Stop Press: For those who prefer cartoons to books please skip to the end to watch the Who Moved My Cheese video first.

In 1962 – that is half a century ago – a controversial book was published. The title was “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions” and the author was Thomas S Kuhn (1922-1996) a physicist and historian at Harvard University. The book ushered in the concept of a ‘paradigm shift’ and it upset a lot a people.

In 1962 – that is half a century ago – a controversial book was published. The title was “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions” and the author was Thomas S Kuhn (1922-1996) a physicist and historian at Harvard University. The book ushered in the concept of a ‘paradigm shift’ and it upset a lot a people.

In particular it upset a lot of scientists because it suggested that the growth of knowledge and understanding is not smooth – it is jerky. And Kuhn showed that the scientists were causing the jerking.

Kuhn described the process of scientific progress as having three phases: pre-science, normal science and revolutionary science. Most of the work scientists do is normal science which means exploring, consolidating, and applying the current paradigm. The current conceptual model of how things work. Anyone who argues against the paradigm is regarded as ‘mistaken’ because the paradigm represents the ‘truth’. Kuhn draws on the history of science for his evidence, quoting examples of how innovators such as Galileo, Copernicus, Newton, Einstein and Hawking radically changed the way that we now view the Universe. But their different models were not accepted immediately and ethusiastically because they challenged the status quo. Galileo was under house arrest for much of his life because his ‘heretical’ writings challenged the Church.

Each revolution in thinking was both disruptive and at the same time constructive because it opened a door to allow rapid expansion of knowledge and understanding. And that foundation of knowledge that has been built over the centuries is one that we all take for granted. It is a fragile foundation though. It could be all lost and forgotten in one generation because none of us are born with this knowledge and understanding. It is not obvious. We all have to learn it. Even scientists.

Kuhn’s book was controversial because it suggested that scientists spend most of their time blocking change. This is not necessarily a bad thing. Stability for a while is very useful and the output of normal science is mostly positive. For example the revolution in thinking introduced by Isaac Newton (1643-1727) led directly to the Industrial Revolution and to far-reaching advances in every sphere of human knowledge. Most of modern engineering is built on Newtonian mechanics and it is only at the scales of the very large, the very small and the very quick that it falls over. Relativistic and quantum physics are more recent and very profound shifts in thinking and they have given us the digital computer and the information revolution. This blog is a manifestation of the quantum paradigm.

Kuhn concluded that the progess of change is jerky because scientists create resistance to change to create stability while doing normal science experiments. But these same experiments produce evidence that suggest that the current paradigm is flawed. Over time the pressure of conflicting evidence accumulates, disharmony builds, conflict is inevitable and intellectual battle lines are drawn. The deeper and more fundamental the flaw the more bitter the battle.

In contrast, newcomers seek harmony in the cacophony and propose new theories that explain both the old and the new. New paradigms. The stage is now set for a drama and the public watch bemused as the academic heavyweights slug it out. Eventually a tipping point is reached and one of the new paradigms becomes dominant. Often the transition is triggered by one crucial experiment.

There is a sudden release of the tension and a painful and disruptive conceptual lurch – a paradigm shift. Then the whole process starts over again. The creators of the new paradigm become the consolidators and in time the defenders and eventually the dogmatics! And it can take decades and even generations for the transition to be completed.

It is said that Albert Einstein (1879-1955) never fully accepted quantum physics even though his work planted the seeds for it and experience showed that it explained the experimental observations better. [For more about Einstein click here].

The message that some take from Kuhn’s book is that paradigm shifts are the only way that knowledge can advance. With this assumption getting change to happen requires creating a crisis – a burning platform. Unfortunatelty this is an error of logic – it is a unverified generalisation from an observed specific. The evidence is growing that this we-always-need-a-burning-platform assumption is incorrect. It appears that the growth of knowledge and understanding can be smoother, less damaging and more effective without creating a crisis.

So what is the evidence that this is possible?

Well, what pattern would you look for to illustrate that it is possible to improve smoothly and continually? A smooth growth curve of some sort? Yes – but it is more than that. It is a smooth curve that is steeper than anyone else’s and one that is growing steeper over time. Evidence that someone is learning to improve faster than their peers – and learning painlessly and continuously without crises; not painfully and intermittently using crises.

Two examples are Toyota and Apple.

Toyota is a Japanese car manufacturer that has out-performed other car manufacturers consistently for 40 years – despite the global economic boom-bust cycles. What is their secret formula for their success?

Toyota is a Japanese car manufacturer that has out-performed other car manufacturers consistently for 40 years – despite the global economic boom-bust cycles. What is their secret formula for their success?

We need a bit of history. In the 1980’s a crisis-of-confidence hit the US economy. It was suddenly threatened by higher-quality and lower-cost imported Japanese products – for example cars.

We need a bit of history. In the 1980’s a crisis-of-confidence hit the US economy. It was suddenly threatened by higher-quality and lower-cost imported Japanese products – for example cars.

The switch to buying Japanese cars had been triggered by the Oil Crisis of 1973 when the cost of crude oil quadrupled almost overnight – triggering a rush for smaller, less fuel hungry vehicles. This is exactly what Toyota was offering.

This crisis was also a rude awakening for the US to the existence of a significant economic threat from their former adversary. It was even more shocking to learn that W Edwards Deming, an American statistician, had sown the seed of Japan’s success thirty years earlier and that Toyota had taken much of its inspiration from Henry Ford. The knee-jerk reaction of the automotive industry academics was to copy how Toyota was doing it, the Toyota Production System (TPS) and from that the school of Lean Tinkering was born.

This knowledge transplant has been both slow and painful and although learning to use the Lean Toolbox has improved Western manufacturing productivity and given us all more reliable, cheaper-to-run cars – no other company has been able to match the continued success of Japan. And the reason is that the automotive industry academics did not copy the paradigm – the intangible, subjective, unspoken mental model that created the context for success. They just copied the tangible manifestation of that paradigm. The tools. That is just cynically copying information and knowledge to gain a competitive advantage – it is not respecfully growing understanding and wisdom to reach a collaborative vision.

Apple is now one of the largest companies in the world and it has become so because Steve Jobs (1955-2011), its Californian, technophilic, Zen Bhuddist, entrepreneurial co-founder, had a very clear vision: To design products for people. And to do that they continually challenged their own and their customers paradigms. Design is a logical-rational exercise. It is the deliberate use of explicit knowledge to create something that delivers what is needed but in a different way. Higher quality and lower cost. It is normal science.

Apple is now one of the largest companies in the world and it has become so because Steve Jobs (1955-2011), its Californian, technophilic, Zen Bhuddist, entrepreneurial co-founder, had a very clear vision: To design products for people. And to do that they continually challenged their own and their customers paradigms. Design is a logical-rational exercise. It is the deliberate use of explicit knowledge to create something that delivers what is needed but in a different way. Higher quality and lower cost. It is normal science.

Continually challenging our current paradigm is not normal science. It is revolutionary science. It is deliberately disruptive innovation. But continually challenging the current paradigm is uncomfortable for many and, by all accounts, Steve Jobs was not an easy person to work for because he was future-looking and demanded perfection in the present. But the success of this paradigm is a matter of fact:

“In its fiscal year ending in September 2011, Apple Inc. hit new heights financially with $108 billion in revenues (increased significantly from $65 billion in 2010) and nearly $82 billion in cash reserves. Apple achieved these results while losing market share in certain product categories. On August 20, 2012 Apple closed at a record share price of $665.15 with 936,596,000 outstanding shares it had a market capitalization of $622.98 billion. This is the highest nominal market capitalization ever reached by a publicly traded company and surpasses a record set by Microsoft in 1999.”

And remember – Apple almost went bust. Steve Jobs had been ousted from the company he co-founded in a boardroom coup in 1985. After he left Apple floundered and Steve Jobs proved it was his paradigm that was the essential ingredient by setting up NeXT computers and then Pixar. Apple’s fortunes only recovered after 1998 when Steve Jobs was invited back. The rest is history so click to see and hear Steve Jobs describing the Apple paradigm.

So the evidence states that Toyota and Apple are doing something very different from the rest of the pack and it is not just very good product design. They are continually updating their knowledge and understanding – and they are doing this using a very different paradigm. They are continually challenging themselves to learn. To illustrate how they do it – here is a list of the five principles that underpin Toyota’s approach:

- Challenge

- Improvement

- Go and see

- Teamwork

- Respect

This is Win-Win-Win thinking. This is the Science of Improvement. This is Improvementology®.

So what is the reason that this proven paradigm seems so difficult to replicate? It sounds easy enough in theory! Why is it not so simple to put into practice?

The requirements are clearly listed: Respect for people (challenge). Respect for learning (improvement). Respect for reality (go and see). Respect for systems (teamwork).

In a word – Respect.

Respect is a big challenge for the individualist mindset which is fundamentally disrespectful of others. The individualist mindset underpins the I-Win-You-Lose Paradigm; the Zero-Sum -Game Paradigm; the Either-Or Paradigm; the Linear-Thinking Paradigm; the Whole-Is-The-Sum-Of-The-Parts Paradigm; the Optimise-The-Parts-To-Optimise-The-Whole Paradigm.

Unfortunately these are the current management paradigms in much of the private and public worlds and the evidence is accumulating that this paradigm is failing. It may have been adequate when times were better, but it is inadequate for our current needs and inappropriate for our future needs.

So how can we avoid having to set fire to the current failing management paradigm to force a leap into the cold and uninviting reality of impending global economic failure? How can we harness our burning desire for survival, security and stability? How can we evolve our paradigm pro-actively and safely rather than re-actively and dangerously?

We need something tangible to hold on to that will keep us from drowning while the old I-am-OK-You-are-Not-OK Paradigm is dissolved and re-designed. Like the body of the caterpillar that is dissolved and re-assembled inside the pupa as the body of a completely different thing – a butterfly.

We need something tangible to hold on to that will keep us from drowning while the old I-am-OK-You-are-Not-OK Paradigm is dissolved and re-designed. Like the body of the caterpillar that is dissolved and re-assembled inside the pupa as the body of a completely different thing – a butterfly.

We need a robust and resilient structure that will keep us safe in the transition from old to new and we also need something stable that we can steer to a secure haven on a distant shore.

We need a conceptual lifeboat. Not just some driftwood, a bag of second-hand tools and no instructions! And we need that lifeboat now.

But why the urgency?

The answer is basic economics.

The answer is basic economics.

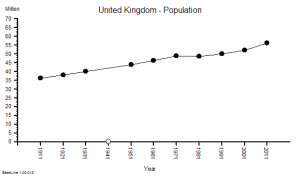

The UK population is growing and the proportion of people over 65 years old is growing faster. Advances in healthcare means that more of us survive age-related illnesses such as cancer and heart disease. We live longer and with better quality of life – which is great.

But this silver-lining hides a darker cloud.

The proportion of elderly and very elderly will increase over the next 20 years as the post WWII baby-boom reaches retirement age. The number of people who are living on pensions is increasing and the demands on health and social services is increasing. Pensions and public services are not paid out of past savings they are paid out of current earnings. So the country will need to earn more to pay the bills. The UK economy will need to grow.

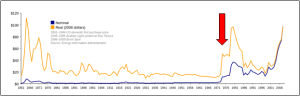

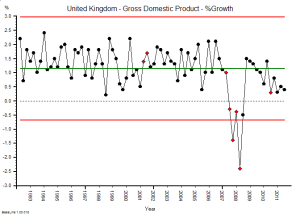

But the UK economy is not growing. Our Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is currently about £380 billion and flat as a pancake. This sounds like a lot of dosh – but when shared out across the population of 56 million it gives a more modest figure of just over £100 per person per week. And the time-series chart for the last 20 years shows that the past growth of about 1% per quarter took a big dive in 2008 and went negative! That means serious recession. It recovered briefly but is now sagging towards zero.

But the UK economy is not growing. Our Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is currently about £380 billion and flat as a pancake. This sounds like a lot of dosh – but when shared out across the population of 56 million it gives a more modest figure of just over £100 per person per week. And the time-series chart for the last 20 years shows that the past growth of about 1% per quarter took a big dive in 2008 and went negative! That means serious recession. It recovered briefly but is now sagging towards zero.

So we are heading for a big economic crunch and hiding our heads in the sand and hoping for the best is not a rational strategy. The only way to survive is to cut public services or for tax-funded services to become more productive. And more productive means increasing the volume of goods and services for the same cost. These are the services that we will need to support the growing population of dependents but without increasing the cost to the country – which means the taxpayer.

The success of Toyota and Apple stemmed from learning how to do just that: how to design and deliver what is needed; and how to eliminate what is not; and how to wisely re-invest the released cash. The difference can translate into higher profit, or into growth, or into more productivity. It just depends on the context. Toyota and Apple went for profit and growth. Tax-funded public services will need to opt for productivity.

And the learning-productivity-improvement-by-design paradigm will be a critical-to-survival factor in tax-payer funded public services such as the NHS and Social Care. We do not have a choice if we want to maintain what we take for granted now. We have to proactively evolve our out-of-date public sector management paradigm. We have to evolve it into one that can support dramatic growth in productivity without sacrificing quality and safety.

We cannot use the burning platform approach. And we have to act with urgency.

We need a lifeboat!

Our current public sector management paradigm is sinking fast and is being defended and propped up by the old school managers who were brought up in it. Unfortunately the evidence of 500 years of change says that the old school cannot unlearn. Their mental models go too deep. The captains and their crews will go down with their ships. [Remember the Titanic the unsinkable ship that sank in 1912 on the maiden voyage. That was a victory of reality over rhetoric.]

Those of us who want to survive are the ‘rats’. We know when it is time to leave the sinking ship. We know we need lifeboats because it could be a long swim! We do not want to freeze and drown during the transition to the new paradigm.

So where are the lifeboats?

One possibility is an unfamiliar looking boat called “6M Design”. This boat looks odd when viewed through the lens of the conventional management paradigm because it combines three apparently contradictiry things: the rational-logical elements of system design; the respect-for-people and learning-through-challenge principles embodied by Toyota and Apple; and the counter-intuitive technique of systems thinking.

Another reason it feel odd is because “6M Design” is not a solution; it is a meta-solution. 6M Design is a way of creating a good-enough-for-now solution by changing the current paradigm a bit at a time. It is a-how-to-design framework; it is not the-what-to-do solution. 6M Design is a paradigm shaper – not a paradigm shaker or a paradigm shifter.

And there is yet another reason why 6M Design does not float the current management boat. It does not need to be controlled by self-appointed experts. Business schools and management consultants, who have a vested interest in defending the current management paradigm, cannot make a quick buck from it because they are irrelevant. 6M Design is intended to be used by anyone and everyone as a common language for collectively engaging in respectful challenge and lifelong learning. Anyone can learn to use it. Anyone.

We do not need a crisis to change. But without changing we will get the crisis we do not want. If we choose to change then we can choose a safer and smoother path of change.

The choice seems clear. Do you want to go down with the ship or stay afloat aboard an innovation boat?

And we will need something to help us navigate our boat.

If you are a reflective, conceptual learner then you might ike to read a synopsis of Thomas Kuhn’s book. You can download a copy here. [There is also a 50 year anniversary edition of the original that was published this year].

And if you prefer learning from stories then there is an excellent one called “Who Moved My Cheese” that describes the same challenge of change. And with the power of the digital paradigm you can watch the video here.