One of the foundations of Improvement Science is visualisation – presenting data in a visual format that we find easy to assimilate quickly – as pictures.

We derive deeper understanding from observing how things are changing over time – that is the reality of our everyday experience.

And we gain even deeper understanding of how the world behaves by acting on it and observing the effect of our actions. This is how we all learned-by-doing from day-one. Most of what we know about people, processes and systems we learned long before we went to school.

When I was at school the educational diet was dominated by rote learning of historical facts and tried-and-tested recipes for solving tame problems. It was all OK – but it did not teach me anything about how to improve – that was left to me.

More significantly it taught me more about how not to improve – it taught me that the delivered dogma was not to be questioned. Questions that challenged my older-and-better teachers’ understanding of the world were definitely not welcome.

Young children ask “why?” a lot – but as we get older we stop asking that question – not because we have had our questions answered but because we get the unhelpful answer “just because.”

When we stop asking ourselves “why?” then we stop learning, we close the door to improvement of our understanding, and we close the door to new wisdom.

So to open the door again let us leverage our inborn ability to gain understanding from interacting with the world and observing the effect using moving pictures.

Unfortunately our biology limits us to our immediate space-and-time, so to broaden our scope we need to have a way of projecting a bigger space-scale and longer time-scale into the constraints imposed by the caveman wetware between our ears.

Something like a video game that is realistic enough to teach us something about the real world.

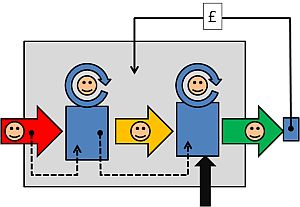

If we want to understand better how a health care system behaves so that we can make wiser decisions of what to do (and what not to do) to improve it then a real-time, interactive, healthcare system video game might be a useful tool.

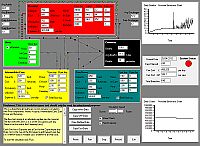

So, with this design specification I have created one.

The goal of the game is to defeat the enemy – and the enemy is intangible – it is the dark cloak of ignorance – literally “not knowing”.

Not knowing how to improve; not knowing how to ask the “why?” question in a respectful way. A way that consolidates what we understand and challenges what we do not.

And there is an example of the Health Care System Flow Game being played here.