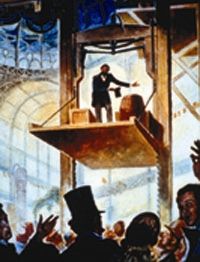

The picture is of Elisha Graves Otis demonstrating, in the mid 19th century, his safe elevator that automatically applies a brake if the lift cable breaks. It is a “simple” fail-safe mechanical design that effectively created the elevator industry and the opportunity of high-rise buildings.

The picture is of Elisha Graves Otis demonstrating, in the mid 19th century, his safe elevator that automatically applies a brake if the lift cable breaks. It is a “simple” fail-safe mechanical design that effectively created the elevator industry and the opportunity of high-rise buildings.

“To err is human” and human factors research into how we err has revealed two parts – the Error of Intention (poor decision) and the Error of Execution (poor delivery) – often referred to as “mistakes” and “slips”.

Most of the time we act unconsciously using well practiced skills that work because most of our tasks are predictable; walking, driving a car etc.

The caveman wetware between our ears has evolved to delegate this uninteresting and predictable work to different parts of the sub-conscious brain and this design frees us to concentrate our conscious attention on other things.

So, if something happens that is unexpected we may not be aware of it and we may make a slip without noticing. This is one way that process variation can lead to low quality – and these are the often the most insidious slips because they go unnoticed.

It is these unintended errors that we need to eliminate using safe process design.

There are two ways – by designing processes to reduce the opportunity for mistakes (i.e. improve our decision making); and then to avoid slips by designing the subsequent process to be predictable and therefore suitable for delegation.

Finally, we need to add a mechanism to automatically alert us of any slips and to protect us from their consequences by failing-safe. The sign of good process design is that it becomes invisible – we are not aware of it because it works at the sub-conscious level.

As soon as we become aware of the design we have either made a slip – or the design is poor.

Suppose we walk up to a door and we are faced with a flat metal plate – this “says” to us that we need to “push” the door to open it – it is unambiguous design and we do not need to invoke consciousness to make a push-or-pull decision. The technical term for this is an “affordance”.

In contrast a door handle is an ambiguous design – it may require a push or a pull – and we either need to look for other clues or conduct a suck-it-and-see experiment. Either way we need to switch our conscious attention to the task – which means we have to switch it away from something else. It is those conscious interruptions that cause us irritation and can spawn other, possibly much bigger, slips and mistakes.

Safe systems require safe processes – and safe processes mean fewer mistakes and fewer slips. We can reduce slips through good design and relentless improvement.

A simple and effective tool for this is The 4N Chart® – specifically the “niggle” quadrant.

Whenever we are interrupted by a poorly designed process we experience a niggle – and by recording what, where and when those niggles occur we can quickly focus our consciousness on the opportunity for improvement. One requirement to do this is the expectation and the discipline to record niggles – not necessarily to fix them immediately – but just to record them and to review them later.

In his book “Chasing the Rabbit” Steven Spear describes two examples of world class safety: the US Nuclear Submarine Programme and Alcoa, an aluminium producer. Both are potentially dangerous activities and, in both examples, their world class safety record came from setting the expectation that all niggles are recorded and acted upon – using a simple, effective and efficient niggle-busting process.

In stark and worrying contrast, high-volume high-risk activities such as health care remain unsafe not because there is no incident reporting process – but because the design of the report-and-review process is both ineffective and inefficient and so is not used.

The risk of avoidable death in a modern hospital is quoted at around 1:300 – if our risk of dying in an elevator were that high we would take the stairs! This worrying statistic is to be expected though – because if we lack the organisational capability to design a safe health care delivery process then we will lack the organisational capability to design a safe improvement process too.

Our skill gap is clear – we need to learn how to improve process safety-by-design.

Download Design for Patient Safety report written by the Design Council.

Other good examples are the WHO Safer Surgery Checklist, and the story behind this is told in Dr Atul Gawande’s Checklist Manifesto.