One of the biggest challenges in Improvement Science is diffusion of an improvement outside the circle of control of the innovator.

One of the biggest challenges in Improvement Science is diffusion of an improvement outside the circle of control of the innovator.

It is difficult enough to make a significant improvement in one small area – it is an order of magnitude more difficult to spread the word and to influence others to adopt the new idea!

One strategy is to shame others into change by demonstrating that their attitude and behaviour are blocking the diffusion of innovation.

This strategy does not work. It generates more resistance and amplifies the differences of opinion.

Another approach is to bully others into change by discounting their opinion and just rolling out the “obvious solution” by top-down diktat.

This strategy does not work either. It generates resentment – even if the solution is fit-for-purpose – which it usually is not!

So what does work?

The key to it is to convert some skeptics because a converted skeptic is a powerful force for change.

But doesn’t that fly in the face of established change management theory?

Innovation diffuses from innovators to early-adopters, then to the silent majority, then to the laggards and maybe even dinosaurs … doesn’t it?

Yes – but that style of diffusion is incremental, slow and has a very high failure rate. What is very often required is something more radical, much faster and more reliable. For that it needs both push from the Confident Optimists and pull from some Converted Pessimists. The tipping point does not happen until the silent majority start to come off the fence in droves: and they do that when the noisy optimists and equally noisy pessimists start to agree.

The fence-sitters jump when the tug-o-war stalemate stops and the force for change becomes aligned in the direction of progress.

So how is a skeptic converted?

Simple. By another Converted Skeptic.

Here is a real example.

We are all skeptical about many things that we would actually like to improve.

Personal health for instance. Something like weight. Yawn! Not that Old Chestnut!

We are bombarded with shroud-waver stories that we are facing an epidemic of obesity, rapidly rising rates of diabetes, and all the nasty and life-shortening consequences of that. We are exhorted to eat “five portions of fruit and veg a day” … or else! We are told that we must all exercise our flab away. We are warned of the Evils of Cholesterol and told that overweight children are caused by bad parenting.

The more gullible and fearful are herded en-masse in the direction of the Get-Thin-Quick sharks who then have a veritable feeding frenzy. Their goal is their short-term financial health not the long-term health of their customers.

The more insightful, skeptical and frustrated seek solace in the chocolate Hob Nob jar.

For their part, the healthcare professionals are rewarded for providing ineffective healthcare by being paid-for-activity not for outcome. They dutifully measure the decline and hand out ineffective advice. Their goal is survival too.

The outcome is predictable and seemingly unavoidable.

So when a disruptive innovation comes along that challenges the current dogma and status quo, the healthy skeptics inevitably line up and proclaim that it will not work.

Not that it does not work. They do not know that because they never try it. They are skeptics. Someone else has to prove it to them.

And I am a healthy skeptic about many things.

I am skeptical about diets – the evidence suggests that their proclaimed benefit is difficult to achieve and even more difficult to sustain: and that is the hall-mark of either a poor design or a deliberate, profit-driven, yet legal scam.

So I decided to put an innovative approach to weight loss to the test. It is not a diet – it is a design to achieve and sustain a healthier weight to height ratio. And for it to work it must work for me because I am a diet skeptic.

The start of the story is HERE

I am now a Converted Healthier Skeptic.

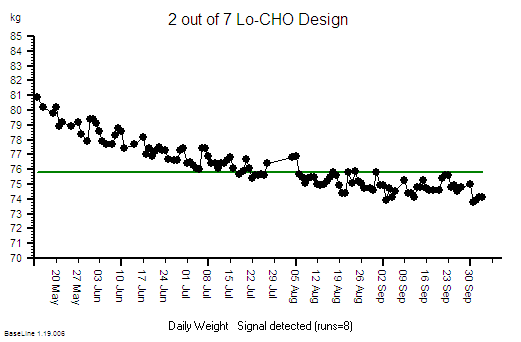

I call the innovative design a “2 out of 7 Lo-CHO” policy and what that means is for two days a week I just cut out as much carbohydrate (CHO) as feasible. Stuff like bread, potatoes, rice, pasta and sugar. The rest of the time I do what I normally do. There is no need for me to exercise and no need for me to fill up on Five Fruit and Veg.

The chart above is the evidence of what happened. It shows a 7 kg reduction in weight over 140 days – and that is impressive given that it has required no extra exercise and no need to give up tasty treats completely and definitely no need to boost the bottom-line of a Get-Thin-Quick shark!

It also shows what to expect. The weight loss starts steeper then tails off as it approaches a new equilibrium weight. This is the classic picture of what happens to a “system” when one of its “operational policies” is wisely re-designed.

Patience, persistence and a time-series chart are all that is needed. It takes less than a minute per day to monitor the improvement.

Even I can afford to invest a minute per day.

The BaseLine© chart clearly shows that the day-to-day variation is quite high: and that is expected – it is inherent in the 2-out-of-7 Lo-CHO design. It is the not the short-term change that is the measure of success – it is the long-term improvement that is important.

It is important to measure daily – because it is the daily habit that keeps me mindful, aligned, and on-goal. It is not the measurement itself that is the most important thing – it is the conscious act of measuring and then plotting the dot in the context of the previous dots. The picture tells the story. No further “statistical” analysis is required.

The power of this chart is that it provides hard evidence that is very effective for nudging other skeptics like me into giving the innovative idea a try. I know because I have done that many times now. I have converted other skeptics. It is an innovation infection.

And the same principle appears to apply to other areas. What is critical to success is tangible and visible proof of progress. That is what skeptics need. Then a rational and logical method and explanation that respects their individual opinion and requirements. The design has to work for them. And it must make sense.

They will come out with a string of “Yes … buts” and that is OK because that is how skeptics work. Just answer their questions with evidence and explanations. It can get a bit wearing I admit but it is worth the effort.

An effective Improvement Scientist needs to be a healthy skeptic too – i.e. an open minded one.