Up until the point of collapse the appearance of stability is reassuring … but it is an illusion.

A drowning person kicks frantically until they are exhausted … then they sink very quickly.

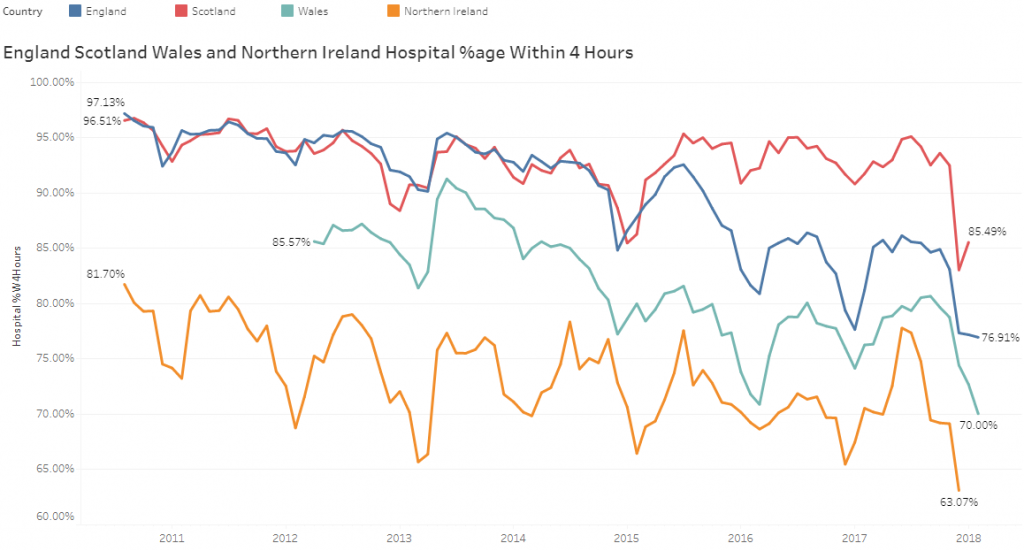

Below is the time series chart that shows the health of the UK Emergency Health Care System from 2011 to the present.

The seasonal cycle is made obvious by the regular winter dips. The progressive decline in England, Wales and NI is also clear, but we can see that Scotland did something different in 2015 and reversed the downward trend and sustained that improvement.

Until, the whole system failed in the winter of 2017/18. Catastrophically.

The NHS is a very complicated system so what hope do we have of understanding what is going on?

The human body is also a complicated system.

In the 19th Century, a profound insight into how the human body works was proposed by the French physiologist, Claude Bernard.

He talked about the stability of the milieu intérieur and his concept came to be called homeostasis: The principle that a self-regulating system can maintain its own stability over a wide range. In other words, it demonstrates resilience to variation.

The essence of a homeostatic system is that the output is maintained using a compensatory feedback loop, one that is assembled by connecting sensors to processors to effectors. Input-Process-Output (IPO).

And to assess how much stress the whole homeostatic system is under, we do not measure the output (because that is maintained steady by the homeostatic feedback design), instead we measure how hard the stabilising feedback loop is working!

And, when the feedback loop reaches the limit of its ability to compensate, the whole system will fail. Quickly. Catastrophically. And when this happens in the human body we call this a “critical illness”.

Doctors know this. Engineers know this. But do those who decide and deliver health care policy know this? The uncomfortable evidence above suggests that they might not.

The homeostatic feedback loop is the “inner voice” of the system. In the NHS it is the collective voices of those at the point of care who sense the pressure and who are paddling increasingly frantically to minimize risk and to maintain patient safety.

And being deaf to that inner voice is a very dangerous flaw in the system design!

Once a complicated system has collapsed, then it is both difficult and expensive to resuscitate and recover, especially if the underpinning system design flaws are not addressed.

And, if we learn how to diagnose and treat these system design errors, then it is possible to “flip” the system back into stable and acceptable performance.

Surprisingly quickly.

So, what is the diagnosis here?

In a word: “push“.

When we push a complicated system of loosely interconnected parts, it does not behave in a predictable way, because it is not rigid – it is resilient. But we want predictable results. We want stability. We want reliability. So, to make our complicated system more predictable and responsive we could make it more rigid … we could add constraints that tie the parts together so they cannot wobble. Rules. Regulations. Bureaucracy. Then we will get predictable performance, yes?

Yes. We do. We get a predictable system collapse (which was not our intention).

But why?

The reason is that we need the resilience because it allows our system to absorb variation. Our system needs to be able to roll with the punches. The more rigid it is the more likely it is to be damaged when it is exposed to variation, which it will inevitably be.

So, what is the treatment here?

In a word: “pull“.

A chain is an example of a system of interlinked, interdependent parts that are not rigidly connected.

A chain is an example of a system of interlinked, interdependent parts that are not rigidly connected.

They are loosely constrained.

If we place a chain on the floor and we try to move it by pushing one end – we get a predictably tangled result. A ineffective and inefficient mess.

If we place chain on the floor and we try to move it by pulling one end – we get a predictable, tidy result. An effective and efficient success.

The NHS Emergency Care System has all the features of a “push” design, otherwise known as a “pressure cooker“, and the chaotic mess is manifest as queues of patients in corridors, frazzled staff desperately trying to keep them safe, plummeting quality, increasing distress, and escalating system cost. There are no winners.

What we all need is a “pull” design in order to restore safety, calm, quality and affordability – and that means we need to learn how to design and build one.

But how?

A chain is a complicated passive system – the links are just bits of metal – and they will only do what the Laws of Physics dictate.

The NHS Emergency Care System is not made of passive parts – many of the parts are people and they are active and adaptive. They meet, share, question, discuss, decide and set the rules that the system is required to abide by – the arbitrary laws of people – the operational policies. The system “software”.

The NHS is a complex adaptive system (CAS) and to change the system behaviour we just need to diagnose and treat some software ‘bugs’.

The capability to create a fit-for-purpose CAS is called Complex Adaptive Systems Engineering (CASE) and when applied in the health care domain is called Health Care Systems Engineering (HCSE).

And for long-term survival in an ever-changing world, that HCSE capability needs to be part of the system itself. Because then the system can become safe, efficient, effective, affordable, stable, resilient, adaptable, and self-healing.

And that is what we all need.