There are two directions from which we can approach an improvement challenge. From the bottom up – starting with the real details and distilling the principle later; and from the top down – starting with the conceptual principle and doing the detail later. Neither is better than the other – both are needed.

There are two directions from which we can approach an improvement challenge. From the bottom up – starting with the real details and distilling the principle later; and from the top down – starting with the conceptual principle and doing the detail later. Neither is better than the other – both are needed.

As individuals we have an innate preference for real detail or conceptual principle – and our preference is manifest by the way we think, talk and behave – it is part of our personality. It is useful to have insight into our own personality and to recognise that when other people approach a problem in a different way then we may experience a difference of opinion, a conflict of styles, and possibly arguments.

One very well established model of personality type was proposed by Carl Gustav Jung who was a psychologist and who approached the subject from the perspective of understanding psychological “illness”. Jung’s “Psychological Types” was used as the foundation of the life-work of Isabel Briggs Myers who was not a psychologist and who was looking from the direction of understanding psychological “normality”. In her book Gifts Differing – Understanding Personality Type (ISBN 978-0891-060741) she demonstrates using empirical data that there is not one normal or ideal type that we are all deviate from – rather that there is a set of stable types that each represents a “different gift”. By this she means that different personality types are suited to different tasks and when the type resonantes with the task it results in high-performance and is seen an asset or “strength” and when it does not it results in low performance and is seen as a liability or “weakness”.

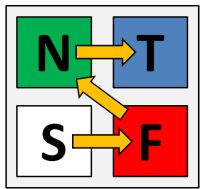

One of the multiple dimensions of the Jungian and Myers-Briggs personality type model is the Sensor – iNtuitor dimension the S-N dimension. This dimension represents where we hold our reference model that provides us with data – data that we convert to information – and informationa the we use to derive decisions and actions.

A person who is naturally inclined to the Sensor end of the S-N dimension prefers to use Reality and Actuality as their reference – and they access it via their senses – sight, sound, touch, smell and taste. They are often detail and data focussed; they trust their senses and their conscious awareness; and they are more comfortable with routine and structure.

A person who is naturally inclined to the iNtuitor end of the S-N dimension prefers to use Rhetoric and Possibility as their reference and their internal conceptual model that they access via their intuition. They are often principle and concept focussed and discount what their senses tell them in favour their intuition. Intuitors feel uncomfortable with routine and structure which they see as barriers to improvement.

So when a Sensor and an iNtuitor are working together to solve a problem they are approaching it from two different directions and even when they have a common purpose, common values and a common objective it is very likely that conflict will occur if they are unaware of their different gifts.

Gaining this awareness is a key to success because the synergy of the two approaches is greater than either working alone – the sum is greater than the parts – but only if there is awareness and mutual respect for the different gifts. If there is no awareness and low mutual respect then the sum will be less than the parts and the problem will not be dissolvable.

In her research, Isabel Briggs Myers found that about 60% of high school students have a preference for S and 40% have a preference for N – but when the “academic high flyers” were surveyed the ratio was S=17% and N=83% – and there was no difference between males and females. When she looked at the S-N distribution in different training courses she discovered that there were a higher proportion of S-types in Administrators (59%), Police (80%), and Finance (72%) and a higher proportion of N-types in Liberal Arts (59%), Engineering (65%), Science (83%), Fine Arts (91%), Occupational Therapy (66%), Art Education (87%), Counselor Education (85%), and Law (59%). Her observation suggested that individuals select subjects based on their “different gifts” and this throws an interesting light on why traditional professions may come into conflict and perhaps why large organisations tend to form departments of “like-minded individuals”. Departments with names like Finance, Operations and Governance – or FOG.

This insight also offers an explanation for the conflict between “strategists” who tend to be N-types and who naturally gravitate to the “manager” part of an organisation and the “tacticians” who tend to be S-types and who naturally gravitate to the “worker” part of the same organisation.

It has also been shown that conventional “intelligence tests” favour the N-types over the S-types and suggests why highly intelligent academics my perform very poorly when asked to apply their concepts and principles in the real world. Effective action requires pragmatists – but academics tend to congregate in academic instituitions – often disrespectfully labelled by pragmatists as “Ivory Towers”.

Unfortunately this innate tendency to seek-like-types is counter-productive because it re-inforces the differences, exacerbates the communication barriers, and leads to “tribal” and “disrespectful” and “trust eroding” behaviour, and to the “organisational silos” that are often evident.

Complex real-world problems cannot be solved this way because they require the synergy of the gifts – each part playing to its strength when the time is right.

The first step to know-how is self-awareness.

If you would like to know your Jungian/MBTI® type you can do so by getting the app: HERE